Making American AI Export Promotion Work

How to sell the American stack to an uninformed world

The Trump administration has set out to make the world run on American artificial intelligence — and has started drawing up the policy details to deliver on that vision. The conversation around this export promotion is perhaps the most underrated issue in international AI policy today. It offers the ultimate win-win perspective: entrenching and securing a durable US-led global AI ecosystem, while cutting the rest of the world in on the promise of advanced AI. More so than any other international piece of AI policy, something good might actually happen here:

For countries at risk of being left in the dust, export promotion can deliver frontier capabilities while providing a direly needed forcing function to find a strategic and economic niche.

For the US, getting export promotions right today means undercutting China’s global influence and AI stack effectiveness before it becomes mature – capturing the world while China is still ramping up production.

For a world fearful of volatile conflict between the US and China, a successful export promotion approach could strike mutually beneficial deals to entrench the US stack worldwide – deciding the AI race by flywheel effects and spheres of influence instead of military conflict.

Policy action is already underway. Full-stack exports feature prominently in the Action Plan and in statements by senior White House staffers alike. Pursuant to a recent Executive Order, details on the export promotion scheme are being developed, and a program is to be established by October 21st — so now is the time to get it right.

But in scoping out this program, difficult challenges must be met. The relation between government-promoted exports and extant private projects remains unclear. Most critically, export promotion is caught between an underdefined supply and an uninformed demand. The resulting gap can derail export promotion: Exports sought by importers who are mistaken about their own needs do not create path dependencies, exports aimed at what importers will need three years from now might not be in demand today. Getting it right will require avoiding diplomatic backfire risks, as well as building strong promotion vehicles around the right export stack.

