The Awareness Gap

AI middle powers underestimate the pace of progress. Global volatility could follow.

When the Goths crossed the Danube in 376 and devastated the eastern provinces, Roman leadership was not very concerned. The western capital’s walls held, and the Goths were far away. Only when the inflow of fealty, recruits and goods from the ruined provinces dried up did leadership realise how much the safety of the empire had depended on its periphery – too late to stop the sack of Rome in 410.

Everyone knows that international AI policy is a tale of two cities. National ambition and international proliferation is framed through the lens of the two great AI powers, the US and China, and their fierce competition for technological supremacy. China and the US hold far more compute, talent and state capacity to compete in an AI race than the rest of the world. It seems obvious they’ll run the show by controlling the flow of computing resources and AI models. As a result, many observers predict a bipolar economic order shaped by diffusion controls and vying spheres of influence between great AI powers. On that view, focus on the US and China seems warranted: getting the hegemons’ policies right seems to mean getting the overall order right.

But there’s a problem to this story of smooth sailing toward the bipolar AI world: Other advanced economies might not play their part. This is due to an awarenesss gap: AI middle powers1 lack awareness of the scope and speed of AI progress, and are messing up their geopolitical positions as a result. The ensuing misplays could drive middle powers into uneasy dependencies on US adversaries, incentivise them to hinder global AI progress, and make already volatile regional powers destitute and desperate. AI’s promise makes for plenty of internationally net-positive solutions that would reduce this volatility, from middle power coordination to equitable diffusion rules to strategic trades with great AI powers – many productive policy conversations could be had. But as long as middle powers remain in ignorance or denial, mutually satisfactory AI geopolitics remains out of reach due to lack of political motivation.

Minding the Gap

It’s first worth clarifying why one should care about this problem. Readers might think I’m simply lamenting an impending and unavoidable reordering of the global economy, as it happens time and time again. I disagree - both because these reorderings have repeatedly been hotbeds for geopolitical risks, and because this specific reordering would go so fast and forceful that it would make for particularly high volatility. The key question is: Where does a middle power go when it has missed out on a sovereign strategy to deploy and leverage AI? Three concerning paths come to mind.

First, previously-allied middle powers might be vulnerable to ‘help’ from US adversaries. One striking lesson from the diplomatic inroads made by the Chinese Belt-and-Road initiative is that countries with acute infrastructural demands are willing to accept ruinous terms to fulfil them if necessary. These countries would have had the chance to hire US firms, to comply with WTO standards, to draw IMF support – but these standards were too demanding to be politically feasible. And after things got more dire, China swooped in with enticing offers of short-term help at the cost of long-term dependency. The BRI has sometimes been misrepresented as a great geopolitical plan. Following my argument does not require making that mistake – all you need to believe is that China is quite savvy at bringing together dire foreign demand for infrastructure and its own rapid buildout capabilities.

It’s not difficult to see how that strategy might be reproduced on AI: Middle powers are too unaware to secure compute and API access, buy GPUs, or build out datacenters themselves. When demand for AI deployment becomes painfully obvious, China offers to deploy Chinese-built AI infrastructure, at the price of geopolitical and economic lock-in into Chinese ecosystems. That prospect leaves no pleasant prospects to middle powers – and it poses a huge geopolitical liability for a United States gearing up for great power competition.

Second, middle powers might be incentivised to try and slow down AI progress. If you’re holding the wrong cards for an AI-driven world economy, your best bet might be to work against the ongoing transformation. That’s admittedly tricky to do given how much development is concentrated in the US and China, but there are some levers still: First, the compute supply chain is long and vulnerable, and single links could be leveraged by determined middle powers. Export controls on ASML machinery might not be in the strategic economic interest of Netherlands or the EU, but still make for an appealing desperation move. Second, global regulation provides some leverage. If large parts of the left-behind world introduce regulatory regimens that meaningfully slow down AI diffusion and revenue, that still leaves the great powers with their domestic market – which might be enough to sustain further progress, but surely invite less ambitious investment than a global transformation would. And third, desperation might just drive some already-combative nations to the brink – to sanction labs, sabotage data centers, and backlash violently against AI progress.

