Import Imperatives

How and why middle powers should import frontier AI systems

Together with Sam Winter-Levy, Liam Patell and Sarosh Nagar, I recently published a report for the Foundation of American Innovation: ‘An Allied World on the American AI Stack’, describing how the U.S. might mount a program to promote the export of AI to its allies.

The following post outlines my motivation for that work and looks at the other side of the same coin, describing why and how middle powers should approach U.S. AI exports.

The issue of technological sovereignty is back on the agenda for many of the world’s major economies. A moment of geopolitical realignment is coinciding with an unfortunate timing in technology history—a moment dominated by the rise of advanced AI, a technology that looks superficially similar to past waves of digital products, but comes with drastically different infrastructural premises and therefore strategic conclusions. In the context of this argument, I and many others have argued that middle powers should attempt leverage-based plays, strengthen their negotiating positions, and so on. In this piece, I want to go into some more detail on one of the more technical links of this argument: how a framework for importing AI might be justified and executed.

The path toward this sovereignty in the age of AI is thin, with chasms on both sides. To the left, there’s the risk of not taking frontier AI seriously—to think that surely, you’ll find the AI someplace, and that it would be ubiquitous as the result of usual innovation dynamics. That will leave you scrambling for AI access, however coercive, at the eleventh hour. To the right, there’s the risk of misunderstanding what it means to take frontier AI seriously—and to think that it means you should build your own models at all costs. That leaves you wasting precious time and resources on a low-margin, winner-takes-all element of the AI stack. In between, there’s realising frontier AI is seriously important, and drawing the correct conclusion: guaranteeing redundant supply to both your government and your economy through a mix of sovereign sub-frontier capabilities and layered, diverse import deals for top-shelf inference.

Middle Powers Need Frontier AI

This all starts with briefly motivating the need for AI imports altogether. There are broadly two classes of arguments on frontier AI access: why in a vacuum, middle powers should seek to maximise the capability of the AI they deploy; and why in comparison, middle powers should be wary of falling behind in the capability of AI they deploy. Both these arguments are shrouded in uncertainty—and I don’t mean to suggest that all future trajectories definitely point toward needing the very best AI for every use case. But I think taken together, the odds are decent that this requirement will arise at least along some of the following dimensions—good enough that it should stop a responsible middle power from foregoing access to frontier AI.