The Promise of Promotion

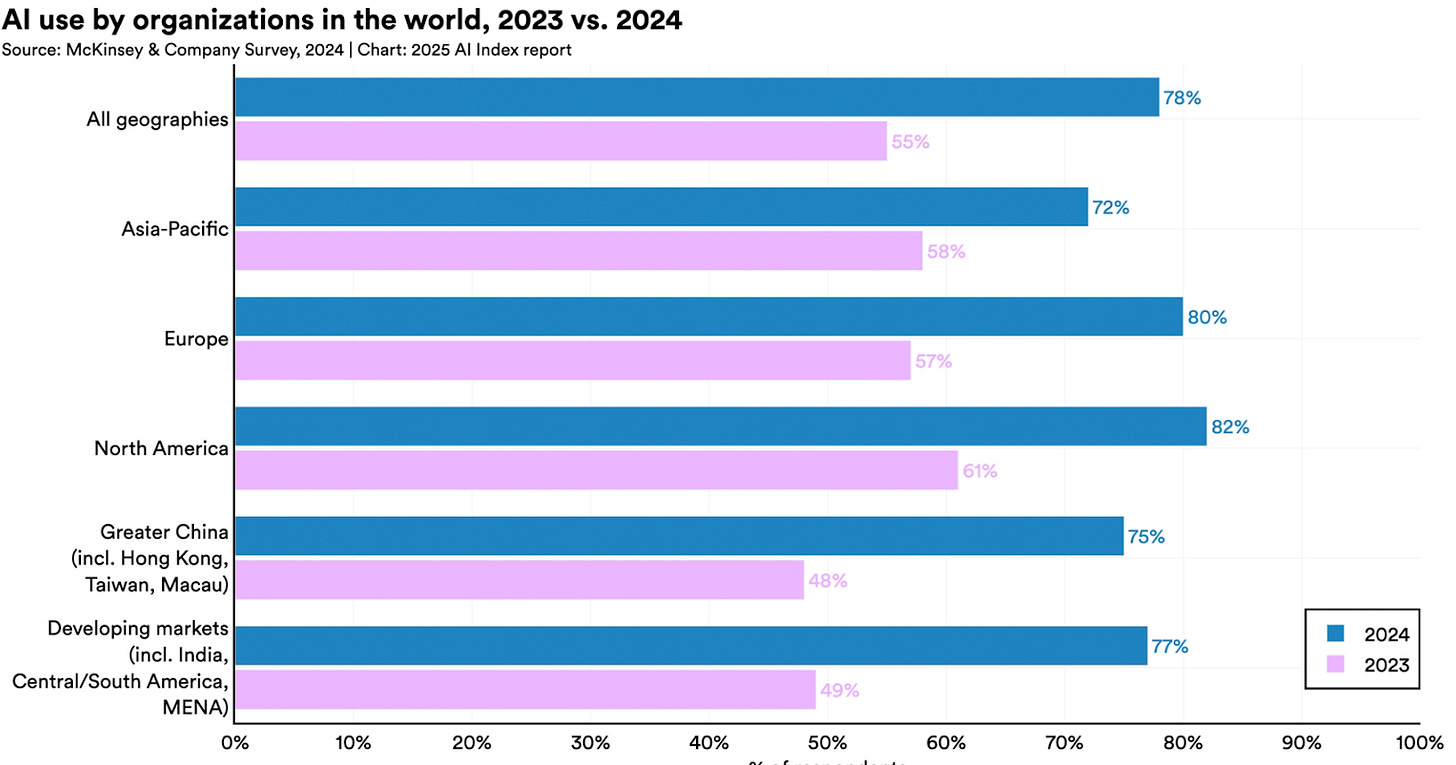

What makes me so optimistic about export promotion as a tool? I think that current efforts at diffusing AI to most countries are often led by importing countries that don’t get what’s going on. That leads most current import strategies to be in service of absurd goals formulated in dire lack of situational awareness: the likes of training frontier models on 100,000 H100 chips or reaching inference sovereignty in a country with record-high electricity prices — with no clear payoffs to the US. Many importer-led schemes, as delivered by the current market, don’t serve importers’ or exporters’ interest.

The export promotion story looks different. Ideally, the US should be actively looking to strike deals to facilitate the export of consortium-based ‘full stacks’ of AI technology: US firms build and run a datacenter that services US-built AI systems in a foreign country. The US government has a range of tools available to foster these deals:

Financial, such as loans, guarantees, and insurances;

Coordinative, by getting together and aligning a consortium; and

Diplomatic, by conducting negotiations on behalf of the export plans or tying these plans into broader foreign policy initiatives.

The US is motivated to do so on three grounds: create a lasting global revenue base for their AI industry; undercut future Chinese export ambitions; and set up a ‘flywheel effect’, in which broad deployment of US systems feeds quality improvement to American hardware and software.

That makes it likelier for these deals to happen – but they are also likelier to be good deals. That is because the US government and private sector have a vested interest in delivering a useful solution. The goal of export promotion is not just to make a quick buck on selling a couple of chips, but to create enduring demand and tech ecosystem integration. If the US were to sell a useless stack, countries might still turn around, develop proprietary solutions or go for Chinese imports later instead.