Third, middle power economies and welfare systems might rapidly crumble. There has recently been some domestic discussion in the US about the impact of AI job disruptions on society and the economy at large. In the US, the worst of such effects can be cushioned: the US can tax AI developers, receives AI diffusion and the resulting deflationary effects by default, and already has decisionmakers directionally aware of the challenge. There are still important parts to figure out, but the hard backstop for US politics still seems to be transfer payments and subsidised sinecure jobs. But in middle powers, AI-driven disruption of economic paradigms can be explosive. Middle powers can’t tax AI developers quite as easily; and they also don’t receive an AI rollout by default. If there is a middle power that manages to bleed its automatable, internationally fungible jobs without receiving the benefits of widespread AI adoption, it could end up in a genuinely dire state: without the state revenue to fund welfare programs to smooth the disruption, and without the technical progress to offset the resulting loss in general welfare.

I don’t want to find out what happens when influential middle powers get derailed like that. History offers some frightening lessons for what happens when national egos get bruised by rapid descents, from recent Russian aggressions to the turn of the Weimar Republic into Nazi Germany. And that is just the national level; on an individual level, collapsing prospects have long motivated desperate action, from rising populist sentiment to deterioration of public order and mass-scale migration – all factors of outsized volatility at a critical moment in technical progress.

Next to all these effects, I will also say: Most people do not live in the US or in China. The extent to which the promise of AI is fulfilled is greatly dependent on how readily its benefits can be rolled out to the world at large; a great part of which comprises citizens of middle powers. Having AI go well is also a story of having it go well for these countries, and when they lack awareness, the odds of that happening drop dramatically.

So why is the awareness gap so crucial to middle powers’ likely falling behind?