Why You Want Good AI

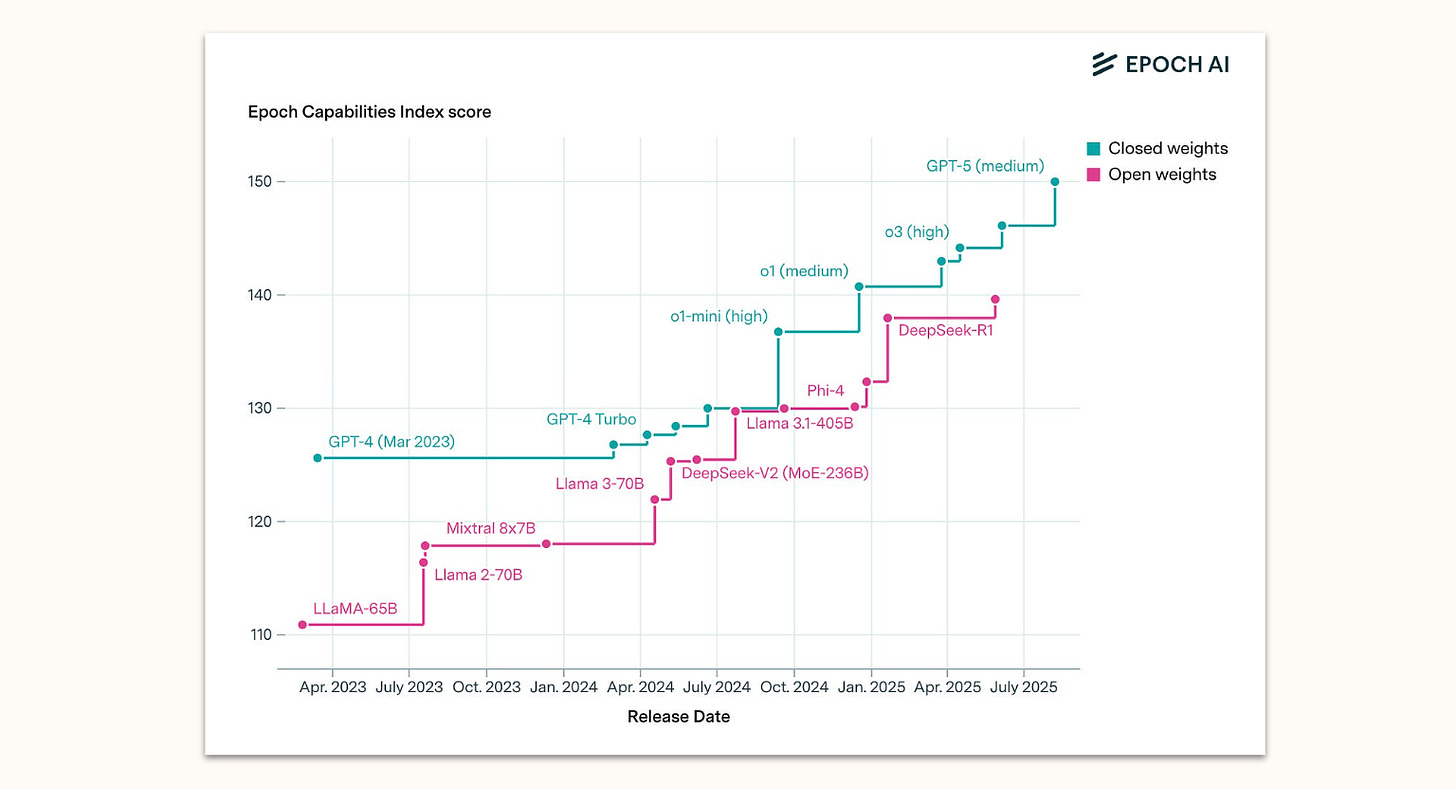

In the interest of keeping this post somewhat focused, I won’t rehash the general case for advanced AI at length. Suffice it to say that AI capabilities are on track to become meaningful drivers of economic growth, strategic capability, and scientific progress. They serve as a force multiplier for existing capacity: accelerating research, compounding productivity gains, and making previously scarce forms of expertise and analysis abundantly available. Governments that deploy advanced AI stand to dramatically improve the quality and reach of public services; firms stand to unlock substantial efficiency gains and new revenue streams; and the scientific enterprise stands to benefit from AI’s ability to accelerate discovery across domains. In a world where these capabilities are rapidly improving and widely deployed, any country that opts out of serious AI adoption is accepting a structural disadvantage across virtually every dimension of national capacity. The baseline intuition, of course, is then that better AI probably makes for better national performance across the board.

Why You Want The Best AI

But if this was only a matter of pushing, relentlessly, the frontier of what AI can help societies achieve, you’d still have reason to object to the frontier-focused logic. Just as much as the best talent outperforms mediocre talent, but it is still not a strategic imperative to pay everyone hundreds of thousands in wages, you might say that your resources aren’t best spent on maximising AI capability. This underestimates the incredibly thin margins of strategic and economic competition that might come with an AI age, and what they mean for what constitutes a minimum viable stack.

A middle power’s AI capabilities need to keep up on three levels of competition:

Economically, firms and workers equipped with inferior AI risk being outcompeted by rivals wielding stronger systems. AI will exacerbate the pace and international nature of market competition, shrinking institutional moats and compressing the margins on which competitive advantage rests. We can already see glimpses of this in environments where competition is most intense: in high-frequency financial trading, microseconds of latency advantage justify enormous infrastructure investment; at the frontier of AI development itself, companies treat even marginal capability differences as competitively decisive. In an AI-saturated economy, these dynamics will extend far beyond niche markets—the capability gap between frontier and near-frontier systems may translate directly into competitive disadvantage for entire national industries.

In terms of government capacity, states need AI capabilities at least comparable to those available elsewhere if they are to provide for their citizens at a competitive standard. But the sharper version of this point is that a government not adequately equipped with advanced AI runs the risk of being overwhelmed by the sheer volume and sophistication of AI-generated activity it must process and regulate—AI-assisted regulatory filings, legal challenges, synthetic media and automated public communications. Without matching capabilities, the administrative state risks being structurally outpaced by actors it is meant to govern.

