AI, Jobs, and the Rest of the World

No one but America has the leverage to get AI labor policy right

Isma’il Pasha was sure he had cracked the code of policy arbitrage. In 1863, he endeavoured to modernize Egypt’s failing economy and military through massive Europeanisation: schools and railways, boulevards and line infantry. Without a European-scale tax base, the plan quickly collapsed: Egypt was placed under humiliating external supervision of its debtors, and Isma’il was quickly deposed.

Serious people in America are thinking more and more about reasonable research to assess AI labor market impacts, and reasonable policy to shape them. This is very good news for the 350 million citizens of the US, and I feel tentatively optimistic about their AI and jobs prospects. However, most of this research and all policy ideas exclusively work in America — and could often make things for other countries worse. International policymakers’ default of observing US trends and decisions on AI and modeling approaches in response is set up to fail. They face the kind of rough awakening that befell poor Isma’il.

That is because basically any proposal on AI & jobs that hinges either on regulation or redistribution works entirely differently in the rest of the world than in the US: Only the US retains an enduring fiscal base in an AI age; only the US commands substantial regulatory leverage over AI development. As a result, I think one of the most likely futures holds a US economy with high employment of AI-augmented workers, while many other global labor markets are caught off guard and severely disrupted by US-run AI agents.

This is a particularly big problem because it messes with AI policy’s implicit arrangement that the US is the policy research lab for the world. Clued-in policymakers anywhere are looking to the US for trends, ideas, and canaries in the coalmine of AI and jobs, shaping their responses based on the trends they observe. And among researchers and advocates, the best and brightest flock to the US, identifying correctly that the most important jurisdiction offers the largest lever to pull. In exchange, they figure out what works best to make AI go well anywhere, report back to the provinces, and the world learns to get all this right. This all dramatically breaks down in this specific case: Any policymaker who looks to the US to learn what to do about AI & jobs is doomed to fail. No ideas we might come up with on labor policy translate well to any other jurisdiction.

This breaks down into three reasons: Most middle powers are more exposed to disruption, have less regulatory leverage, and cannot expect an influx of tax revenue from AI progress. If there’s any way out, it runs through getting exports, imports and strategic leverage right.

Greater Exposure

First, I think there are good reasons to believe that disruptive job effects from AI are likely to hit non-US countries earlier and harder. Two important predictors for this trend are the degree of individual augmentation and economy-wide AI literacy.

By degree of individual augmentation, I mean to say: A labor force that has adopted helpful AI technologies to boost its output is less susceptible to outright displacement by AI agents. The efficiency gaps between augmented workers and agents are much smaller, making the lump investment of changing gears to agents much less attractive. This is a simplified version of the story – more effective augmented workers reduce a company’s demand for new hires, for instance. But still, I maintain that in a growing economy, it makes a big difference if a new company pays for 10 AI agents or hires 10 AI-augmented employees. I think the odds are good that America is set to lead on AI adoption, and therefore will have a more agent-resistant workforce in due time. This is mostly for two reasons: because the US has by-default access and very high awareness of the tech itself; and because its policy environment is much more on the ball when it comes to enabling AI uptake – the AI Action Plan in particular reads like a dream come true for fans of augmentation-boosting policy.

By general AI literacy, I mean how quickly the overall economy adopts AI, not as a matter of individual users using AI, but through identifying opportunities for new businesses made possible by advanced AI capabilities. Even if AI agents disrupt your existing labor market, there will be ample time for humans to find employment through novel applications of these agents – at least for a time. As with past technological revolutions, these jobs will be created where entrepreneurs come up with ideas to effectively deploy these new capabilities. I’m likewise optimistic about America’s comparative ability here, both for the reasons above and because of America’s astonishingly impressive track record regarding tech startups in the last two decades. For all the reasons that everyone building a start-up wants to move to America, I suspect that many jobs created from novel deployment of AI capabilities will be created in the US.