The Diffusion Framework

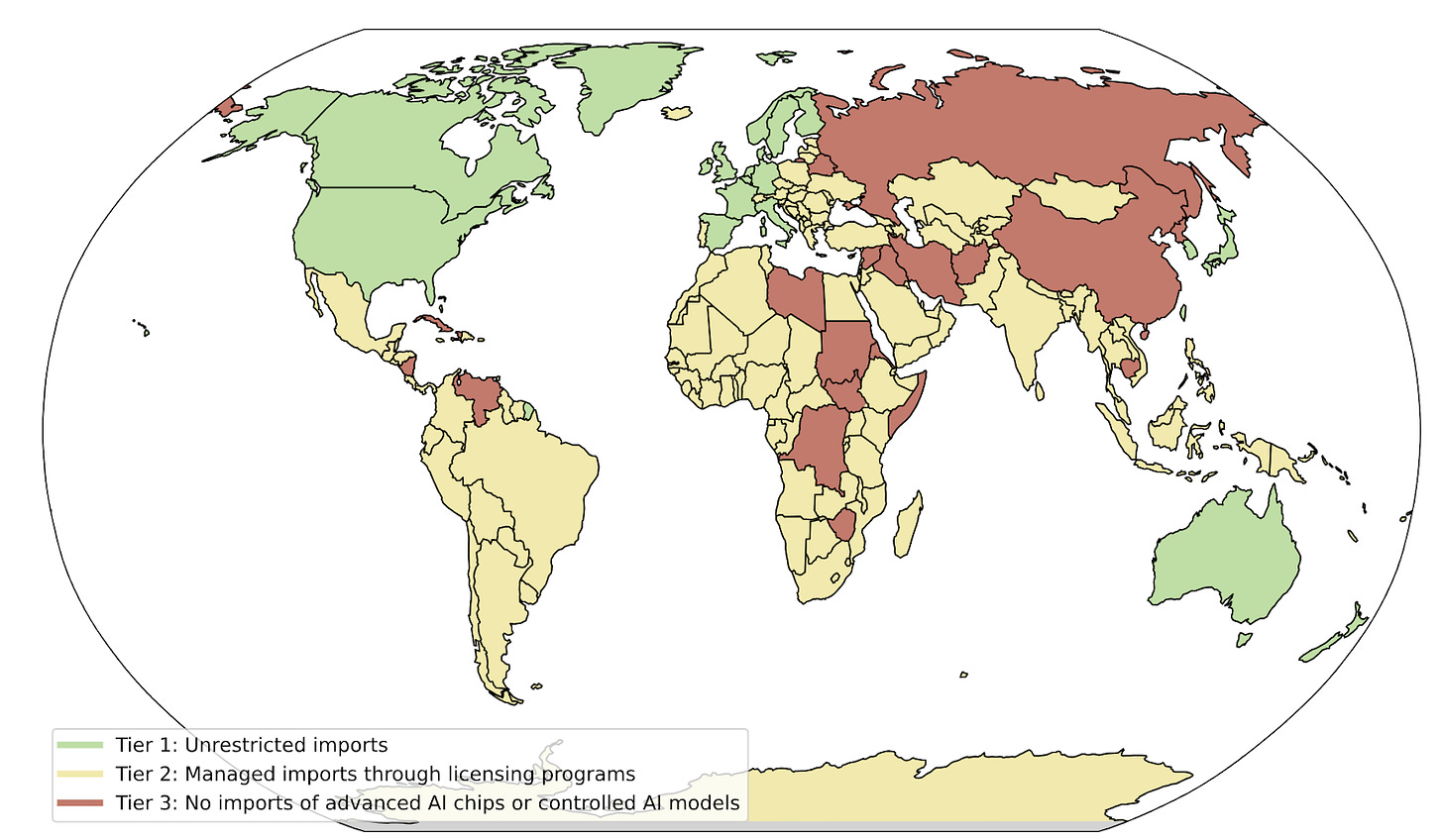

The first flashpoint of this problem occurred around the Biden administration’s diffusion framework regarding advanced chips needed to develop and deploy AI (‘compute’). That framework categorised countries into one of three tiers, according to which they’d be subject to export limitations. To an informed observer with a clear-eyed view of the technical trajectory, the tier you were in would make a huge difference: Any ambitions you might have to scale up development or deployment at the technical frontier would be entirely dependent on importing compute, and thus on the extent of US export restrictions. One would think that the diffusion framework would have prompted international discussion, negotiation, outrage – anything. It did not: its stipulations were communicated at fairly low levels and drew no meaningful public reaction. For a country like India, being sorted into tier 2 spells peril for any plans to ramp up computing infrastructure; for an organisation like the European union, being divided into different tiers endangers any of the ambitious joint projects that would run across diffusion differences. Despite this fact, the diffusion framework did not receive major attention at the highest political levels in the affected countries - not even giving them a chance to leverage and negotiate around access, exceptions or higher-tier perspectives.

Since then, the Trump administration has rescinded the diffusion framework. Its acute motivation was an export deal with the UAE that would not have been possible under the old framework. A slightly more overarching reason might be underlying disagreements with the Biden-era view of AI strategy: whereas the Biden administration might have thought ‘winning the AI race’ would mean leveraging hard constraints on exports, parts of the Trump administration might rather believe ‘winning’ is about generating maximal revenue and proliferation of US-built AI through more permissive export rules. Even still, diffusion as such does not seem dead altogether; there will be a follow-up rule to the scrapped framework. The administration still seems to be in the process of designing that rule; for instance, reports point out one recent comment made by Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, who mentioned in passing that exports might generally be more readily permitted if US firms ran the data centers in which exported compute ends up.

My sense is that, puzzlingly, most AI middle powers are not following that discussion very closely. The UAE stand out in contrast all the more – they have correctly identified their advantage in an AI world, which is enough money to buy GPUs and enough energy to run them, and have accordingly negotiated the US into changing the diffusion rules so they could leverage these strengths. That is, to date, the only semi-public feat of serious AI geopolitics by a middle power. That is a stunning indictment of most advanced economies.

A new diffusion framework is an opportunity for some of the previous tier-2/tier-3 countries as much as it’s a threat to previous tier-1 countries. For instance, it seems difficult to imagine how a European AI Gigafactory initiative could be successful if the diffusion rules either placed export limits on the necessary H100 chips or required US datacenter operators. And if a middle power’s favoured national strategy relies heavily on industrial applications or model uses heavy on running inference at home – such as it might be imaginable for some former manufacturing powerhouses – being in tier 2 or tier 1 makes a dramatic difference. If they were aware, a lot of middle powers could get this moment right, negotiate according to strategic priorities, and set up for success. But because they lack this very awareness, they are rolling the dice on a critical element of their strategic and economic future. Already today, middle powers are falling short of their potential to participate in AI progress due to their drastic lack of awareness.

Upcoming Sequels

This is likely to get worse. US diffusion restrictions will not be the last episode of rapid AI progress that requires government foresight to navigate.