In terms of security, having AI as good as your adversaries’ is a precondition for effective national defence. Attackers—foreign states, non-state actors, criminal networks—will be equipped with near-leading AI capabilities through stolen models, jailbreaks, or near-frontier open-source systems. They will use these to devise and execute cyberattacks, develop chemical and biological weapons, and serve as a force multiplier for hostile operations. The offence-defence balance in AI remains uncertain, but research consistently finds that more advanced models are more effective on both sides of the equation. A country wielding weaker AI than its adversaries is accepting a security deficit it cannot afford. To many researchers in the field, it’s plausible that this balance will remain on a knife’s edge—the question of whether a middle power wins its game of whack-a-mole against the quickly accelerating onslaught of AI-driven attacks might have a lot to do with the capabilities middle powers can deploy.

Middle Powers Can’t Build Frontier AI

The core mistake in middle power strategy today is to realise this importance of frontier AI, but take away from it an interest in building their own AI systems. Once the mistaken assumptions behind this impulse are clarified, the precise requirements for import deals become clear.

You Don’t Have The Cards

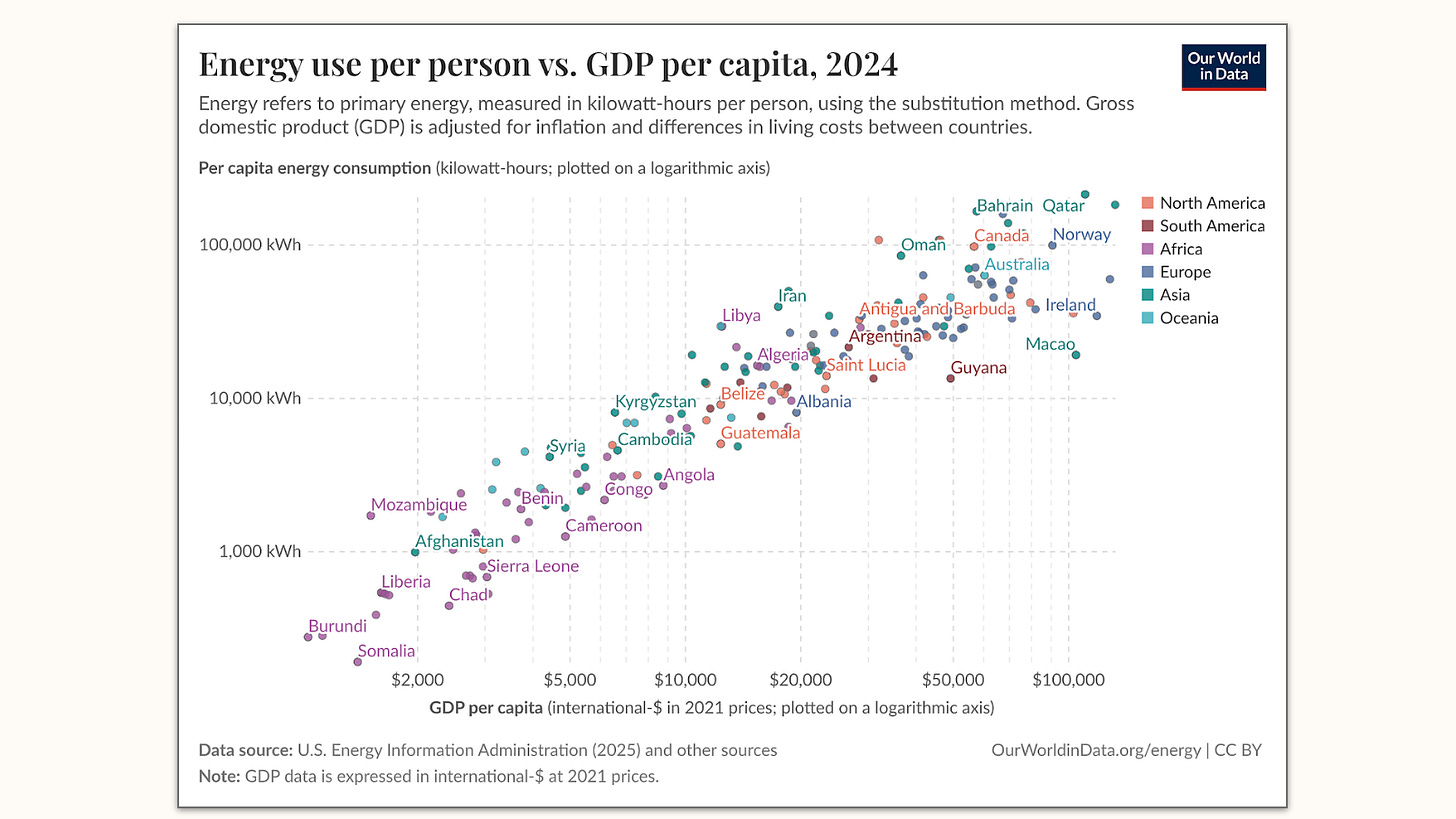

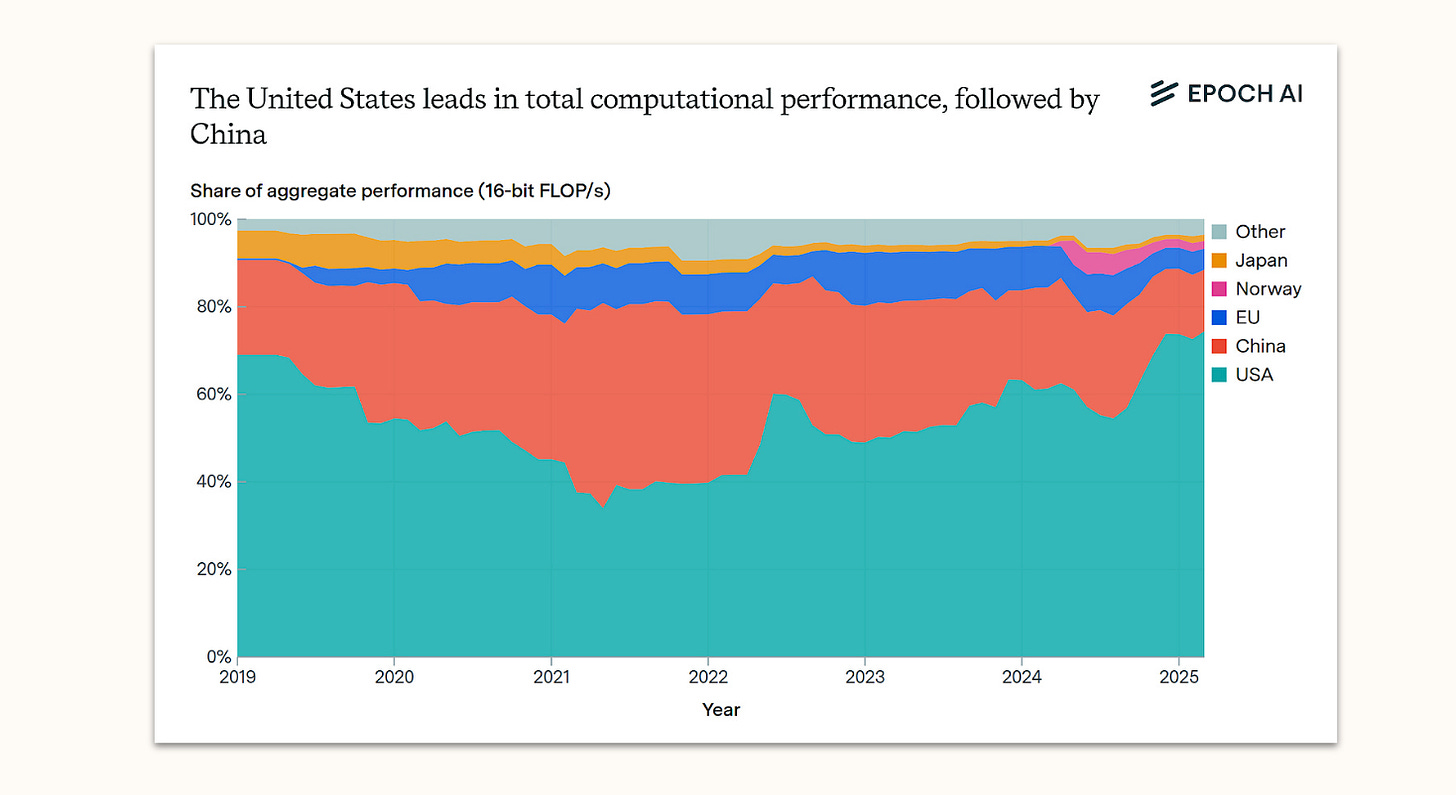

Once again, middle powers are exceedingly unlikely to develop their own frontier AI systems. I don’t want to derail this piece too far by repeating this well-developed point, so to summarise in brief terms: The key inputs for frontier development are capital, energy, chips, talent—and indirectly, the ability to eventually turn software innovation into revenue that can fuel a revenue flywheel. Any place in the world other than the US and China is outmatched along these lines already. But more to the point, the contours of the infrastructure race tomorrow are not shaped by today’s scramble to catch up, but by yesterday’s buildout decisions. The infrastructure that has built current American leadership in AI is negligible compared to the clusters that will come online this year—gigawatts of computational capacity, orders of magnitude greater than what we had in 2024. The most ambitious middle power projects promise a catch-up to America’s capacity as it was last year. But the moving target they are chasing keeps accelerating, and even the articulated ambitions from elsewhere have not kept pace.

