The Future of AI Export Deals

AI developers can build moats by making country-level exports work for everyone

These days, when you glance at the top technology news, the odds are decent that you’ll find announcements of increasingly contrived partnerships between AI developers and atrophied legacy institutions. In the ensuing whirlwind of news updates, diagrams of investment flows, and hasty takes on what this means for “the bubble,” I think we’ve missed the most interesting category of deals: between major AI developers and governments. Just on the OpenAI side, the last month has seen announcements of Stargate Argentina, a country-level deal with Germany, and a narrower Stargate UK hidden away in a broader UK–US tech deal. Today I want to offer some thoughts on why these deals are underrated, and how to make them work.

I believe country-level deals matter for two reasons: First, they could become an increasingly important part of company strategy: compared to fleeting arrangements with other software companies, country-level deals potentially offer longer-term arrangements, exclusive capture of some important tier-2 markets, and inroads with governments that will matter as strategic relevance of AI technology increases. By creating lasting, sticky deals with national governments, AI developers can potentially build huge and lasting moats at a time where commodification is a looming threat.

Second, country-level deals are a major variable in getting international diffusion right. In many countries, private and public sector alike often underappreciate the economic and strategic relevance of AI, leading to underinvestments and misallocations that could strip their governments, citizens and businesses of critical capabilities. Few actors have both the incentive and the leverage to fix this – but AI developers pursuing country-level deals do.

The best version of these programmes is exceedingly good: they stabilise the market against the volatilities of Silicon Valley, and they provide for the equitable distribution of groundbreaking AI capabilities. Their worst version is exceptionally bad: they sell useless computing infrastructure to countries who can’t run it, and discredit AI developers and their technologies the world over. Of course, much of the difference will be up to public policy, and I’ve written about both the importers’ and exporters’ side before.

But many of the most important questions instead come down to questions of firm-level program design. So, this piece rethinks the debate and policy implications around developer-side strategy, starting with a sober assessment of how far apart the AI industry and many importers are today.

Where Things Stand

Right now, these programs are still in their strategic infancy. They also overlap with preexisting hyperscaler initiatives, where developers have long built datacenters in other countries to reduce latency or navigate data governance. As an attempt to delineate, this post will try to deal with country-level deals, i.e. agreements aiming at the provision of AI capabilities struck principally between American AI developers on one side and involving foreign governments on the other.