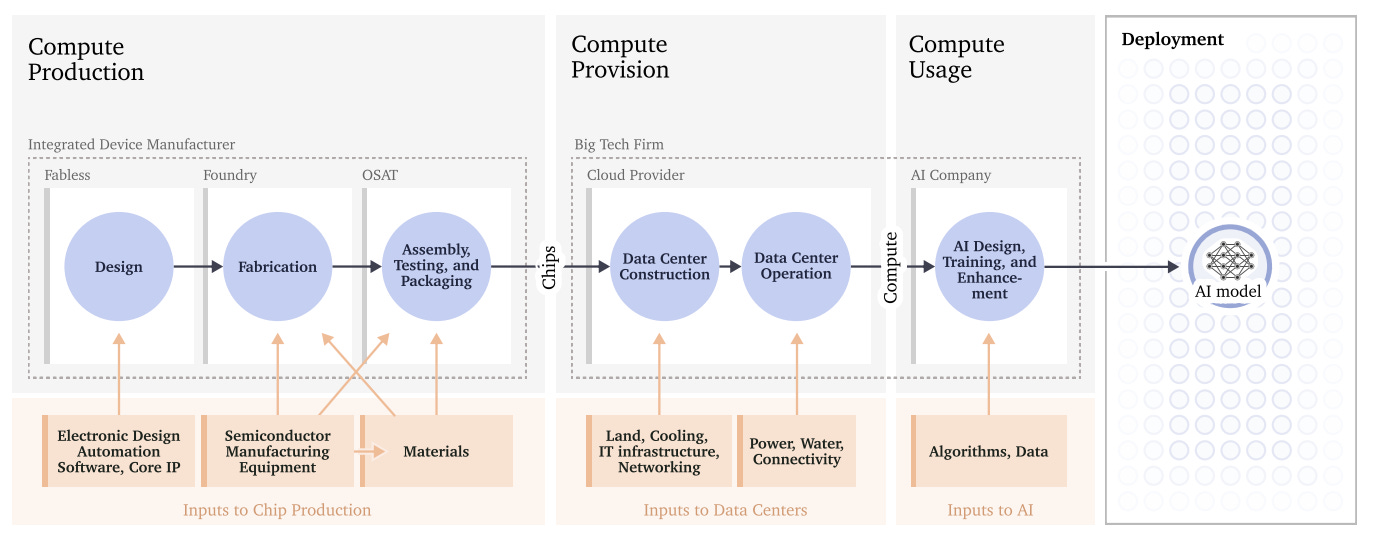

First, further instances of diffusion control might well occur. Two obvious next steps are controls on where frontier weights may be hosted and exported, and controls on who may access frontier models through APIs. The rescinded diffusion framework already included some related provisions for foreign compute, but had been mostly perceived as a compute-focused policy tool – future policies might put greater direct emphasis on model diffusion as such. Weight export restrictions are easily explained as a matter of AI security, and have already been suggested in multiple influential pieces: You can’t just let your weights sit on any unsecured datacenter if you have good reason to believe adversaries might have an incentive to steal them, either to gain insights into your systems or to use them for malicious applications that are otherwise prevented. So middle powers might be restricted from access to frontier weights – and with it, from sovereign capacity to run them and from ability to fine-tune them for economically and strategically important use cases. Restricting API access is more brazen of a foreign policy lever, but a forceful one – should an economic AI order emerge in which much of the world runs on US APIs in much the same way that much mundane software works today, the US could exact enormous control by attaching continued access to conditions.

I will say that the current administration seems not very inclined to go down this stricter diffusion route just yet – but others have written at length about the incentives to the contrary, especially as security becomes more important, espionage and clandestine distillation become greater threats, and misuse risks rise. Between such incentives and sometimes volatile coalitionary tides within the administration, I would not feel comfortable to bet on no further controls if I was a middle power.