The most persistent hope to reach the frontier runs through the notion of finding a shortcut past the infrastructure competition—perhaps a new paradigm that sidesteps the need for massive compute. I and others have argued at length why this is unlikely to work: paradigm search itself benefits from scale; whatever new approach emerges will almost certainly require substantial infrastructure to become strategically meaningful; and the major labs, far from being locked into a single bet, have introduced novel paradigms repeatedly while maintaining their lead. The scaling challenge is the one middle powers have consistently failed to solve, and there is little reason to think a government-backed initiative will break that pattern.

The Peril of Sub-Frontier Champions

What middle powers can do, of course, is develop AI that’s just fine. This is, in effect, the business model of national champions like Mistral, Cohere, and so on. They can—and effectively often do—pursue a strategy of ‘fast following’: finding efficient ways to replicate the most successful approaches taken at the frontier, staying cost-efficient at doing so through a mixture of genuine innovation, quick replication, and shameless distillation.

It’s not quite clear to me if this will remain viable forever: if you assume the costs of fast-following stay stable at some percentage of frontier development, but think that revenue accrues mostly with developers at the very frontier, it follows that fast followers will burn through increasing amounts of cash without the solace of the kinds of massive revenue prospects that major developers enjoy. But even provided you can find some way to make a fast-following so-called frontier ambition cash neutral, misunderstanding their value can jeopardise any broader national AI strategy.

Today, some middle powers have realised the first part of my argument, but haven’t quite understood that their local frontier ambitions are likely to utterly fail. This is perhaps the most dangerous position to be in, because it fails extraordinarily slowly and binds political capital and financial resources on the way. If you simply don’t get that AI is happening, and reality blows up in your face, you can still at least try to pivot dramatically. But if you think that yes, AI is big, but you just invested a couple hundred