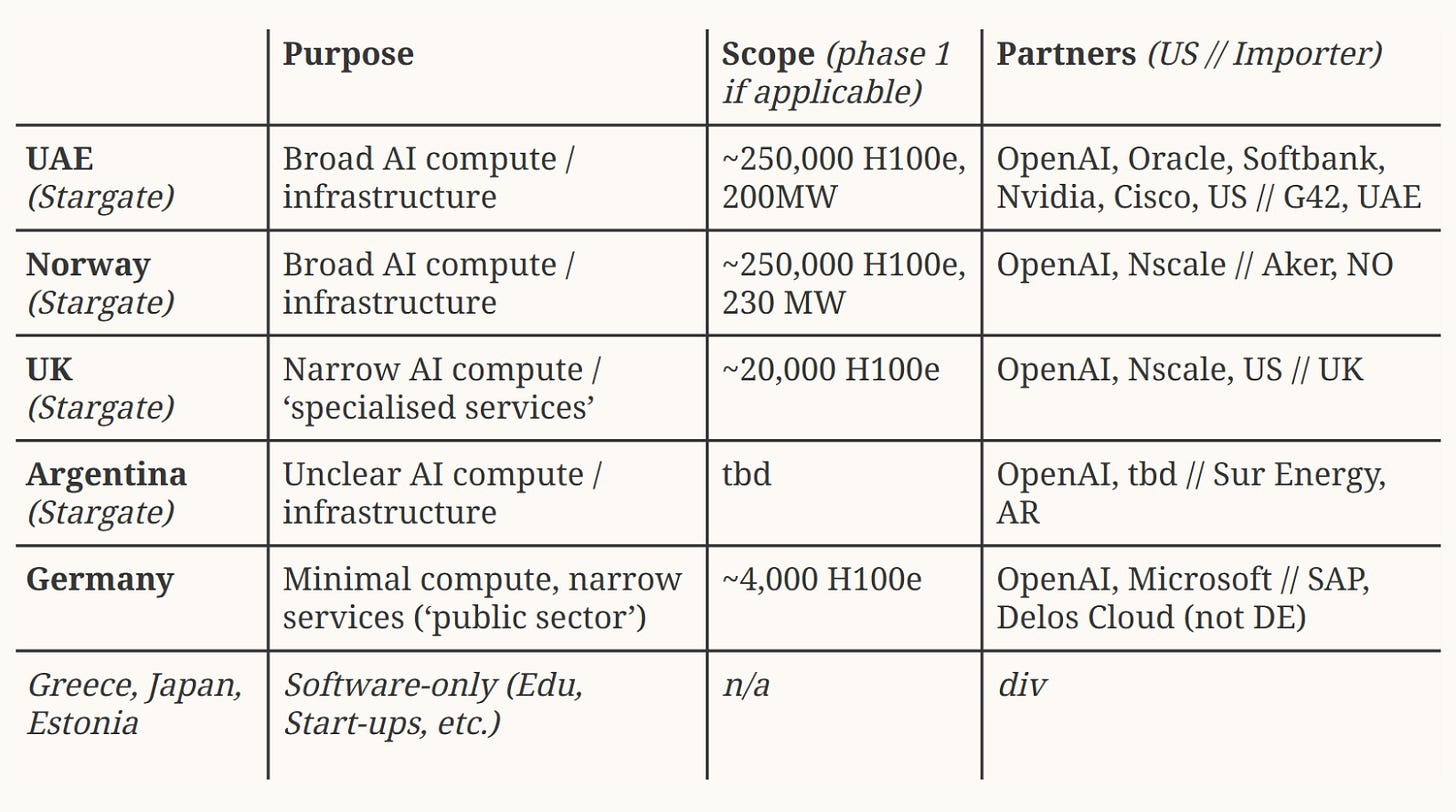

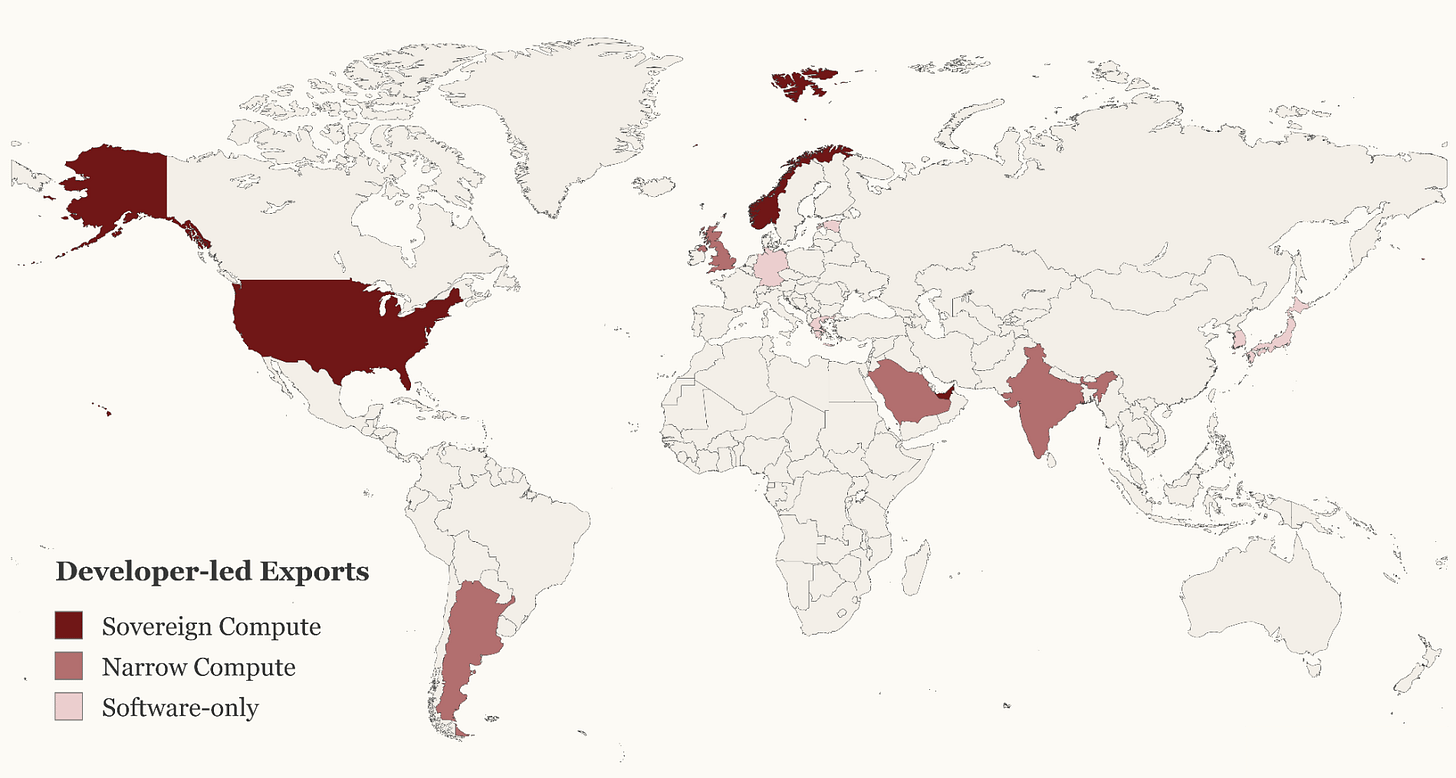

For many reasons – some of which will soon receive some further examination on this blog –, OpenAI in particular has been excited to engage in just about any deal. The resulting portfolio of announced ‘OpenAI for countries’ deals is a good overview of the strategic pathways these programmes can in theory go down. Some other developers have also pursued some export ambitions, but they’re harder to categorise: Google’s expansions, for instance, are deeply entwined with their standard hyperscaler business. So for the paradigmatic case, let’s start with a look at OpenAI’s announced export deals:

We can glean three general directions for country-level deals from this:

Sovereign compute deals aiming to export enough infrastructure to run inference and training at scale, for a broad range of application and purposes. This is the Stargate UAE model: enough chips to do basically anything, with a well-understood interest on the side of UAE firm G42 to provide inference for the region and train its own models down the road.

Narrow compute deals aiming to export enough infrastructure to run inference for specific applications and use cases. This is perhaps the Stargate UK model, which provides for only 20.000 H100 equivalents and earmarks them for specific purposes in the public sector.

Software-focused deals that mostly create specific conditions to deploy or fine-tune existing software products in coordination with local stakeholders.

This piece is mostly about the former two – deals that include some version of compute. Selling software is nice, and it’s good inroads for future deals, but I struggle to see how in itself, it’s a particularly sticky export. The technology is still a little bit too early to determine where exactly switching costs usually accrue, but it’s my sense that the infrastructure layer is by far the most robust bet: it’s the most capital intensive, the most deeply entrenched, and the hardest to resell and repurpose for other issues. If you buy a datacenter, you’re largely stuck with it. So I’ll focus the rest of this piece on export schemes that include some infrastructure component, and think about where their strategic refinement might go.

