AI & Jobs: Politics without Policy

Political support mounts - for a policy platform that does not yet exist.

A political window is opening up: policymakers are waking up to AI-driven job market disruption. A critical mass of headlines, studies and well-placed arguments seems to have gotten the attention of mainstream political players – culminating in a strange confluence as both Barack Obama and Steve Bannon have predicted that AI jobs loss will be a major political topic soon. For the purpose of this post, I’ll go with their assumption, too — and examine what the resulting political constellation means for the next months of AI policy.

Policy debate will follow on the heels of current political momentum. Policymakers will want to get their names on bills, provide solutions early and claim political ownership of addressing a rising concern in the name of their party. Policy organisations on frontier AI, from developers to safety advocates, will be invited to play their role. In itself, that makes for a promising moment. Job disruption is one of the few impacts of advanced AI that are already legible from the point of view of today’s political mainstream, and therefore one of the few starting points to make impactful AI policy today.

But the debate could quickly go off the rails: existing policy ideas to address AI-driven labor disruption fall short: they either fail on technical merit or on political viability. If policy experts can’t provide strong ideas, proposals will come from political operatives instead, and move the debate away from the expertise. The ensuing debate could see today’s frontier AI policy ecosystem — policy-makers, developers and policy organisations alike — relegated to the sidelines and consigned to political irrelevance.

Political Momentum Is Building

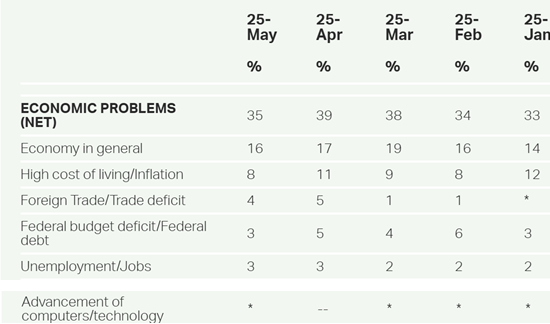

AI job disruption makes for an excellent political hook because the stakes are both clearly high and very well-established. High, because losing jobs is impactful and politically salient: Individually because no one likes to lose their jobs, and collectively because the blame for widespread job loss is usually placed on policymakers. And well-established because the general pattern of ‘jobs get lost because they are automated’ is well-understood from previous waves of automation and globalisation. Yes, these previous waves have ultimately been net positives; but that is not how they tend to be remembered politically, with localised displacements like in Appalachia, the Rust Belt, in former coal-mining regions etc. leaving long-lasting political scars. Many other risks in AI policy do not share this favourable political framing: either their stakes are too abstract, like in the case of harms to intellectual property or privacy, or their high stakes are not well-precedented, like in the case of loss of control or gradual disempowerment. Labor disruption is uniquely suitable to facilitate AI policy’s break into mainstream politics.

In practice, I think this leads to three effects. First, it makes political strategists think they have their hands on a ‘wedge issue’ – a political question that can favourably split the electorate with a majority on their side. Both Democrats and Republicans might think AI job disruption plays out in their favour. Democrats think so because AI job displacement plays nicely as a response to the GOP alignment with Silicon Valley ‘oligarchs’, who have low favorability ratings and can be linked to the disruption. Republicans think so because AI job displacement plays well with the overall economic populist platform that puts a great emphasis on retaining jobs and economic perspectives in a fight against global and technological trends. Both might hence rush to put their spin on AI job disruption to drive the wedge just right.

Second, opportunistic policymakers may think they have a chance to jump on an emerging issue early. Linking issues to platforms is a politically savvy move: Usually, conservative parties benefit when ‘migration’ is an important topic, and left-wing parties benefit when ‘inequality’ is an important topic. If you think ‘AI’ is going to be an important topic, you want your party to be the ones who benefit from its rise, so you want to get onto the issue early. There are related individual incentives: If you are the person in your party who gets on the AI train early, it might take you to prominent positions on account of your perceived expertise. And third, thoughtful policy makers think they have their hands on an issue in genuine need of thoughtful policy that needs addressing. I’ll let readers evaluate which incentives respectively might drive the many recent statements on AI-driven job loss.

As a result, there’s vague political support in the air for any policy idea that fits the following bill: It conceivably addresses some section of the AI job loss worry – e.g. by eliminating or slowing the displacement threat or by providing for alternative avenues to material sustenance or to genuine meaning; and it interfaces well with the politics of its would-be partisan champions. If such proposals came around, I think they would have a decent shot at entrenchment in any party’s platform and political rhetoric, and might well have sticking power through to 2028 and beyond. Without good proposals, two things can generally happen. First, politicians might lose enduring interest because after all, there's nothing concrete to do to ground rhetoric. Second, we might get inadequate solutions that sound good but don't work. I believe we’re headed for the latter by default: the political energy is too high to dissipate, but lacks viable policy solutions to gather around.