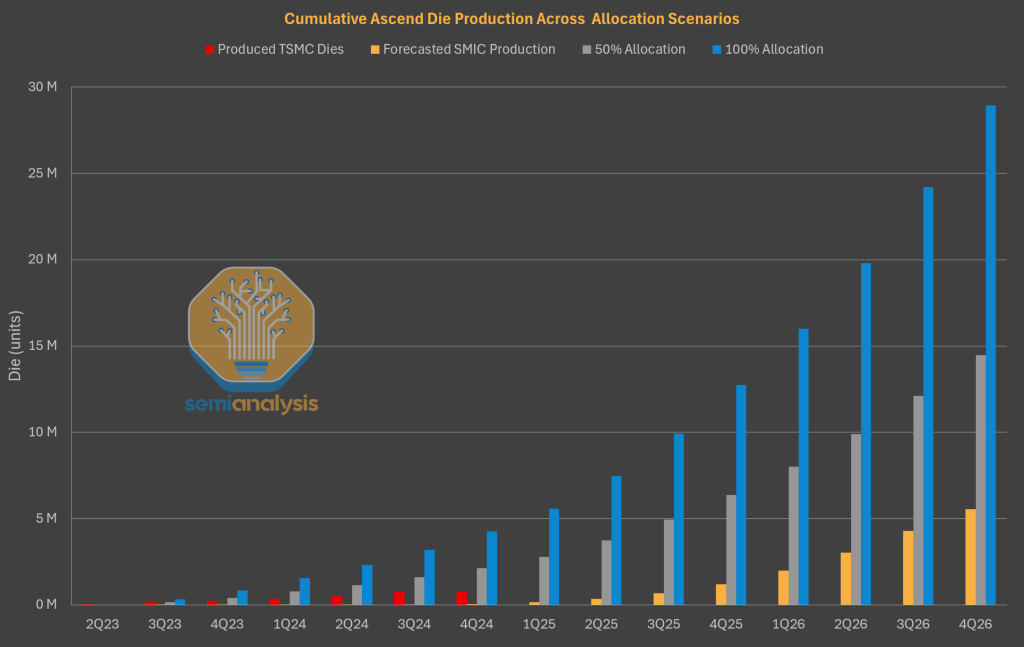

So to win on exports, America needs to export lasting path dependency on the US stack. It’s an urgent matter: there are just a couple of years left to entrench the American stack. A Chinese export platform, highly subsidised by its government, is a threat to US market share – but it’s still a few years out, mostly due to Chinese chip manufacturing constraints. It’s important to get exports right before Chinese exports happen. Export promotion is an attempt to capture that moment, and so aligns incentives that are otherwise far apart: The US wants to seize the window of opportunity to provide countries with capabilities they need, so they don’t get them somewhere else.

What’s Not To Like?

Skeptics of export promotion will tell you two things. First, that we can just get this future without explicit promotion – foreign government will just naturally import. I think that’s mistaken. An export promotion framework means there is way more US buy-in, making deals happen that otherwise wouldn’t – because the US supports the deals, encourages importers, and is incentivized to get them to understand AI and where it is going. That’s aligned with American interest, because the US should get in on favourable deals before the market gets around to them, creating early path dependencies and widespread adoption of its stacks. In a rare current moment, the US is facing a closing window to win – and is thus incentivised to move fast on diffusion.

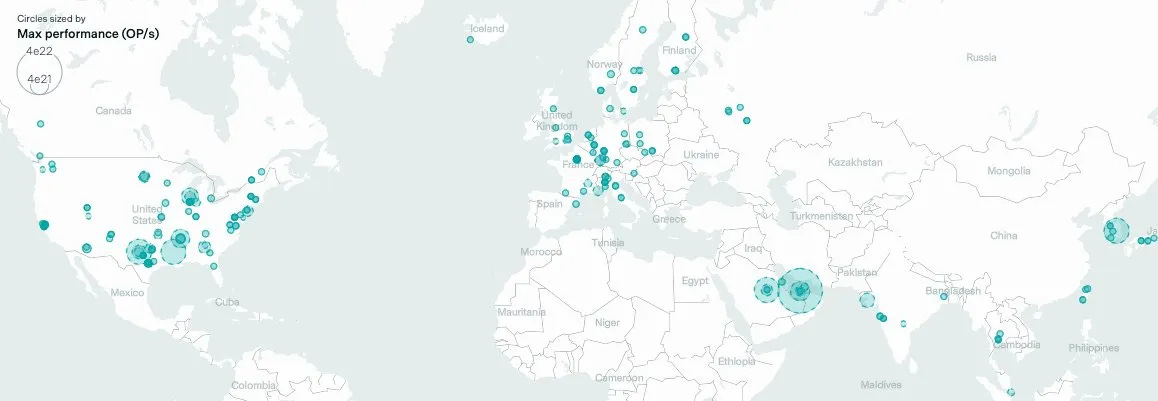

Second, critics will tell you that export promotion is at best a niche cause: most AI exporting might not happen through nation-led deals, but through private businesses selling to private businesses – like in the cases of American hyperscalers creating datacenter capacity in Europe in the past. I think this is true by volume: I expect most of the local computing capacity to be created where hyperscalers believe they should build out their inference and training capacity. And I think governments should generally not be in the business of elevating run-of-the-mill hyperscaler projects to a matter of national ambition.

