AI & Jobs: Leverage without Labor

Would humans flourish under full automation?

Serious people increasingly voice serious aspirations of AI that will do all human work. That means the issue on the table is ‘full automation’: if AI displaces most human work, will our institutions still enable human survival and flourishing?

The right way to frame this question may be leverage: do humans retain the power to defend favourable arrangements? Look around, and you’ll find optimists telling you yes, in the absence of material scarcity, there’ll be enough to go around and little need for hard leverage; and pessimists telling you no, the need for labor is what staves off the prospect of a permanent underclass. Between these two, I’ll argue for another view: our institutions would handle the immediate aftermath of full automation quite well, but irreversibly deteriorate in the absence of mutual leverage and common manners. To avoid that fate, we ought to close the growing gap between the pace of automation and institutional adaptation.

Compared to many pressing issues in AI policy, this essay considers a problem further down the road. For the foreseeable future, I believe the frontier will remain jagged and comparative advantage will persist – we might well run into many other problems before we ever have to start worrying about full automation. Many thoughtful people realise the same and argue that therefore, this debate is not worth having. But I disagree: leading developers and thinkers consider full automation possible, and are already planning for it. They either outright advocate for full displacement, or aim to relegate human work to a smaller, less important part of the economy, closer to a feel-good channel for welfare payments than a trade of economic value for commensurate wages.1 In an era of surprising technological progress, some of it driven by these very voices, I’m inclined to take them seriously enough to discuss full automation today.

No matter whether full automation is ultimately technically inevitable or not, we can imagine many different paths toward it – paths we choose today. So we ought to ask: do we find the current default story of full automation desirable? To get a better sense of what that story looks like, I suggest we consider three clusters of views.

The Thin Veneer

The first view is what I’ll call the ‘thin veneer’ view of labor and society. It holds that distribution of wealth and power stem from hard leverage. Democratic institutions, welfare systems and charity are but a thin veneer over this system of leverage — they exist because if they did not, humans would protest by withholding economic contributions. They could strike, lay down their work, cease consumption, and so on. Indeed, the view goes, this is often how they arose in the first place – rights were ceded to groups that had the power to take them. This thin veneer view is not only about labor, but also about violence: the implicit threat is not just of strike, but also of violent revolution. But with the rise of increasingly autonomous weapons that change balances of power away from the many toward the few, the economic part of leverage seems more material right now. This first view runs with the implications of that, and fears the changes in leverage dynamics will upset our social contract.

On the ‘thin veneer’ view, good outcomes after full automation seem highly unlikely. Once governments and capital-holders – anyone directly involved in the AI economy – do not need workers anymore, why enable them to have any kind of good life? Perhaps they’ll still pay them a subsistence amount, perhaps not – but they definitely have no incentive to provide for anything that comes with even a marginal cost. The thin veneer view also applies to the softer version of full automation, wherein humans hold on to increasingly irrelevant jobs that make up a smaller and smaller percentage of the overall economy. That’s because that scenario still implies a substantial relative decrease in human workers’ share of the economy, and thereby a necessary comparative decrease in their leverage. To the extent that the thin veneer advocate thinks the current welfare of workers is downstream from their current leverage, they’d also think a decrease in that leverage comes with a commensurate decrease in welfare. Note that this ignores deflationary effects from AI – more on that later.

What does the ‘thin veneer’ view make of the power of humans in their role as consumers, not workers? Surely, the AI economy requires inputs to continue running? Yes, but not necessarily from a breadth of humans – consumption can instead come from a smaller and smaller group of capital owners and stakeholders in the AI economy. Welfare payments likewise don’t confer leverage through consumption: counterfactually, you could just withhold them, not levy the taxes required, and approximately the same amount of consumption happens anyways.2 A similar reason makes it so that ‘universal basic compute’ does not change the equation: if all the owners of distributed compute hold a valuable resource, but no other leverage, can you not just disown them? This is the natural conclusion of the most cynical view – that as the materialist balance of forces changes, so do the prospects of most who get by on work today.