million into a frontier AI initiative, and they’re telling you things are going great, you might be tempted to wait another few months, another year or two. It would be politically costly to admit the initial funding had been wasted, read as a lack of support to your local innovators, and so on. Whenever an external shock prompts you to think ‘maybe you should do something’, you’ll respond with ‘ah, don’t worry, our frontier AI initiative is working on it’---and by the time it has burned through all your money, it’ll be too late.

Banking too much on the illusion of solving the problem through fast-following also carries economic and strategic risks because it creates political incentives for middle powers to force their economies and institutions to use sub-par solutions. You can see inklings of this in past conversations on digital sovereignty (and in France): to protect their nascent or subpar alternatives, middle powers create regulatory constraints that forcibly create a steady demand signal. They’ll apply burdensome regulation to foreign alternatives, give tax privileges for using domestic solutions, or focus government procurement on national champions. Currently, this mostly means that French civil servants have to start every meeting by spending five minutes logging into a bastardisation of Zoom that doesn’t work before jumping on a phone call instead. It’s a little bit less funny if it means that businesses and institutions experience the marked competitive disadvantages I describe above because the government wants to incubate national champions that’ll never go anywhere.

Insofar as you think subfrontier champions are viable and you want to pursue them as a middle power, you need to do your absolute best to resist the political reflex to protect them at all costs. They are precisely and only valuable if they do not distort your decision-making, do not hijack your broader AI strategies. Give them limited, non-discriminatory support that doesn’t trade off against imports, see whether fast-following actually stays viable without being a cash sink, and only keep doing it if that’s true. Above all, you cannot give in to the tempting illusion that these sub-frontier champions are on a path toward the frontier, or they’ll cloud your judgement for navigating important import deals. National champions can only ever be a small part of middle powers’ AI strategies; and frontier AI they do not provide.

