Forging a Pax Silica

Can the Western alliance be rebuilt on techno-strategical leverage?

The Trump administration is moving to change the underpinnings of American alliances from shared values to mutual technological leverage. If the US can convince its allies to play their part, a narrow path toward a stable global order might still lie ahead.

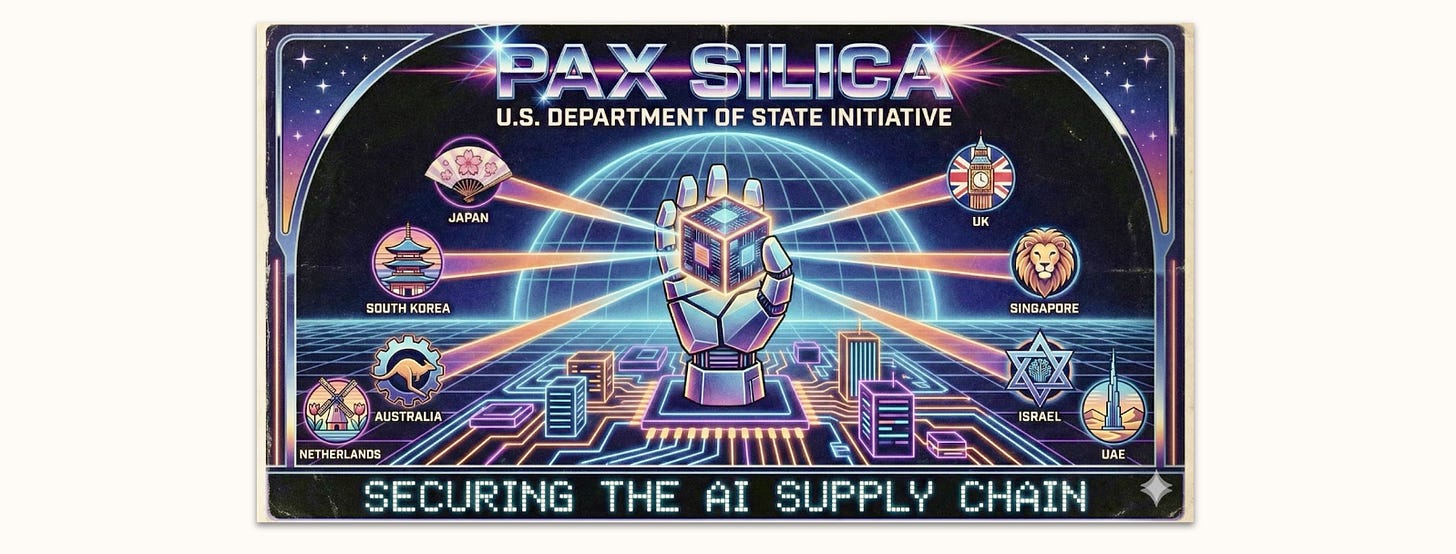

In that vein, last week, Under Secretary of State Jacob Helberg announced the ‘Pax Silica‘ initiative. It seeks to restructure bilateral alliances around access to critical technologies: an offer to import and partake in US software and AI infrastructure, in exchange for access to allied capabilities in semiconductor manufacturing, critical minerals, and advanced production.

All this comes just a week after the publication of the new National Security Strategy, which provides a stick to go with Pax Silica’s carrot. It formalised the ongoing American withdrawal from value-based, no-questions-asked commitments to its alliances — and led to reactions between apprehension and outright panic among Western allies. The headline story told is one of hemispheric consolidation to the detriment of the rest of the world.

But alongside broader American export and technology policy, Pax Silica offers a genuine glimpse of how one might rebuild and redefine the Western alliance – of how to make it durable in the face of international technological and domestic political disruption. It forces the alliance to grapple with an unassailable American lead in key technologies, and, though forcefully and a bit uncomfortably, invites allies to consider what their place might be in the face of it. That’s direly needed.