But it’s not true by quality. Export promotion done well can facilitate the proliferation of some of the most important capabilities. Hyperscaler expansion alone does not make for an enduring shift of AI access. Especially in countries with a small footprint in terms of economic demand for AI systems beyond consumer apps and API access, non-promoted market forces alone seem unlikely to service durable import deals. And many important functions will not be provided by importers’ domestic private sectors alone, especially as they relate to public use of AI systems: as a government or national security resource or as an instrument for public research or education. Local servicing of specialist public-sector-focused use cases, not unlike Stargate UK, could be one blueprint for a good export – just that you’d need to promote it to get it done anywhere but in the very AI-aware UK. Private incentives get you unstable access for incidentally profitable areas. Durable diffusion is not a default, and might be the outcome of export promotion instead.

Still, detractors have a point: Promoted exports will have to go where the market currently does not – otherwise you wouldn’t have to promote them in the first place. But promotion does not imply a deal would otherwise be bad – my sense is that much promotion will aim to hasten a deal that would ideally happen much earlier, but are paralysed by lack of awareness or capacity. They are mostly trying to make good deals happen sooner. But there’s a lesson in the objections for the US government regardless: if these deals are supposed to go beyond signing off on natural market moves, there need to be substantial and actually helpful promotion efforts.

Export promotion as a framework of international AI diffusion is very much worth being excited about. But a minimal implementation of the Executive Order is not set up to deliver on this optimistic perspective. The awareness gap persists: Buyers don’t want what they should want, the sellers don’t know what to sell. Let’s start by looking at the buyers.

Buyer Ignorance

By and large, governments of likely importing countries don’t have a strong understanding of what they should buy – or that they should buy at all. This is the core issue that has made a successful exporting approach without promotion so difficult, but it remains a problem even if the US government plays a more active role.

Very broadly, I suspect there are two ways in which buyers are getting this wrong.

Importing countries that know AI is somewhat important often want to achieve ‘sovereignty’. That makes them interested in imports, but only on their terms: They might want to import GPUs, but want to be able to control them, no US datacenter providers cut in. This is the story behind initiatives like the EU gigafactories. Policymakers in these countries have looked upon the UAE deal and grown concerned – they see the involvement of US consortia as restrictive to the way they can use the GPUs they buy, surmising they’re not getting ‘real’ sovereignty by the deal.

They’re somewhat right about this, but are missing the fact that even sovereign control of incidental heaps of chips doesn’t do much. Between replacement cycles and continued dependence on models, you can’t actually buy sovereignty. Still, this sovereignty ambition might make countries less likely to engage with the US’ preferred export models and build unhelpful projects instead. This is not just a problem for importers, but for the US as well, because you don’t get these sovereignty-minded countries onto the full stack early enough – which has them participate less in the overall US ecosystem, and makes them more susceptible to Chinese exports once their original ambitions fail. This is a notion that still dominates the domestic conversation in some of the most potentially-profitable and strategically important importing countries – South Korea, Germany, and France, to name a few.

Many countries also don’t have a strong notion of their demand just yet. Some political environments are keen to dismiss AI as hype, others have illusions about the viability of some locally developed stack or paradigm, others still assume they can muddle through on general API access without national solutions. Substantively, they often haven’t figured out strategic and economic needs: will their economies require large amounts of low-latency inference? A lot of fine-tuning capacity? Ability to process privileged data locally? Large-scale proprietary training infrastructure for narrow AI?