Readers will notice that there’s something distinctly Marxist about this materialist view. Depending on your ideological couleur, that can motivate different conclusions: perhaps you think that AI is merely the obvious endgame to capitalism, the continuation of existing class struggle by different means – and so it requires all the good left-wing responses you’ve been asking for anyways. Or perhaps you think that the thin veneer advocate makes the same claim to inevitability that Marx himself made when he observed the weavers and was quite certain that the revolution was bound to happen any year now. I think you’d be getting at something true either way: that an impending material imbalance might cause serious problems, but that we might just be able to carry on anyways.

The Deep Utopia

The polar opposite view is one of ‘deep utopia’: underneath the current layer of scarcity-driven arrangements, the human interest in mutual welfare and redistribution runs deep – that if we had enough to go around, we’d make sure it went around. Mechanize, a company producing essays and RL environments, prominently espouses this view: in a recent post, they argue that we can and should automate all jobs, and hope humans will survive and flourish on welfare and charity amidst abundant AI-produced goods.

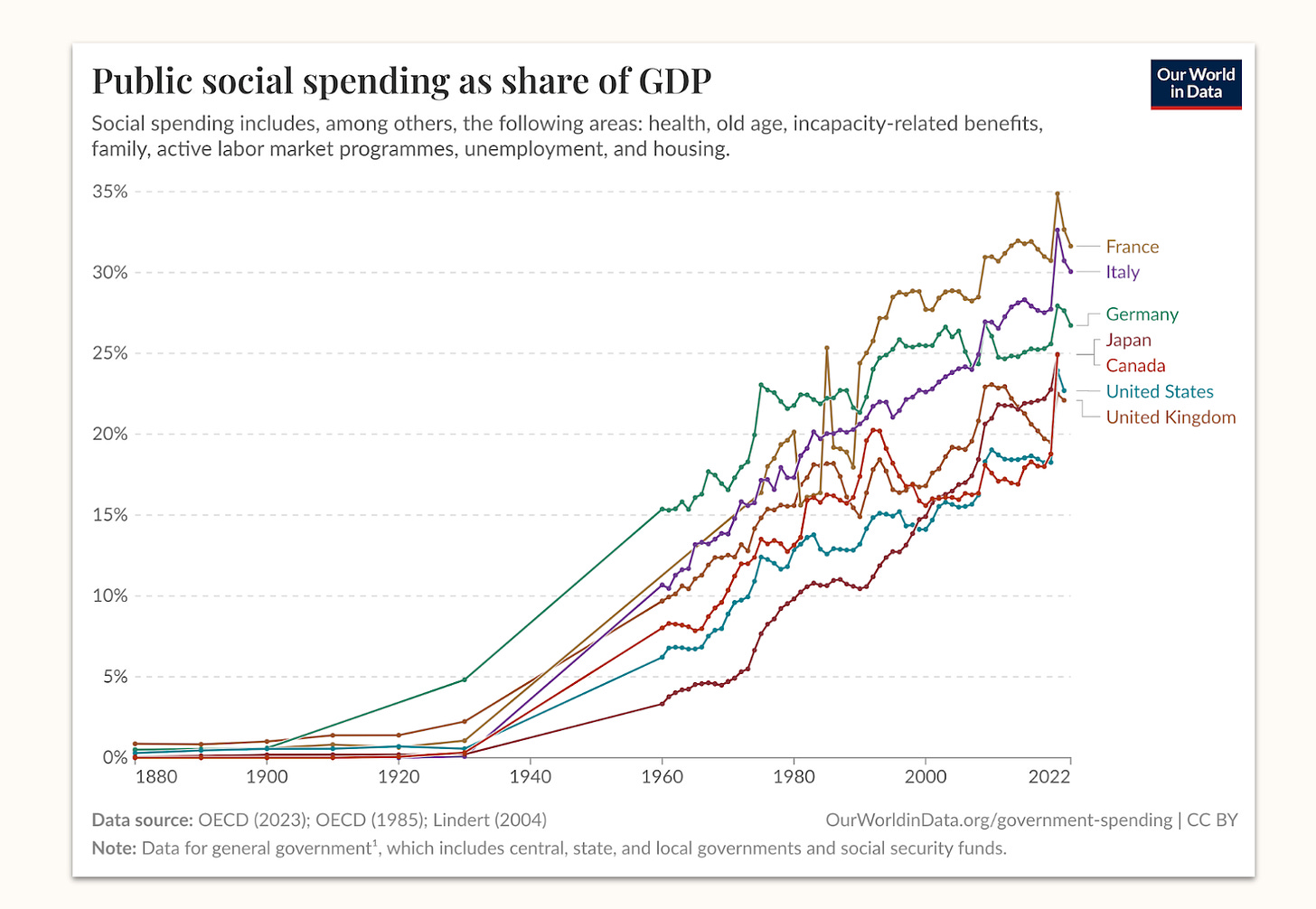

Their argument rests on one sociological and one economic premise. The sociological is to assume a strong trend of increasing charity and welfare continues. This is the point Mechanize make: they correctly identify that as society has progressed over the last centuries, we’ve redistributed and allocated to charity more and more of our resources. If we just continued to do so in the future, as AI-driven growth fills our treasuries, existing channels of redistribution seem set up to deliver material abundance for all. I’m not sure what would be a convincing structural reason for this assumption, and I tend to favour the leverage-forward view for its ability to make some causal sense of that trend. But it is hard to argue with the shape of a steadily increasing graph, and to the utopian view’s credit, the trend has persisted even through what should have been marked shifts in relative leverage, such as the shift of threat of violence toward smaller, technologised militaries. You would need some extraordinary evidence to be sure it would break away as radically as the thin veneer view implies, and I’m not sure this evidence exists.

The utopian view is also helped along by an economic premise, which assumes AI has a deflationary effect on the basket of goods that make up a ‘good life’ today. Because widespread deployment and integration of highly efficient AI systems into supply chains might make it much easier to produce goods and provide services, it would be much, much cheaper to maintain today’s standard of living in the future. As a result, the argument goes, you could sustain everyone’s welfare even by very small payments. I think this claim is right on a very abstract economic level, but it glosses over some important details — increasing material abundance has not always implied a practical drop in the price of one specific lifestyle.