So what do you have to get right to build a version 2.0? I think it’s most useful to think about how to design export programs in terms of tensions between conflicting desiderata. I think the following three trade-offs map the terrain well.

Three Trade-Offs

Switching Costs vs Sovereignty

From the perspective of a developer, you’d want to deeply entrench your exports in a way that makes switching away from them down the road more difficult. There are some ways to achieve this, but the most obvious one is through infrastructure. Infrastructure deal components create switching costs on two levels: first, maybe the contractual stipulations on the use of the exported infrastructure explicitly require the use of your models and no others. Second, maybe you export infrastructure that is specifically very good at using your models, and so switching would cause inefficiencies and incompatibilities without any objectionable contractual features.

The second element is an underrated reason for AI developers to get their hands on ‘in-house silicon’, i.e. proprietary chips specifically developed to run their own models. Google is the obvious leader in that space; current generations of their TPU chips seem to provide actually competitive performance. This is also a lens through which to view the OpenAI-Broadcom deal: next to general diversification away from Nvidia, it specifically enables OpenAI to export strongly path dependent infrastructure bundles.

But all these techniques to drive up switching cost trade off against importers’ wish for sovereignty. Many countries in the world have an appetite for a reliable supply of AI capabilities that does not leave them susceptible to foreign leverage or restrictions. Right now, OpenAI can get away with calling their Stargate-tier offerings ‘sovereign’ compute because they’re relatively a lot more sovereign than a ChatGPT Business subscription and a handshake with Sam Altman. But they’re often not seriously sovereign in the sense that a country might want a sovereign supply of, say, energy or food: they require maintenance and continued provision of models at minimum, and the higher you drive the switching costs, the less sovereign your exported solutions will be: if you import infrastructure that leaves you de facto dependent on a single developer’s exports, you incur a substantial dependency. Developers will have to thread the needle between designing exports sticky enough to be profitable, and sovereign enough to be viable for buyers.