Depending on the answers to these questions, they’ll require different imports. You might give them expensive, low-latency compute and create a market for cheap, slow mass inference instead; you might give them low-security commercial capacity where they’d need high-security capacity for government use or vice versa; and so on. Give them the wrong stack, and future demand not met by US supply might be an opportunity for China’s exports. Even worse: High-profile failures of the US stack to meet importers’ demand give China salient benchmarks for its own export ambitions.

To make matters more difficult, strategic confusion is frequently paired with an apprehension toward making deals with the US in particular. The adverse consequences of this position might not become visible all that quickly – and might even be reinvigorated by transitory market corrections. I know that many governments register high-level interest in importing right now, so you might doubt that concern. But as import deals get closer to completion, I believe these political hurdles and demand mismatches will become more and more important – and I wouldn’t be surprised if many initially enthusiastic negotiations broke down over time.

As a result of these misapprehensions, buyers of both kinds might organically realise their demand for importing a US stack too late. This is a problem not just for them. The viability of an export-forward US strategy increases the earlier the exports happen. Both the self-reinforcing flywheel effect that hinges on widespread adoption and the idea of preempting Chinese exports, which are not happening just yet, should have you place a premium on getting in early. Mismatched demand is a major challenge for export promotion.

Sellers Beware

These buyer preferences inform the design of the export stack at a time when many design elements are up in the air anyway. The US government and the private firms providing the AI stack haven’t quite figured out two things: what exactly to sell, and how to promote it.

Promotion Avenues

Starting with the latter, the US government must make sure to aim promotion at the right kind of deals. For an export promotion scheme to add surplus value, it needs to enable deals that otherwise wouldn’t happen. But that must not mean subsidising deals that otherwise lack economic viability. Instead, export promotion should be about overcoming inertia and lack of institutional awareness: Make good deals happen earlier by getting importers to understand they’re mutually beneficial. But even overcoming inertia this requires a substantive push. It’s not yet clear how the US might deliver it.