Middle Powers Can Get Frontier AI

So, middle powers should import frontier AI. But that’s easier said than done. The current import mix, by volume of tokens provided, is massively dominated by three categories: import through the use of foreign-developed open-source models; through API calls to foreign developers; and through simple consumer-level subscriptions. None of these are a reliable channel for importing a strategically important input.

Against Naive Import Structures

Scaffolding around open-source models fundamentally assumes the continued deployment of highly capable OS models. This is already not really given today: open-source models are fine, but usually a generation behind the actual frontier. Attractors pull both ways: the U.S. administration would like domestic developers to deploy good open source models to eat into Chinese market share in that area, but it’s really hard to make revenue targets when you open source actually impressive capabilities, and serious misuse concerns still remain unanswered. Perhaps China does not care, and aggressively open-sources highly capable models to undercut U.S. market share—but who’s to say they’ll keep doing so once middle powers have gotten hooked on the prospect of Chinese open source, and who knows about the much-discussed security implications? Open source is far from a reliable pathway to accessing frontier capabilities.

API and consumer-level access alone are obviously not a serious sovereign channel for securing access to a strategically relevant resource: the precise conditions for access are usually not enforceable, there is little leeway for negotiating and actually enforcing treatment of privileged data, little guarantee to migrate workflows and requirements from one developer to the other, and so on. In the AI developers’ standard business offerings, the terms are set by volatile young companies still searching for their exact product portfolios, preferred markets, and so on—companies that still routinely experiment with their pricing, the suite of available models, etc.

If access to frontier AI as provided by foreign developers is to be reliable enough to assuage middle powers’ sovereignty concerns, it can’t be principally provided through a channel this volatile. That’s not to say firms and consumers wouldn’t ultimately access AI capabilities through APIs and subscriptions—it’s just to say that the provision of these capabilities should flow through a higher layer of longer-term national-level framework instead of being strict ad-hoc B2B relationships between middle power firms and US developers.

Imports As Statecraft

What should instead be the shape of AI import deals? For the vast majority of middle powers, I think the most realistic solution is high-level government-backed framework agreements with major developers that provide for (a) directly negotiated capabilities provided to governments and (b) framing, guarantees and conditions for specific agreements between the private sector in middle powers and the developers abroad. These exist today already in the shape of ‘for countries’ deals between AI developers and countries, such as OpenAI’s Stargate initiative; but most Stargates are limited in scope, and not designed to provide AI access at scale for entire national economies. You could combine dedicated Stargate-style projects with broader hyperscaler expansions as well as deals for remote access to foreign-hosted inference to develop a layered stack of AI access options for your public and private sector—perhaps the closest to this has been the UK-US Tech Prosperity Deal, much of which points in exactly the right direction (and has regrettably now stalled).

Some misgivings about this kind of deal have been brought forward by those who have noticed the U.S. government’s increased interest in leveraging technology deals to gain concessions in other areas of foreign policy. This will require a substantial buildup of domestic leverage on the side of middle powers to avoid. Nevertheless, I strongly believe despite all recent geopolitical turmoil, America and not China should be and remain the world’s partner of choice here, even if the Chinese did manage to mount a competitive export program at some point soon. But I recognise that some middle powers will be served well by ‘playing both sides’ and playing off interested importers against each other, so I’ll try to provide a general account of how to structure reliable import deals.

Three Levels of Mechanism

The modalities of contracted AI access a middle power should negotiate for are best understood as corresponding to three levels of importers’ risk. The differences between these risks matter: sovereignty solutions that only dodge the first level are ineffective against more serious dependencies; expensive independent stacks are not required to address minor pricing concerns. When middle powers aim policy at reducing dependencies, they should clarify what level they are addressing.

The first level of risk is getting iteratively gouged—AI exporters as predatory software companies. Rates increase, prices hike, you don’t get the full-powered version of the AI system next year anymore—just like dealing with a slightly inconvenient software vendor. The way around this level of risk is fairly simple—it requires provisions that prevent lock-in into any one vendor. Competition is the antidote to unfair pricing practices, and so middle powers need to ensure a modicum of optionality in their decisions between different imported AI services. You could imagine this to happen on a few different levels: building some optionality into datacenter deals that mean your infrastructure locks you into one provider of models1; and building and procuring independent scaffolding that allows for the exchange of models used in important applications.