What about task profiles? Is the US perhaps more exposed because of its greater share of white collar workers? I think this is a reasonable claim on the margins, but I’m unsure it matters a great deal. High-level, the US does not actually have a much larger share of white-collar or information workers than many other major economies, and it makes up for it by having higher-skilled white collar workers, who seem somewhat hard to displace and easier to augment. Beyond such high-level distinctions, I don’t feel we know enough about sector-by-sector displacement to make strong statements about economies’ respective exposure based on their makeup.

Everywhere in the world, job profiles will shift and some jobs will be lost as a result of AI deployment, in what I’ve described before as ‘phase one’ of AI job disruption. I’ve said that the employment and growth effects of that phase would be neutral to positive, but I think this headline trend will conceal stark regional differences. The US is ahead of the field on two important countervailing trends: augmenting workers to compete with agents, and creating jobs through using AI. As a result, the natural trend of AI-driven labor displacements will hit earlier and harder in the least prepared places elsewhere in the world. How might they react? I’ve written before that, once disruption happens, two solutions seem possible and feasible in the abstract. First, you might introduce social and labor policy to cushion the effects of unemployment and redeploy your workforce; and second, you might want to directly address AI systems and their impacts through policy. The US is in principle empowered to do either, but most other countries will struggle with this.

No Taxable Bases

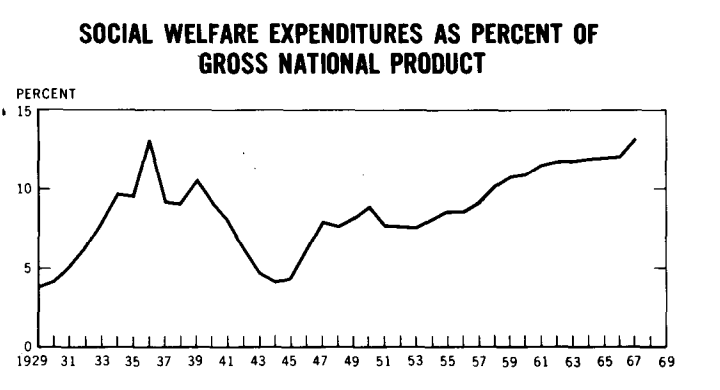

Second, the US will have enough tax revenue for social welfare interventions, but many other countries won’t. Many policy researchers’ favorite proposals cost a lot of money. Most obviously, any policy of redistribution - whether it’s money, GPUs, or something else - requires getting that money from somewhere. Enabling widespread retraining and redeployment of your workforce is likewise costly; and smoothing over the broader implications of rural-urban shifts, intermediary unemployment, readjusting education, and whatnot is of course also expensive. Social policy enthusiasts like to point to the New Deal as the prime example of policy-supported economic transformation gone well. Perhaps it was – but just look at how expensive it was:

If you have ambitious plans for labor policy, you’ll need a lot of money. If you ask where you’ll get that money nowadays, a frequent response is: ‘AI-driven economic growth will be very high, so taxation revenue will increase and enable expansive social policy’. On a very high level, that’s true: the total amount of global revenue will dramatically increase. However, two effects make it unlikely that most countries can tax most of that revenue: the revenue moves both within and between economies.