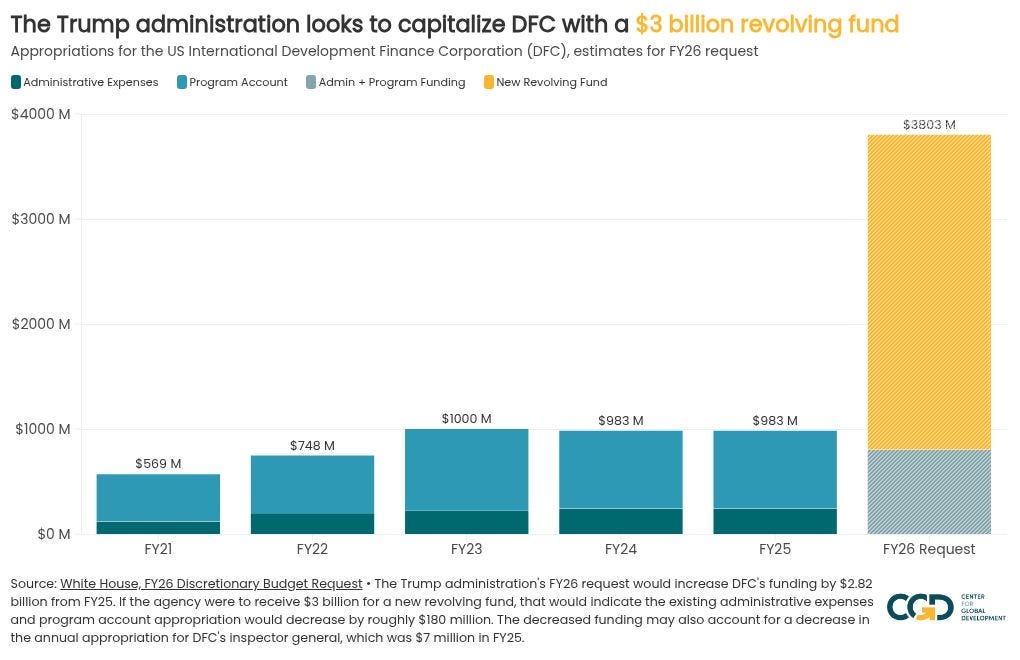

The first and most obvious angle is through coordination and negotiation. But in many critical areas of implementation, the US government is reportedly already understaffed. Agencies responsible for negotiating satisfactory bilateral deals are unlikely to have the manpower to assemble bespoke consortia and convince buyers who are somewhat unaware of their attractiveness. Financial support is an obvious alternative. But it’s as of yet unclear how much financial support the US government will be able to provide. Making exported full stacks affordable enough for the deals to become an obvious buy, as China has often done with its exports of critical infrastructure, is very expensive. Key US vehicles like EXIM and DFC are already spread thin, and additional appropriations are very difficult to secure. If there is enough political support to aim extant export promotion resources at AI exports, the financial contribution might be substantial enough – if.

Of course, neither scaling up staffing nor subsidies is beyond theoretical reach – but both face a difficult political economy in an administration that has made early and loud commitments to cutting back on overstaffed departments and international spending.

If the US does not manage to consolidate political support for putting in the work and money on bilateral negotiations and export subsidies, I’m concerned the government might resort to broader diplomatic pressure as its main lever for export promotion. It could tie its asks for import deals to other questions of foreign policy, such as broader trade and tariff policy or military cooperation, such as on Ukraine. That sounds cheap and attractive in the short term, but could easily backfire: As laid out above, the sovereignty ambition is already a major hurdle for export promotion. If the promotion program gives importers the impression of detrimental dependencies and losing leverage from the get-go, bridging the supply-demand gap becomes much harder. The US government and exporters alike can prevent that: building enough negotiation capacity and subsidy options on the US side; and easing negotiations by developing a clear picture of domestic demand on the importer side.

Shape of the Stack

On what exactly the government should sell, the underlying executive order points out that this stack should include:

(A) AI-optimized computer hardware (e.g., chips, servers, and accelerators), data center storage, cloud services, and networking, as well as a description of whether and to what extent such items are manufactured in the United States;

(B) data pipelines and labeling systems;

(C) AI models and systems;

(D) measures to ensure the security and cybersecurity of AI models and systems; and

(E) AI applications for specific use cases (e.g., software engineering, education, healthcare, agriculture, or transportation)

The reasons for the full-stack focus are clear from the government’s overall approach: Market share and flywheel effects alike are most pronounced when the stack includes all layers. And there’s some attractiveness in exporting turnkey solutions: it reduces expertise required on the buyers’ side. Instead of having to formulate demand for GPUs, bandwidth, and data, importers can simply name a capability they’d like to import, and the US can deliver a full-stack solution enabling that capability. The upshot is a simpler shopping experience, easier to explain and justify – anyone who has ever worked in national procurement will agree that is an underrated merit.

Still, that’s quite the stack to be exporting all at once, and leaves some unclarities. It’s unclear, for example, why you need to export data pipelines and labeling systems if you already deploy finished AI applications to the datacenter you have built. Or why you’d want your full-stack export to be specific to applications, rather than being open-ended for general-purpose systems which can interface with importers’ proprietary structures.

It’s similarly unclear how to square the approach with various AI developers’ ‘AI for countries’ efforts. Is brokering an OpenAI Stargate deal, or even a full Google stack including in-house silicon within the scope of export promotion? It might be, but what’s the government’s value add, then? It couldn’t be coordination as gestured at in the EO, because Stargates themselves have mostly been coordinated and integrated packages – so is subsidising AI developers’ existing platforms through diplomacy or financing in scope? Perhaps export promotion is supposed to only work where Stargate-like projects do not, such as in countries too small to warrant major developers’ attention – but to focus a purported strategic leverage framework only in the smallest markets seems puzzling as well. There is much left to clarify here.

Many of these questions reduce to a core tension between three desiderata here that sellers will have to figure out. An ideal export stack, from the ideas laid out in the executive order and the notion of maximising global market share, would have to satisfy the following desiderata:

Full-stack exports. Be integrated or cross-cutting enough to count as ‘full stack’ in the sense of the flywheel effect described by senior White House officials.