The second level of risk is getting your supply pinched—AI exporters as OPEC. In conversations with middle powers, I sometimes hear uncertainty about why any AI exporter would really leverage access. I think this is where the analogy with software licenses obviously stops: to continue to service AI capabilities, a large amount of fundamentally highly fungible computing power is required. That makes it feasible and sometimes attractive to throttle middle power’s access: because infrastructure providers want to exert OPEC-style pressure on pricing to ensure profitability, or because exporters might want to redeploy limited computing capacity to use cases they consider more important than exporting AI to middle powers—large training runs, domestic inference, and so on.

It’s very difficult to avoid this: you can’t stockpile AI capability, so you’re always vulnerable to spot changes, and as we’ve seen with oil, exporters can always feign substantive constraints outside the scope of any contract. A heterogeneous landscape of inference providers for your economy helps here: different countries and developers are developing their respective approaches to servicing inference—out of the Gulf, Norway, local hyperscaler datacenters, joint projects and so on. A wide spread helps avoid pinches from any one constraint. It’s also much easier to avoid this risk if you build out enough domestic compute to ensure inference sovereignty, but there are costly trade-offs involved in this.

The third level of risk is getting cut off—AI exporters as Russia. If push came to shove, AI exporters might simply be able to turn off importers’ access to AI systems altogether. This is, of course, a nuclear option: it destroys both the international credibility of the exporting country and the economic viability of the exporting companies for quite a long time. But in an unstable world order, some middle powers might feel uneasy about an outright cutoff even being a distant option. You cannot dodge this risk entirely—if you run your entire economy on wartime infrastructure that isn’t market-efficient in peacetime—building your own models on your own compute—, you’re going to be broke by the time wartime comes around.

But you can mitigate the worst risks. One way is deploying some genuinely sovereign high-security infrastructure to run national-security-relevant applications, for which you need high-security datacenters as well as appropriate contracts with developers. Another way is keeping a sub-frontier fast follower at least somewhere in your orbit of close and dependable allies that you could fall back to if you actually get cut off—if the existence of a developer like Mistral were a joint fallback for European allies, that might be a path to keep it viable.

Taken together, the measures middle powers need to take to avoid these risks provide a decent outline of the contracts they should seek out—and inversely, the import deals the U.S. government should endorse and the American developers should offer. Ideally, they occur in a financialised market for infrastructure, in a network of independent and complementary contracts with hyperscalers, developers, and nation-states for inference provision, and they all feed into a layer of national scaffolding that is somewhat robust to changes in imported model capability. This export/import framework is mutually beneficial: it would provide America with allies that do not hesitate to buy its technology, and allies with the assurance they can trust their primary source of artificial intelligence.

Outlook

This is quite the wishlist, and it will require middle powers to step up their game in related areas to leverage their way to get at least some of it: as I’ve discussed in the past, they need to aggressively use their positions in upstream and downstream bottlenecks and pursue joint negotiations. But as much as it’s a wishlist, it’s also advice to exporters: if they can’t make middle powers an export offer that feels tenable, middle powers might instead still choose to try their hand at ill-fated sovereignty ambitions. That would hurt middle powers the most, but it still means you lose out on your export sales, too—so it’s in everyone’s interest to scope out how a viable import/export paradigm would look. I’ve written in some detail about the exporter-side considerations on this topic, and I still believe there is substantial overlapping interest here.

But getting the question of frontier AI access right does not solve the question of middle power strategy, and in fact places a greater burden on the resulting strategic questions: especially if you import your frontier AI, you will need to put it to good economic use to make sure you retain the leverage to back up your dealmaking and guarantee the revenue required to finance the inflow of AI. Much more on these questions will follow on this publication in short order. For now, I’ll close by reiterating: as painful as the role of AI importer might be, middle powers cannot avoid it. Their focus must now be on building the best version of an import paradigm.

This raises some interesting questions about the future of ASICs in country-level exports: developers might prefer to export their in-house compute to ensure long-term lock-in, but importers will prefer multi-purpose compute