That’s for a couple of reasons: basket of goods change, abundance makes us improve products in ways that also make them more expensive, and Baumol effects make some prices very sticky. Just as much as the life of a 1900s coal miner or medieval peasant would perhaps be cheap to buy today, but you can’t actually buy it, there might not be a way to get by at our current levels of welfare in the future. Beyond that, I’m also quite uncertain whether the most effective marginal deployment of AI systems in a compute-constrained world of full automation would really be creating material abundance for displaced workers, who surely hold fairly little market power as consumers.

All in all, I do think there’s some truth to the utopian view that the thin veneer view ignores: historical trends carry substantial momentum, and it might be easier to feed humanity than you think. But I’m quite doubtful that this effect gets us to the point of ‘paying for a flourishing humanity is a trivial side effect of AI-driven growth’ all on its own.

The Thick Veneer

That brings us to the ‘thick veneer’ view. It holds that our values and institutions run deeper than just economic leverage, but not all the way to the core: once we remove the delicate balance of mutual leverage, our arrangements will eventually slip away. And by the time they do, we won’t have the leverage to get them back – so we should proceed with utmost caution.

This view concedes, first of all, that we might be fine for some time after full automation. From sheer institutional inertia and retained values from the pre-automation time, our institutions might well work to deliver equitable and favourable results to many for quite some time. But that might slip away. Laws, redistribution channels, habits of charities and rules of taxation are themselves highly contingent. The underpinning that would keep these institutions going past the simple inertia of the initial years are shared norms and beliefs – ‘habits of the heart’, perhaps. The inverse means that old institutions can deteriorate as we forget their purpose and lose the norms and circumstances that gave rise to them.

The norms that make redistribution durable rest on social conditions that full automation could eliminate. Today’s redistribution works because most people participate in labor markets, face similar risks, and can imagine themselves in each other’s positions. Even in 2025, there’s still somewhat of a sense of ‘there but for the grace of God go I’ – insurance and welfare still somewhat feel like shared risk pools rather than one-way transfers to a different class. Even those who never need these protections at least share the basic experience of work, the participation in societies that derive pride and purpose from labor, and the ensuing sense of basic desert.