Make big sales today. Satisfy current real demand by importing countries, which are often irrationally focused on fake sovereignty or training capacity due to deep-running misconceptions about their own position in the AI race.

Secure loyal customers. Respond to actual, future demand of the importers. The US wants the exported solution to remain attractive even once buyers improve their strategic understanding, so that the export captures enduring market share, leads to further exports, and can’t be undercut by a Chinese competitor that offers a better fit to future needs later on.

These ideas are sometimes in tension. The two most striking problems are the mismatch between 1 and 2 as well as 2 and 3: Insofar as it exists, current real demand from countries on AI aims mostly at fake sovereignty, which importers often believe to be different from full-stack imports. Simply selling them what they want right now, however, is also not a good solution: If you satisfy a demand that will inevitably change soon, you don’t win the enduring market share you’re looking for. The US edge is that it gets to sell today, but the market for useful full-stack exports today is still small. What to do?

Toward a Solution

To square that circle, the US government might have no choice but to compromise a bit: It needs to focus its exporting efforts on a stack that gets in on the current level of demand, but continues to capture the market at future levels of awareness. A central design goal should hence be closing the awareness gap.

Export Design

Reconsider including the application layer. This is where some of the most significant mismatches between supply and demand occur. Many countries lack a clear understanding of the applications they need at this moment, including how to integrate AI into their education systems, what military applications, if any, they’re interested in, and so on. Any deal that prescribes instead of supports an application layer in detail risks being unresponsive to future preferences. Flexibility provided by hosting general-purpose systems enhances the sales pitch and increases the likelihood of lock-in. Concerns about diminishing the flywheel effect should not stop you: as long as the entire rest of the stack is US-built, any application layer on top will likely be linked to the US ecosystem and contribute to the synergies the administration cares about.

Provide importers with some notion of sovereignty that enables meaningful freedom within the US ecosystem, but no breakout to Chinese solutions. Imported sovereignty is primarily a problem for US strategy insofar as it creates the future option to break away from the US stack. The tempting solution is to include contractual obligations not to switch to Chinese solutions, like in the UAE deal. But this is exactly what might set off the diplomatic risk of backfiring: If the promotion framework looks too much like it’s supposed to create path dependencies, sovereignty-minded buyers might be out. It’s an important mechanism especially given untrustworthy buyers, but should not be overused in interfacing with allies that could take offense and grow cautious.

So, any approach that frees up any capacity for importers to command is very helpful; though I’m less certain on how to get this right. Perhaps they can be freed up to repurpose parts of the infrastructure stack after a couple of years of exclusive use, when it’s no longer state of the art. You could also consider allowing importers to use the hardware stack to run open-source models instead. If the US is optimistic in its commitment to service top-tier open source models, and has reason to believe it can run them particularly efficiently so that it’ll be more attractive for importers to run US rather than Chinese OS, it should seriously consider opening the stack up at the AI system layer with some delay. I believe that would contribute greatly to a perceived sense of sovereignty, which might be the most important part of the diplomatic puzzle to get right.Spend some money. Equipping your favorite vehicle to outright fund promotion would be the most obvious win. That would happen perhaps most obviously through the revolving fund at DFC, and maybe further scaling up EXIM’s appropriations — though there is some lack of precedent regarding the latter’s extensive application to software. But more importantly, the political economy for outright subsidies is difficult, and appropriations are hard to come by. Beyond direct subsidies, you might provide extensive financial derisking, which aligns positively with the AI private sector’s general interest in diversifying away from a small number of markets. Enabling consortia to provide cheaper import deals doesn’t only reduce the threshold for locking in deals now, it’ll also be important to compete with any potential future Chinese export product. Taking on the financial cost via favourable insurance is a little bit more politically feasible right now. And if the administration feels it has good reason to believe in its model of how AI will go, the risk should be manageable.