Yet for all the appeal of that prospective endgame, I fear for the midgame. Forging a new order is a difficult task – the Pax Romana was not announced via press conference, not instantiated by administrative decree. It wasn’t even really Roman policy. It flowed downstream of a hegemon’s reputation and international recognition, of which an embattled America has much less than ascendant Rome had. For a Pax Silica to hold, politics and policy alike still have to fall into place.

What’s to Like?

You, O Roman, govern the nations with your power- remember this!

These will be your arts – to impose the ways of peace,

To show mercy to the conquered and to subdue the proud.1

Trump or not, I feel the end of the old alliance paradigm was somewhat overdetermined. The Western alliance has long been stuck in an untenable division of labor, with the US increasingly dominating the most innovative and strategic sectors, further and further upsetting the balance of economic and military power and leaving weakening allies on the periphery of power. The resulting gap was already starting to take its toll both on European and American capabilities. Now, on the eve of a major technological revolution, the shortcomings of this setup are becoming clearer still; and no self-respecting middle power should have been happy to head into it on hopes of American good graces.

And so however comfortable the old transatlantic arrangement was at the ‘end of history’, I think it might have struggled to get this new era right. In contrast, Pax Silica offers the beginnings of a more robust paradigm.

Alliance Stability

The end state I imagine – what I take to be the optimistic read of Helberg’s ambition – is an arrangement between the US and its allies that fundamentally hinges on mutual technological leverage. Deals and arrangements are structured around allies providing something the US needs, in exchange for close participation in the American tech stack. This change away from deeper alliances built on normative commitment cuts two ways: it is more contingent and up for renegotiation, providing less unconditional assurance to allies; but it is more reliable in the face of quickly shifting politics, just as long as allies continue to be able to produce something America wants.

Many observers draw many kinds of lessons from the last few years, but mine is: in the face of volatile national politics everywhere, we need to stabilise alliances against topical disruptions from cultural disagreements and the politics of the day. Neither abstract strategic logic nor underpinning values have proven up to the task. Instead, building a Western alliance that can prevail means backing up our ties with hard leverage and mutual dependency – which is exactly the thrust of the Pax Silica. Nowhere is that more visible than in AI: middle powers need to find some way to reliably access advanced AI, but the danger of simply bandwagoning with the US is that expecting the US to provide its most advanced systems for free is not reliable. I’m not reassured by others’ hopes that things would be much different under a hypothetical Democratic administration, which might itself have security-based reservations about upsideless exports to allies. A reduction of alliances to mutual leverage, then, makes the bandwagoning strategy easier, not harder – because it insures the arrangement against unilateral reneging, just as long as middle powers keep up their part of the bargain.

A Path, of Sorts

You might say that a transition to this setting shouldn’t be the result of abrasive and unilateral US-led realignment – and in fact, I’ve repeatedly argued US allies should get ahead of the curve and shift their strategies toward a clear source of leverage no matter the US policy. But the fact is, a new order has failed to emerge naturally from the post-Cold-War set of alliances – the current division of labor is simply unworkable, the changes in departing from it too painful, and many major allies still stalwartly assume that things might be diplomatically difficult but not materially different.

Next to US intervention, AI in particular serves as a forcing function to dramatically change this arrangement – to improve it, in my view. That’s for two reasons: First, because AI puts the nail in the coffin of some allies’ approach to pursue a highly diversified economic structure, then execute on it worse than America does. Particularly in the software and service industry, where America has long outcompeted its allies but has left niches for local competitors, the story might soon be very different: advanced AI systems will sweep through these sectors, and likely lead to the accretion of more and more revenue with US software companies far away from the taxable economic activity in middle powers.