Inter-Economic Shifts: Revenue moves to the US

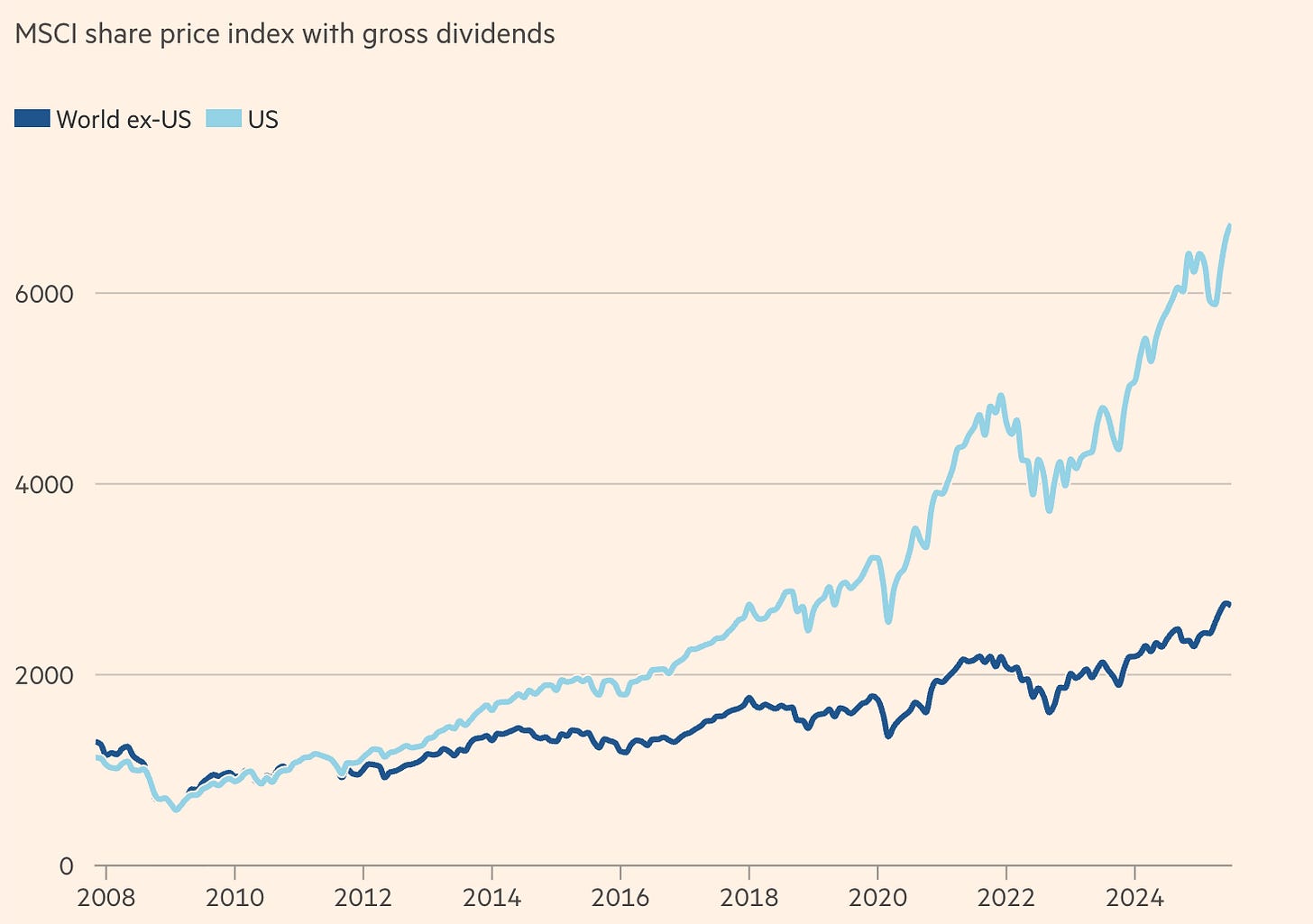

Revenue moves between economies, mostly to the US, because that is where most of the growth is likely to manifest. You’d expect an ‘AI revolution’ to make AI companies rich first and foremost - and the best AI companies are in America. Some people disagree with that intuitive drive, arguing that the commodification of AI models could stave off revenue agglomeration on the developers’ side. I think this argument is true for general AI models, but likely much less true for the kinds of AI agents we would expect to be required for big job market effects. The path to highly capable agents seems to run through constructing sophisticated, bespoke reinforcement learning environments that make them excel at specific task profiles – and AI developers are taking different approaches to training their respective models. I find it hard to believe that the resulting suite of agent products would be as easily commoditised as AI models, which are admittedly all very similar.