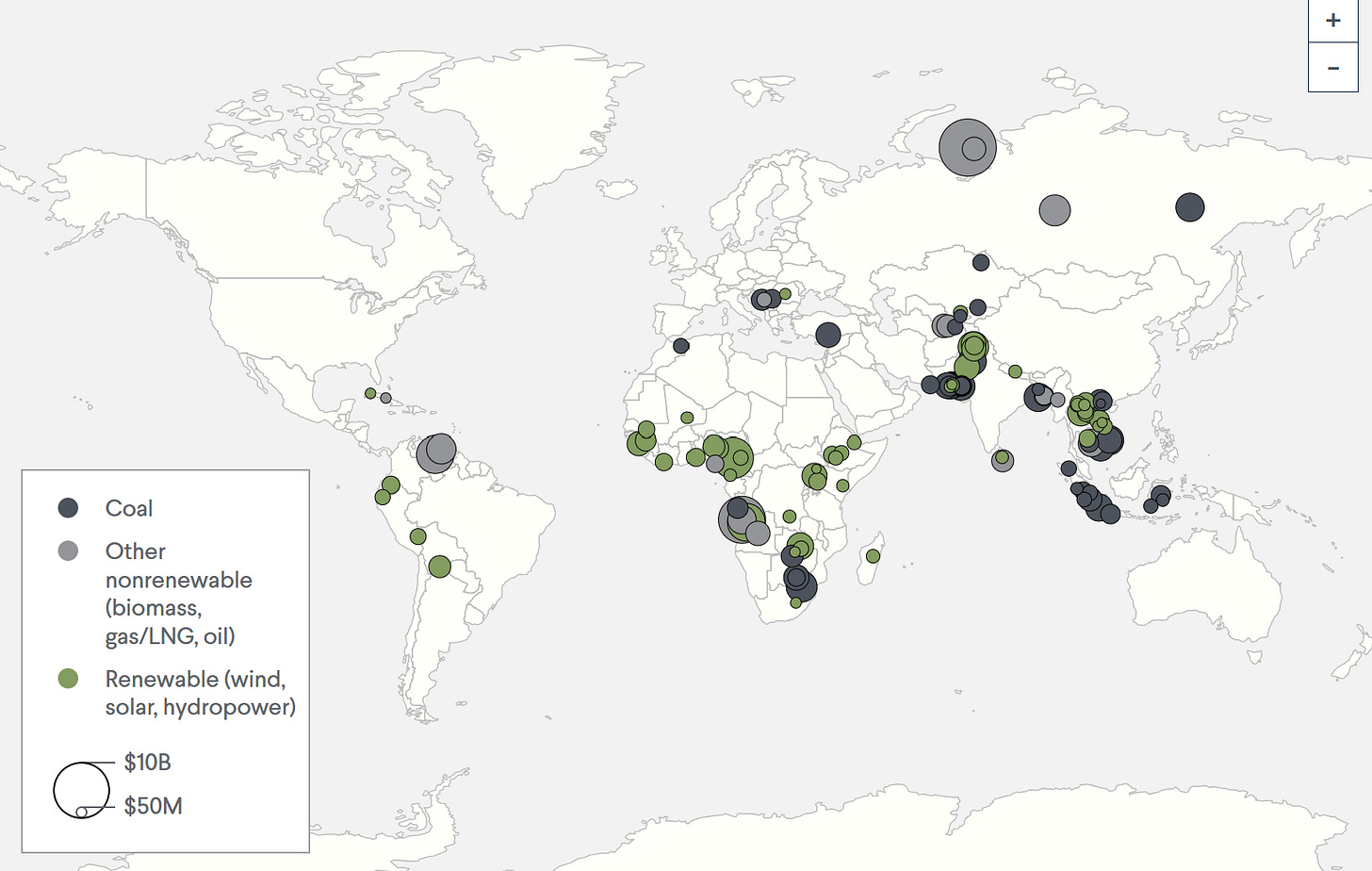

Second, infrastructural requirements for AI diffusion increase with increasing adoption, and become more idiosyncratic. A 2024 advanced economy naturally has about enough energy, grid stability and GPU supply to run enough inference to stay at the adoption frontier. The same can not necessarily be said about that same advanced economy in 2028. Supply of computational resources to diffuse AI through an advanced economy is bottlenecked by major government decisions, e.g. relating to enabling the buildout of necessary power supply or allowing for the large-scale construction of data centers. If a middle power does not very actively prepare today, its participation in future AI progress can be hamstrung severely.

Two Objections

A US reader might be inclined to interject that this all sounds like tough luck for the Europeans, but should not bother the great powers all that much. But paradoxically, the lack of awareness on middle powers’ parts actually makes them worse targets for leveraged exports and diffusion. Negotiations around AI diffusion are fundamentally asymmetrical: The great AI powers do not only have a lot more leverage, they are also more aware of how important striking productive deals is for the middle powers. The leverage helps them, but the awareness gap hurts them. Because middle powers are not aware of how much they need diffusion, they might be unwilling to make the kind of lasting major concessions in return that would make for stable bloc-building in the face of great power competition. Entering diffusion negotiations with many middle powers is a bit like going back in time to 2015 to sell NVIDIA stock - you’ll still find willing customers, but I’m not sure they’ll be pricing in the AI-driven payoff very well. From a US point of view especially, more awareness is almost bound to help you: Any currently feasible plan for a vaguely aligned middle power hinges on importing something from the US. More awareness just makes them want that more.