In that same context of middle powers’ economic structures, a Pax Silica setup also has the invaluable advantage of a favourable political economy. It does not ask US allies to become independent and competitive by reaching sovereignty through moonshots – which would be expensive, speculative, and dangerous, and has so far resulted in a broad portfolio of failing half-hearted attempts. Instead, it asks them to do what they’re already good at, and closer integrate it into the US alliance. That’s a much easier sell in domestic political economies, because it comes with at least the illusion of retaining economic structures and sources of national pride in the face of an otherwise disruptive trend. Selling Germany on ‘we’re building AI models now’ seems nigh-impossible; selling Germany on ‘we’re building industrial components powered by US AI in exchange for access to frontier capabilities’ seems like a better pitch.

Allied Scale for a Wary World

And second, because the sharpening AI race is also taxing US resources to an unprecedented extent. As America’s best and brightest, concentrated government support, and greater and greater parts of its capital market are poured into enduring supremacy in the AI race, other bottlenecks are becoming more and more pronounced. Upstream inputs into AI capability, like semiconductor manufacturing and high-quality data, are still very strong outside the US; and increasing AI deployment will lead to increasing downstream bottlenecks: robotics, advanced manufacturing, automatable R&D that actually allow for the translation of AI performance into real-world impact. The latter becomes particularly important as China is particularly good at expanding these downstream bottlenecks – in the logic of ‘allied scale’, analysts have remarked that coordinating allied manufacturing capability would be one way to counter the breadth of the Chinese industrial base.

One way to understand this, then, is that ‘Pax Silica’ might be the Republican word for ‘allied scale’. I think everyone in the West could find something to like about this.

What Needs to Change?

To plunder, to slaughter, to ravage, they call empire by false names; and where they make a wilderness, they call it peace.2

So much for the promise of the endgame; now to the perils of the midgame. For all the material benefits of this new order, I’m not yet sure that the world is buying what America is selling. My sense is there are two distinct challenges here – one of them comes from the pace of the transition, and the other from the actual terms of the deals.

Managing the Pace of Transition

The transition is the hardest part. No matter how attractive the substantive parts of a Pax Silica might be, they’re still a departure from what many US allies perceived as a better time – one where they could rely on the US not because they were providing something of value, but because they shared in common values. Moving from the latter to the former fundamentally asks more of middle powers, and breaks with a trust and certainty that the domestic decisionmakers had carried for decades. It also throws the domestic politics of these middle powers into disarray – again, take Western Europe, where local narratives hold that industry models have broken down in part because the US is no longer happy to foot the defense bill.

When the phase change in foreign policy comes with costs and inconveniences to allies and partners, they’ll have a hard time evaluating any new paradigm on its merits, and instead will be drawn to the comparative. Selling the Pax Silica to someone who was never a US treaty ally before could be the easiest thing in the world, and pitching it to long-standing US allies now would still feel like a downgrade and incur resistance accordingly. US foreign policy cannot be naive about this – the deals need to be better than they would be on objective merits to get buy-in at scale.

To make matters worse, the transition is also politically embattled way above the paygrade of AI policy. In the past, I’ve argued that the UK-US Tech Prosperity Deal is one model example for bilateral cooperation around critical capabilities for middle powers – but warned that any sectoral partnership was subject to an overarching volatility in US foreign policy. Just this week, it has been reported that US delivery on the terms of the deal has been halted – apparently because the administration is seeking UK concessions on unrelated matters of trade and foreign policy. This is exactly the kind of thing middle power strategists are worried about: if the US mixes international tech policy with its political desiderata, how can we trust the merits of strategic deals? Any visible examples of such a trend hurt the initiative at large.

I haven’t heard a good answer yet – ‘you’ll just have to deal with it’ is certainly not sufficient. Even if it’s true, it will inevitably make the middle powers stubborn and drive them into further sovereignty ambitions with no upside for the US. If the Pax Silica is a strategic priority, it needs to impose a degree of message and negotiation discipline across the whole of American foreign policy efforts, or it will fail.

Structuring the Content of Deals

And then there are two problems on the horizon relating to the actual structure of Pax-Silica-style deals with middle powers.