But even if agents were commoditised, I don’t think it follows that growth distributes equitably. Another candidate for capturing most revenue is AI infrastructure: semiconductor companies and cloud computing providers. Given the massive shortages in global compute supply and the fact that they might well last in the face of inference-hungry AI agents, I expect much AI-driven growth to accumulate around AI infrastructure. This again means an outflow to America, where the leading chip company sits, and which favours an export strategy that retains US market share.

Intra-Economic Shifts: Income to Corporate Tax

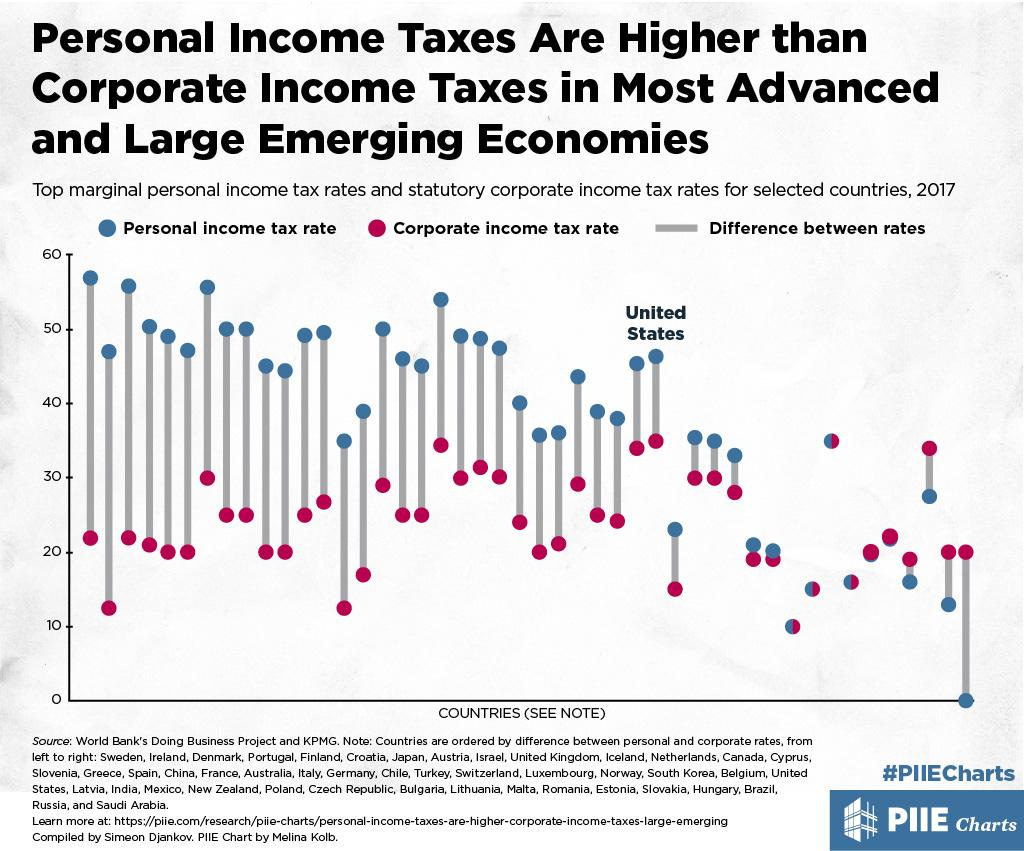

And even the portion of revenue that does not move to the US will not necessarily remain easily taxable. Within economies, revenue might shift from labor to corporations: As economic value is provided much less through the labor of individual workers and therefore taxed through income taxes; and more through AI agents, which are software products ultimately taxed at corporate tax rates. However, corporate taxes are generally much lower than income taxes, so the shift hurts overall revenue. Net growth can still lead to a net loss in tax revenue because less is captured by taxes. This is hard to fix because corporate taxes are also much more difficult to adjust – even small changes can have big effects on economies, stock markets, investments, and future economic activity. To make matters worse, a corporate tax rate hike would also hit any business that doesn’t use AI well, likely creating further economic disruption. Could you circumvent that with tech-specific taxes? No, for reasons spelled out further below.