But on the full automation view, only few will be capital holders and live players that still hold substantial leverage over what happens. They are supposed to live lives not only of material abundance, but of importance and purpose, in the knowledge that they’ve escaped the ‘permanent underclass’. They might look onto the rest of humanity with sympathy and compassion, but surely not with the same amount of respect and kinship they felt while lines between classes were still more obviously blurry. How long before the few start wondering why exactly they should continue the trend of charity and redistribution? Before they find something better they’d like to do with the money, some political wedge that has them take offense at the spending of the many, some frustration at whom they might see as freeloaders and how unproductively they spend their time? If our society changes like that, it’s very easy to forget the reasons for why we have set up our carefully calibrated social institutions to begin with.

The deflationary argument implies this won’t happen, because the amounts are so small and marginal. I wouldn’t bet on it, even if I believed the deflation case: recent history suggests even small amounts of very helpful spending might actually be highly susceptible to outright cuts once they lose the leverage to back them up. For just one example, the richest country in the history of the world has cut its global aid payments from a similar impulse: no matter where you come down on the cuts to USAID, they’re squarely evidence that the instinct of ‘why should we bankroll this’ does not stop at small sums or large reported positive effects.

And the insidious part is: if we do get to that point, it’ll be hard to turn back. Maybe current institutions are not only the product of mutual leverage, but we’d surely require leverage to rebuild them and to enforce the costs that this would imply. Today, functioning democracies have a backstop: whenever our manners slip, whenever our arrangements deteriorate and lead down a markedly less equitable path, the people can still change our path. Without remaining leverage, how could those on the losing end of a new arrangement ever make their voices heard? Meaningful democratic enfranchisement, with a government that can and will actually make substantial changes in response to votes, might deteriorate in much the same way. How would we keep it honest? It sure won’t be strikes or boycotts – that, the thin veneer view clearly demonstrates. And if the few no longer think the many contribute to society, I’m not sure they’ll remain very sympathetic to uprisings and protests. The backstops that would bail us out if we lost our ways still seem based on leverage.

A likely outcome seems to be slow deterioration: cutbacks on welfare and charity, communicated with the attitude of ‘you better take what you can get and be grateful for it’, and paired with a manifest lack of leverage to change that arrangement back. Does that mean full automation ends in disaster, full stop? No. But it means that I’m skeptical that current institutions are enough, or that past trends persist, to guarantee outright flourishing. Tocqueville gives us a good notion of the manners that make this veneer thick, but vulnerable nonetheless:

I am convinced that the most advantageous situation and the best possible laws cannot maintain a constitution in spite of the manners of a country; whilst the latter may turn the most unfavourable positions and the worst laws to some advantage. — Alexis de Tocqueville

Implications

I favour the ‘thick veneer’ view, in the sense that I think it’s what would happen if we implemented full automation today without changing our societal arrangement at all. I find the plain cynical reading of human nature as unconvincing as the bright-eyed one, just as much as I find the reductive materialist view as unconvincing as the naive extrapolation of societal trends. Society is far less of a ruthless optimiser one way or the other than you might give it credit for from San Francisco. Even if a radical technological change – like massive progress toward full automation – manifested from one day to the other, society would move quite slow in updating our arrangements to reflect that fact. We’d be as slow to weed out the sudden inefficiencies as we’d be to plug the sudden holes in our welfare state, and I assume that much of society would slowly grind along for quite some time. But the underlying shifts in mutual leverage and shared manners ultimately, slowly rise to the top, and things go wrong – a whimper, not a bang.

This prospect of delayed deterioration implies a need for risk aversion: even a tentative believer in the deep utopia would be well-advised to act in accordance with the thick veneer view. If the adverse effects of full automation come slowly, pervasively and insidiously, we have very little live signals to react to – especially if full automation moved at a hastened speed, and societal reaction did not. By the time we found real-world evidence that the utopian view did not work out, it might already be too late to fix the underlying societal structures that we had hastily changed.

What to make of this?

I don’t think the ‘thick veneer’ future is a necessary conclusion of full automation: even if we couldn’t choose to avert full automation in the face of economic pressures, surely we can nudge its trajectory. If our institutions keep up, we could prepare them to get this – unlikely – scenario of full automation right. Today, I think our best course of action comes down to a dual strategy: we need to make sure the pace toward full automation does not exceed the pace of expanding institutional capacity to handle it.