The first is that today’s deals still take place in a precious microcosm. None of the Pax Silica members – and arguably not even the US at large – understands AI and its input technologies as a strategically critical area just yet, and in pure macroeconomic terms, it still plays a minor role. In an emergent sector of no systemic relevance, it’s fairly easy to convince technocratic operatives of leverage-based bilateral treaties. The stakes aren’t all that high, and the domestic political attention is basically non-existent – the undersecretary level is frequently free to move on tactical merit alone. That will drastically change once AI reaches political and economic salience; once constituents and companies start asking questions about sovereignty, regulatory leverage, safety of access and security of deployment. Ideas about autarky, skepticism of America, and a barrage of political concerns will muddy the waters.

Put differently: it’s already hard to make a Pax Silica deal about 1% of your GDP; now imagine making a deal about 20%. In a political environment where approval of both AI technology and the US is low and keeps decreasing, it will be very difficult to domestically justify deals once the technologies involved become more and more relevant. Leadership in middle powers and US foreign policy should both take note, and give allies’ electorates as little reason as possible to politically reject a favourable deal in the future.

The second problem is that the US is seeking to reshore the same capabilities they seek out in allies, thereby giving the impression that the deals themselves are not stable. The pitch for a deal is that an ally can rely on it because the US so desperately needs the imported capacity – and yet, America is aiming to recreate the same capacities at home. That reads as a major threat to these allies, and could derail favourable deals on two levels.

First, it might make allies think that a deal is fundamentally time-limited – that they are on borrowed time until the US recreates the capability at home, and that they’ll lose access to whatever they’re getting in return once that happens. That makes it much harder for these allies to do what the US wants of them, which is pivot their economies toward strengthening that capacity at home: if you have to assume that demand is set to collapse once the US has finished reshoring, you can’t take ambitious bets on ramping up supply.

And second, it might make allies think that cooperating closely with the US is particularly risky because America seeks to extract their advantage. A deepening cooperation that includes tech transfers might make it easier for US firms to replace allied champions in the future: if a cooperation with ASML went deep enough to allow for the manufacturing and maybe even development of EUV at scale in America, the Netherlands wouldn’t be building a durable niche as much as signing away their advantage. Now this is easier to do in some cases than others – unless you’re foolish enough to sign away mining rights to raw materials for cheap, raw materials can’t really be reshored to the US –, but it’s a latent risk that will be salient to the involved powers.

In a somewhat tragic symmetry, both these reasons mirror past relations between US allies and China – allies started exporting machinery to China, just for Chinese companies to recreate the exported products, collapsing demand and developing competing products. The resulting shock has already disrupted especially European economies at their core. They’ll need a good reason to think it won’t happen again.

Outlook

What does this all mean in practice? There is optimisation potential in so many areas of this ambitious attempt at a new order – as befits the scale of the challenge. The technical implementation of the Pax Silica’s champions in the State Department needs to be careful not to disregard the strategic sensibilities of promising partners. The broader Trump administration will have to shape some of its international politics around this plan, even at some cost to cultural or trade priorities.

And someone will have to make the actual case to middle powers that all this is worth going for — by translating the sometimes jarring sound of US alignment into their strategic parlance and helping them chart a course accordingly. That last part is perhaps the most underrated, and most worth working on.

The Pax Romana did not emerge from declaration, but from decades of calibrated coercion and credible commitment. The Pax Silica, if it is to mean anything, will require the same – a tall task for the Trump administration. In many ways, coming up with a new structure for the free world has been the easy part. The hard part is convincing allies that America’s word is worth building a paradigm around, at the exact moment when many are losing faith in it. The practicality of this order needs to be proven soon, before the politics of AI derail progress on this narrow path.

Perhaps the first articulation of the Pax Romana, from Vergil’s enormously influential Roman founding myth, the Aeneid.

Tacitus’ Caledonian war chief Calgacus, offering a somewhat less optimistic outside perspective on the Pax Romana.