The result is that the kind of ambitious social policy agenda that could successfully address labor market effects depends on countries benefiting from economic growth driven by AI. This, however, is far from guaranteed, and I expect many countries to be left at a net loss in tax revenue at a time when they’d want to expand labor policy and safety nets. Can regulation save the day? I think not:

No Regulatory Leverage

Third, only the US has real regulatory leverage over AI developers and the circumstances of deployment. If your economy is not equipped to deal with AI disruption, and your fiscal setup is not equipped to address the fallout, you might want to stop what’s happening through regulation. There are some politically obvious mechanisms here: you can require ‘humans in the loop’ in an attempt to save human jobs. You can regulate AI out of sensitive applications to artificially retain human jobs. You can just pass general regulation on AI systems that makes them harder to deploy, harder to use, more burdensome to make the swap – and thereby save jobs by slowing diffusion. Alternatively, you can use regulation as a pretext to collect fines, thereby creating a revenue stream in lieu of taxation – a practice some have accused the EU of pursuing with its digital governance.

But can you, really? If you’re the US, of course you can – in fact, you might, which has a lot of intelligent observers worried. But if you’re anyone else, passing decelerating AI regulation will become increasingly difficult for two reasons.

The most important reason is that decelerating regulation risks economic and strategic repercussions. As AI becomes more important, not using AI becomes less of an option. That makes AI different from past economic trends that you could just choose to skip. If you don’t have a big cut of the global tech industry today, that’s already somewhat bad – the growing divergence between European and American GDP is a testament to that fact. But most other parts of the economy were fine: the gap in tech did not mean a gap in the productivity of other economic sectors. But AI is different altogether: I suspect AI will become an important part of most economic activity, and so being behind on AI means you’re behind on most of your economic contributions. If you regulate frontier AI out of your economy to stave off labor effects, you might just regulate your economy out of global competitiveness.

A related effect is that unilateral decelerating regulation exacerbates labor market risks down the road. If you stop the diffusion of AI systems throughout your economy now, your workforce will be less augmented and less efficient in the long run. That makes it more susceptible to being outcompeted by autonomous agents or by augmented workforces later on – and you can’t forcibly keep your economy from eventually gravitating toward efficient global optima in the long run.

The second, slightly more contingent effect is US pressure not to regulate. The current administration, in particular, has made it very clear that it will not tolerate extensive foreign regulation of its AI developers. It’s willing to defend this perspective through leverage in other areas, for example, in trade policy or with regard to military and intelligence support. And I suspect it will defend this perspective just as ferociously through leveraging AI access, come time. Currently, the US is poised to dominate the global intelligence flow–with US-built models hosted on US-built data centers run by US companies. Continued access to frontier capabilities will depend on remaining in America’s good graces, and regulating its AI developers is a surefire way to endanger that in the current political climate.

This might change again once administrations change toward a more internationalist view – but who’s to say when that will be? And even a future Democratic administration might be reluctant to rescind US pressure against regulation: in the face of geopolitical competition, actively taking a step to allow decelerating external regulation won’t seem like a wise policy or effective politics. Countries the world over are still holding out some hope of returning to a pre-2016 US relationship. On AI (and most other things), I think it’s not happening.

The upshot is that you can’t regulate your way out of AI disruption unless you’re willing to accept economic disadvantages and risk strategic retaliation. At this point in the argument, inevitably someone will tell me ‘that’s why Europe has to get serious this time around’. On strategic terms, I agree – on practical terms, please check in on how that’s going.

The Role of US Policy

Instead of placing hope in unserious actors getting serious about AI, you might instead hope that the US government does something to its AI developers to help the middle powers – either on purpose or by accident.