Next to the question of importer demand, the sovereignty trade-off also raises the question of how closely to align your program with the US government.

US Alignment vs US Alignment

The US government wants to be associated with AI exports. It fits both the broad goal of ‘dealmaking’ and the narrow goal of ‘AI export promotion’ aimed at maximising American tokens served. That gives developers threefold incentive to steer close to the USG in their export efforts: they receive explicit financial and diplomatic support in the context of export promotion; they benefit from importers’ interest to remain in the US’ good graces through making a deal; and they can be assured the USG won’t make life harder for them around compute export limitations. Because the export promotion framework is not finalised just yet, we don’t quite know broad the administration’s interest in calling deals ‘export promoted’ is – but there are some early signs that most AI-forward infrastructure deals will be invited to fall under the umbrella.

On the other hand, close alignment with the USG is risky in dealing with many major importers, especially with regard to the sovereignty question outlined above. Following the last months in trade policy, some countries have grown wary of American leverage, and have in fact stated it’s their policy to diversify away from US influence over their supply chain. AI developers on their own might be able to claim they’re ‘exporting sovereignty’ – I think this has worked somewhat decently to justify marginal datacenter deals in the UK and Norway, for instance. But the more overtly involved the USG is, the less viable this is. The OSTP Director and the AI Czar have repeatedly publicly stated that making the world run on American exports is their strategic priority; if they then laud and push a given deal, it’ll be hard to convince importers that it actually helps their sovereignty. So on some occasions, it might be in developers’ and the administration’s interest to reduce the affiliation of a deal with the USG.

How will developers balance that trade-off? Next to the target market, it also depends on their general relation to the administration: if that’s rocky to begin with, you might think you don’t have much to lose from disassociating just a bit – or even that the public record of your fraught relationship makes you more trustworthy in the eyes of skeptical importers. But if your relationship to the administration is strong and you work to maintain that, it’s hard to believe any import deal would be worth risking it. The administration can also do its part – by strategically allowing some developers to position far away from it to ensure that American exports happen even to US-skeptical importers.

Present vs Future Demand

How do you sell AI to a largely uninformed world? You almost necessarily face a difficult trade-off. First, you want to sell capabilities that these countries want and need right now: there’s an actual seller’s market in some parts of the world, and you want to get in on that. But often, current demand is mistaken: many countries don’t actually get AI, and have no real plans on what to do with the datacenters you’ll build for them. Over time, their demand might shift substantially – and in five years, they’ll want something else entirely and perceive you as not having delivered on capabilities they actually need. There’s also a future market obscured by importers’ ignorance: many countries that today still cling to unrealistic ideas of local champions or toothless adoption strategies will soon be in the market for large-scale AI imports. Servicing that future demand is much harder, because it involves identifying and eliciting it through arduous bilateral work; but it’s much more attractive, because it promises much more lasting demand.

One specific version of this point is this: There are two competing trends in effectively selling technology to countries: providing a ‘turnkey solution’, a standardised product that provides for a set of capabilities; and regional customisation, where you create bespoke solutions and integrations through regionally deploying manpower and development resources. Both of these ideas borrow from highly successful past Chinese products – the former from infrastructure, where China has been able to gain ground on exports by offering immediate ready-to-go solutions for computing, transportation or energy, and the latter from software, where China has not just exported basic software products, but deployed engineers to deeply integrate them into existing regional software ecosystems, such as in Southeast Asia. This has deeply entrenched the Chinese software stack in a large part of the region. In principle, both approaches have their merit – but there’s a natural risk to make exciting deals and gravitate toward the easy solution today, missing out on much deeper market capture.

Trying to thread the needle between the two and selling robust infrastructure with real option value is perhaps the most durable pathway. It’s also what developers today will claim they’re doing when pushed on this trade-off. But it won’t always work. Different use cases frequently require different scale and type of infrastructure – for instance, a country that first wants large clustered training capacity and ends up needing low-latency decentralised inference capacity for manufacturing can’t be serviced through one robust project across time. There are many such divergences: between training and inference, between clustering and decentralisation, between frontier capabilities and narrow industrial integrations, between broad general-purpose exports and targeted public sector capabilities, and so on. At some point, you’ll have to choose – and it’s very risky to leave that choice to misinformed importers alone, lest you fail to keep up with their future demand. The most successful export initiatives might first help importers to develop the best sense of future demand, and work with them to meet it.