First, we should scrutinise, and sometimes hinder, plans to accelerate toward full automation. There is a speed that is manifestly too fast – one that most people in the world have a justified grievance with because it would strip them of their leverage without giving them enough in return. I think if you gave them the outline and odds of the deal the utopians offer, they wouldn’t want to take it. They might be right, but even if they weren’t, they should get a say. To add, there is a pace of automation that exceeds all ability of institutional adaptation. Before we reach it, we should rather slow down. We can do so intelligently and elegantly, by carving out incentives for human roles to remain vital along the slower parts of the jagged frontier, by requiring humans in the loop only where they add to that loop, and by boosting and supporting augmentation far enough that automation does not outcompete augmented workers. If we don’t, public discontent could manifest in much less elegant policy that adds frictions where we’d want lubricants and prohibits the use of AI systems where they’d do a lot of good – if you think requiring drivers in Waymos were bad, just wait a couple of years. We should rather find a better way to regulate our pace in accordance with the will of the affected.

Second, we should think toward institutional capacity for a post-work future. The thin veneer view explains to us all the ways in which our current institutions are insufficient: they do not confer durable ownership absent leverage, they lack any mechanism for an international component to charity and redistribution, and they often fundamentally operate on the premise that being out of economically valuable work is a temporary phenomenon before or after a stint in the labor market. That premise needs reexamination, and many of the issues need addressing. There are many ways to conceivably do this, and way too few people are working on this. As to what I think, I’ve written about all this in much greater detail before and will spare you the repetition – the gist is: a good solution would need to be somewhat global, somewhat durable, and try to retain most humans’ ability to make valuable contributions. We’re nowhere near a proposal that gets any of that right.

Between these two options, I think we should avoid slowing down AI progress whenever we can. First, because I believe AI systems promise tremendous welfare, wealth and growth, and I think we should build their most advanced versions sooner than later, all else being equal. But second, it’s for a political reason: fighting full automation by aiming at preventative prohibition doesn’t seem viable. Any attempt to halt AI research in total is going to face a very difficult political economy – both as it relates to the domestic loss of autonomy and productivity, and as it relates to foreign competition. The same goes for attempts to steer away the technical paradigm from full automation toward narrow capabilities and augmentation, insofar as the former are much more efficient. Slowing full automation through negative advocacy is a costly zero-sum game; hastening institutional capacity or developing actually competitive alternatives faces a far better political economy.

But we can’t build our way out of every conundrum. In particular, accelerationists should be mindful that politics enforce a natural speed limit here. If you go too much faster than the institutions and the public, they will backlash and violently halt your project – and leave you with little to show for in terms of ‘hastening inevitable technological marvels’. As fun as it reads on X – it’s not actually a great omen if your company makes it to the top of a Bernie Sanders report before its first product.

That means accelerationists in particular should get on board with improving the institutional setups we need to navigate the post-automation world well. They used to be better at this, but I’ve recently been disappointed to see that they seem to be giving up on this mission – whether it’s Sam Altman moving away from redistributionary messaging like his UBI experiments, or whether it’s the Mechanize crew posting essays on why everything will turn out great anyways. How fast you can scale your dream of full automation depends on how fast we all manage to scale our path toward institutions that can handle it. An accelerationist, in their naked self-interest, should help to do that more.

This is a tremendously complicated issue, and I still believe that our technological trajectory does not, in fact, point at full automation. But if it does, you should recognize we’re headed for a discontinuous shock to the incentive structures that underpin the setup of modern societies. Even the most confident extrapolation of history does not reliably make it across this event horizon – no matter whether your reading of choice is of the utopian or dystopian flavour. So if this is the path we’re on, we should walk it at a pace that makes it possible to still consider where we step.

Note that such roles would be different from sticky ‘human preference’ jobs that would be a genuine high-leverage bottleneck for the post-AI economy. Jobs arising from comparative advantage would sit somewhere in between, depending on how costly it would be to replace them with AI work.

Correcting, I guess, for different flowthrough speeds of money – but surely, that’s easier addressed through interest rates and taxes than through doling out money to consumers.