Will things get bad enough to shock middle powers into turning their ships around — a ‘wake-up call’? I don’t think so: it’s very easy to simply sleepwalk into local economic downturns and global geopolitical volatility. This can take the shape of smoothly accelerating trends: The rest of the G7 will just be outgrown by the US more and more rapidly, fall more and more behind on digital adoption. These trends exist today and still cause little panic – by and large, middle powers are focusing on their idiosyncratic politics of the day instead. Things just get bad very quickly by becoming a little bit worse every day. Like observing a train crash in slow motion, there’s just something misaligned about the initial perspectives, something off about the situation from the start: we just end up with no deal, and way more limited AI proliferation than we might have had. There is no month to month news that cuts deep enough to wake that slumber. And the awareness gap just keeps growing.

What’s Next?

It’s quite hard to see a way out of this; and the diversity of middle powers forbids blanket solutions. But any strategy has to start at creating genuine national awareness and buy-in — the time for clever workarounds seems over. A past strategy of some thoughtful people doing work in middle powers has been to go for cheap wins: improvements of their respective positioning that didn’t cost them much, but mattered a lot for AI futures specifically. The issue of the awareness gap allows for no such clever interventions: it specifically requires salience of AI progress with top-level decisionmakers, and it requires them to be actually willing to enter costly trade-offs in their foreign policy in favour of continued AI access.

This kind of commitment does not come easy or cheap. In that context, it’s important not to overindex on big-ticket announcements by AI middle powers – ‘AI strategy units’ or compasses of different kinds might indicate some prima facie awareness, but not the kind of comparative importance that would be required to actually make middle powers act. A realistic assessment requires knowing middle powers by their deeds, as it were. And the deeds are looking dire still: for every one build-out and build-up announced in most middle powers, great powers at the frontier seem to be planning five. This is a Red Queen’s Race: Run just to remain in the same spot. The fact that middle powers are also doing something is very much not enough.

So how to improve on this? Plenty of answers are country-specific: there need to be politically suitable hooks that work the idiosyncrasies of national governments. Simply importing experts, media reports and industry talk from the US has its limitations. It works well to make policymakers aware that something is going on; but it can’t ensure they’ll act on that information. In fact, the effect can often invert: Many European policymakers report that visits by AI lab CEOs have actually made them more wary of grand AI progress claims, suspecting business interests motivating the ‘hype’. The underlying problem is clear: If you want to convince middle powers that it’s in their interest to buy something, the pitch can’t only come from someone suspected to have a stake in the sale. As a result, policy organisations of all stripes are ill-advised to wait for a default trickle-down of AI awareness to middle powers. Actual local work is necessary.

Still, the US has reason and ability to play a part here, too. Beyond all current unrest, the US remains a trusted ally to many middle powers. It can and should try harder to communicate what it knows about AI to its allies. This is different from US-based stakeholders, whether that’s companies or thinktanks, doing so. If it comes from the most trusted elements within the government – for instance, its established players in foreign and security policy –, US advice might still be heeded. The US should get more serious about spreading this awareness, even as a matter of shallow self-interest. To a limited extent, I will say that the same logic should apply to the UK as well, which seems uniquely aware of the ramifications of AI progress and still well-connected to many other influential middle powers. Letting the awareness gap grow is not in their interest.

But beyond initial ideas for pathways toward solutions, I think a change in perception is most critical. The US policy environment holds most of the cards these days – and I think it’s mistaken to be unconcerned about the dismal state of middle power AI policy. Building and deploying advanced AI systems is a fickle task even under ideal conditions. Trying to do so amidst rising geopolitical volatility seems even harder. From a great power’s driver seat, winning the race must feel amazing. But a racetrack with every other driver asleep at their wheel is perilous terrain.

By which I mean advanced economies with no strong independent standing in AI - for a rough proxy, take perhaps the G20 minus US and China; though the UK is clearly primus inter pares among these countries.