Three Outlooks

These trade-offs carry threefold implications: for developers, for the American government, and for importers.

On the developer side, the trade-offs might best be thought of as a pick-and-choose list of features to configure your export program around. There are a couple of obvious permutations of choices that line up nicely with preexisting strengths and weaknesses of some developers:

In the trade-offs between sovereignty and switching costs, some developers are simply better-suited to capture some markets than others. Developers with good and abundant in-house silicon – perhaps Google – are well set-up to create deep infrastructure-layer lock-in that will feel convenient, but not sovereign. Developers that lack this kind of compute – think Anthropic and perhaps some newcomers – can make a virtue of necessity and position themselves as partners of choice to countries with a particularly strong appetite for (the illusion of) sovereignty.

Developers ready to go today can capitalise on their head start by saturating markets with substantial and somewhat informed current demand, taking quick wins to spin them into path dependencies, while developers that will still need some time to ramp up can take the time to conduct deeper bilateral negotiations, figure out personalised solutions and create deeper inroads with more respect to future demand. Or you might think that some developers might steer close to the US government and enter markets where strategic backing is valuable or necessary, while others can keep their distance and expand into more US-skeptical markets instead.

If you care to extrapolate some of these lines of thinking, I think you’ll agree that the incentives line up nicely with some of the leading developers’ profiles. If they follow down the branches of their comparative advantage, I think we’re due for a productive division of the world of exports. But in the face of short-term market incentives it’ll be hard to resist competing for the lowest denominator of cashing in on today’s most boosterish ‘sovereignty’ ambitions instead. If runway allows at all, developers would do well to consider the advantages of creating a durable market instead.

Second, there are lessons in these observations for the USG and its export promotion program: looking at where the market incentives point helps identify which parts of exports don’t organically happen under the current policy paradigm, and thus might need some more specific support. Two interventions seem promising:

Let some exporters stray away from obvious US affiliation. When faced with a choice between a country importing American AI outside the export promotion umbrella; or the same country importing Chinese AI or launching its own sovereignty ambitions, the USG should still favour the former: it still depresses the Chinese stack, it still retains indirect leverage via US regulation of exporters, etc. And so allowing some developers plausible deniability to launch their own export programs that allow for a lot more sovereignty and a lot less USG affiliation ultimately serves the American strategic interest to capture even markets that would otherwise bias towards importing from adversaries.

Focus promotion efforts on strategically valuable, but economically less attractive packages. Building bilateral relationships with medium-sized markets is really hard and takes a lot more time than selling to someone who has already opened their sovereign wealth fund checkbook. Deploying engineers to integrate the application level into local ecosystems is much more burdensome than building a datacenter and calling it a day. It would be easy for the USG to subsidise the easiest versions of exporting, see them happen, and call it a win. But making inroads in countries that require more massaging should be a priority – a good export program makes things happen that otherwise would not. That means focusing financing and diplomatic support on difficult deals that otherwise would not happen, especially those that require demand elicitation and customisation at scale.

Third, thoughtful importers should make themselves more attractive targets for export deals. That doesn’t require aggressive spending or submissive negotiation as much as it requires strategic clarity. Because developers should be very interested in creating deals around lasting demand, but are stretched too thin to elicit that demand everywhere, simply having a clear strategic view of what capabilities you need is already an advantage for an importer: it signals to the exporters that going for a deal with you has strategic value. A similar logic applies to convening consortia; if your government can get together a group of strategically clear-eyed buyers with operationalised capability asks, the exporters have something to work with.

Ultimately, if you’re a middle-of-the-road importer without a huge sovereign wealth fund or gigawatts of energy infrastructure to deploy, you’re not the first port of call for an ambitious exporter by default. A cheap way to keep up is to realise what an exporters’ ideal deal landscape looks like, and then work to create it. Most of that is being able to tell a convincing story about why an export deal confers a lasting market advantage to a developer, and a decent strategic upside to the USG.

To get the best version of AI exports, we’ll need all three parties of an export deal to play their part. Ignoring the market incentives is a surefire way to fail at that: the obvious risk is that AI exports collapse to only plucking low-hanging fruit, failing to proliferate capabilities well and allowing an in for a Chinese export product down the road. Making international diffusion work requires seeing where the developers’ incentives pull — design policy around that.