The US is very unlikely to choose to help middle powers as the effects of widespread AI deployment rip through their labor markets. Some policy research suggests US companies should be taxed to fund not only welfare spending in the US, but globally – for reasons that should be obvious from the administration’s general policies, I don’t see that happening anytime soon. The US won’t be of much help in the revenue problem, and for good economic reason: If US companies build a product that outcompetes foreign workers, these foreign workers are not America’s responsibility any more than displaced auto workers in Detroit were the world’s responsibility.

I also don’t see the US intervening in AI development for the sake of others, i.e., because AI is destabilising foreign labor markets. Quite the opposite: If the rest of the world is hit first, the US might be particularly disincentivised to do anything about AI labor disruption. Quite quickly, the story could become that AI is helping effectively ‘reshore’ jobs: White-collar jobs that have been lost to the US economy are returning – not to be carried out by US workers, but by US AI agents at least, promising tax revenue and a sense of retributive justice.

On policy, if things get bad enough in America, could there be a positive spillover from US interventions that also helps the rest of the world? The US will be interested in solving its own labor market problems, and would probably intervene if disruption were to mount. As argued above, AI might just go fairly well for the US job market specifically. But even if it doesn’t, it’s far from certain that US-specific policy solutions would actually help the rest of the world. The only scenario in which that might be true is if the US policy response is slowing down AI development – not diffusion – to reduce job market effects. But that seems unlikely for geopolitical reasons: The administration is still committed to seeing through a technological competition with China, and hitting development with decelerating policy interventions is a surefire way to lose that. They’ll try other solutions first, whether that’s welfare, retraining, or slowing domestic diffusion – none of which help anyone outside the US.

There is one silver lining: The US is aiming to execute an ambitious export promotion strategy that could close the widening deployment gaps that have motivated my argument. More on the promise and pitfalls of this proposed plan will feature in this publication soon.

But for now, in general terms, the lesson remains: Not only can you not rely on US policy to fix your problem; from the administration’s perspective, exchanging foreign jobs for US agent revenue might often be a feature, not a bug.

Facing the Music

What's the key takeaway from all this? First, I’d really like for the AI policy ecosystem to take this question much, much more seriously. My sense is that no one is on the ball on the specific issue of job disruption in non-US labor markets. That’s true for many areas of AI policy as they relate to middle powers – but it’s a much bigger issue here, because the solutions spill over so much less. I regret to leave you with as much of a non-answer, but I think the challenge is profound enough to warrant an unsatisfying post; solving it will require quite a bit more firepower than this publication can provide. I do have some starting thoughts:

My general suspicion is that this conversation collapses to a geostrategic question: getting this right might be much less about finding a silver bullet labor policy, and much more about retaining leverage and participation in frontier AI. That’s a broader and trickier policy ask. It’s currently not addressed with enough urgency by most middle powers - but I think framing the politically salient labor issue in terms of these strategic terms could provide another reason to change that. Policymakers famously care about jobs quite a lot, and seem generally more willing to believe that job disruption from AI is likely than they are to believe some of the other grand theories of big AI impacts. Pointing out to them that their economies are exposed to AI job disruption should lend some further urgency to the underlying strategic questions and motivate a more decisive response.

What would that look like if it were effective? As I’ve outlined a couple of months ago (and desperately need to comprehensively update), it has a lot to do with finding points of leverage within an AI-driven world; either up or down the supply chain. If momentary high leverage can be spun into an enduring share in AI-driven growth, this could plausibly solve the problem. For instance, by selling valuable data in exchange for an enduring share in AI companies’ profits, you might be able to pay for your policy plans. Alternatively, providing necessary manufacturing contributions to an American-led alliance might pay well enough and require a sufficient workforce to keep up with the disruption. Solutions here will inevitably vary between countries to an extent that makes a sweeping response unfeasible.

The policy conversation on AI and labor is currently mostly happening in the US. I think it’s important for middle powers to realise that this conversation won’t help them much; and for US-focused policy researchers to realise that many of their proposals are leaving some billions of exposed workers unaccounted for. If the rest of the world follows the US on the AI labor conversation, it will be led astray.