Realistically, this might be a two-step process, where more extensive appropriations could be secured only for the 2027 fiscal year. But starting out with underpowered funding is risky even if that’s the plan: without some keystone projects to show for, Congress might not take too kindly to the idea to expand funding for export promotion in the future. If the promotion framework starts out with too little funding, spread too thin over too many projects, it might never get off the ground. To the extent that the two-step process is unavoidable, it might be well-advised to stick to very few projects in the first year to gather solid proof of concept for budgetary expansions down the line.

Demand Shaping

A second leg of a successful US strategy would be to contribute to shaping importers’ demand. That’s a thin line to walk. On one hand, the US has a wealth of private and government insight into the trajectory and capabilities of AI, the sharing of which can be useful. In the absence of sufficient capacities at the State Department, in particular following recent cuts, the capacity to spread this awareness needs to be created elsewhere – lead perhaps by OSTP, but tapping into the broader American AI ecosystem: A large-scale effort to have trustworthy leaders in technology and technology policy interface with sympathetic elements in importing countries to create some awareness of the upsides of AI imports seems within scope for successful export promotions. This would be even more effective if the US could create a snowballing effect from recruiting representatives from early importing countries to the rest of their respective regions.

On the other hand, it will be very difficult for the US to credibly communicate anything to importers. The first reason is because the related objective of export promotion is so clear: as soon as the US has made it officially its policy to boost the export of chips and models, it has a business interest in getting these deals through, which will cast some doubt on any opinionated campaign. The second is that based on recent foreign policy, the US is already facing some suspicion of self-interested negotiation in more general terms. How to get around this? I suspect it differs regionally.

Especially where political leaders are not sympathetic to the US’ foreign policy, there might be value in playing the diplomacy offensive via the private sector: in most less-clued-in middle powers, the private sector is much more anxious and ready to get AI right, and can serve as a more trustworthy internal advocate. Keeping the AI export conversation far enough away from the remainder of the trade policy conversation would presumably be very helpful in a similar vein. The administration’s close ties to business leaders are an untapped resource for getting export promotion right.

Importers Step Up?

Third, obviously, importers should do a lot more to get all this right. I focus on the US in most of this piece because I think the fundamental issue in much of this is importers’ lack of serious thinking on this matter. In an ideal world, they’d pick up the slack and proactively approach the US with well thought-out ideas for what they want to import within the scope of the EO. But alas – they are not. Still, for some minimal ideas that might resonate with prospective importers:

Be fast: as long as the US is still out for early keystone successes, terms are likely to be somewhat better. Relatedly, getting in on the earliest instances of the promotion plan, before a huge SOP has been developed, probably gives you slightly more leverage around the specific contents of the deal.

Be specific: The more ideas you have around your prospective demand regarding what a full-stack import should look like, the more likely you are to be prioritised in negotiations. Given limited negotiation resources on the side of the US government, I’d expect ‘easy-going’ importers to receive some privileged treatment. One way to be an easy-going importer without compromising on a lot of the substance is to be able to reach a deal quickly – which is only ever going to happen if you don’t have to figure out what you even want in the process.

Don’t chase the sovereignty spectre. Most countries in the world will not reach a meaningful extent of AI sovereignty. The perhaps more relevant measure of your sovereignty as it relates to AI is your ability to retain economic and strategic leverage from other fields to ensure that you remain an attractive export partner for AI. This is the forcing function I mentioned at the top: Once countries realise they’ll be net importers of AI, that’ll force them to consider how to structure their economies and strategic alliances around that fact. This has been a long time coming – realising it early helps get the importing part right, too.

Outlook

I really do believe getting US exports and their promotion right is both a crucial part of US strategy and one of the very few tractable policy projects to meaningfully improve international AI outcomes. At a rare current moment, there is concrete policy action on the table, and a measure of political support behind the directionally correct trend. But for many reasons, it’s an uphill battle. On both sides of the import-export-relationship, those in the know have to make sure demand and supply don’t drift too far apart. We should really get this right.