Current Options Are Lacking

It remains a bit unclear what exactly all the labor market concerns mean in terms of policy. For a political concern to stick around and develop real impacts, it needs to be readily relatable to concrete policy proposals. Currently, no politically viable policy proposals on AI job disruption exist. Instead, past work on this is either positioned on the political fringe or lacks the kind of instant actionability that makes for a satisfying political move. The yardstick to evaluate these proposals is: if you are a mainstream policymaker, would you feel good about introducing them as a draft bill tomorrow? Current ideas fall short. Let’s look at some:

Universal Basic Income

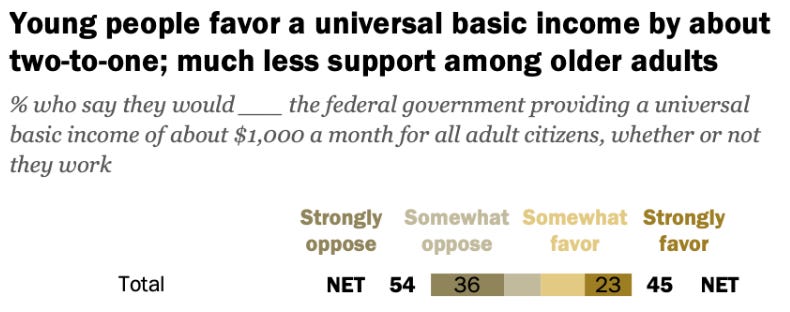

Universal Basic Income (UBI) was long thought to be a sort of gold standard of post-AGI economic structuring, and so it was readily pasted onto the current permutation of discourse on AI and the labor market. But UBI has practical problems, in that it does little to alleviate two central problems of AI job disruption: lack of meaning and lack of standing. The former argument is clear;1 the latter goes as follows: Simply providing transfer payments to people answers the acute question of their solvency and sustenance, but it does little to alleviate their disempowerment. One issue with widespread job disruption is that without their usefulness to the labor market, people at large have much less political leverage compared to leaders and corporations.

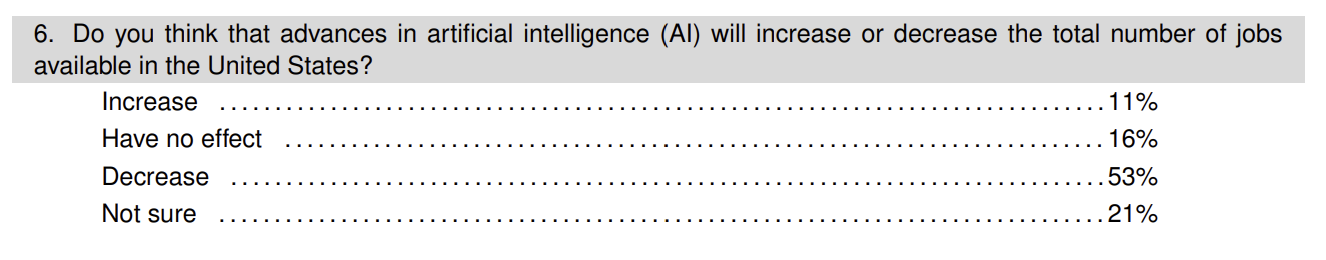

Giving them some money changes this a little bit because it maintains their status as consumers who exert power by ‘voting with their wallets’, but not by a lot – fundamentally, a government could just stop paying them their UBI at some point after they have lost their leverage. But perhaps the bigger problem is that UBI is just not all that politically popular. In 2020, a majority of Americans already opposed it in principle. I think that’s bound to get much, much worse once the usual rhetoric around investing tax money into blanket social services picks up: Usually, transfer payments sound good in principle when people think of themselves as recipients, but play worse and worse once political opposition suggests they would be net payers instead. I think a somewhat similar issue extends to otherwise promising measures, like ‘predistribution’ or codifying windfall clauses: they brush against an administration and political climate very far away from outright redistributionary intervention.

Compute Provisions

Universal Basic Compute (UBC) is a newer spin on basic provisions, advanced prominently by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman after disappointing empirical and political results of his previous UBI advocacy. UBC solves some of the problems with UBI: compute might be something like productive capital, and an enduring compute share that you can leverage to maintain relevance seems like a more durable solution. Or you can just sell it, and then it’s basically UBI. There is plenty of technical debate to be had on this that goes beyond this post, but it definitely faces political shortcomings, mainly: No sizable constituency in the world currently thinks ‘compute’ is something particularly useful to them, so the prospect of receiving UBC instead of a job will not play well as a political platform right now. Even if you frame UBC as ‘basic access to powerful AI’, it might not play very well: It takes a lot of imagination to conceive of the world in which that is enough, i.e. one in which prices of basic goods collapse and powerful AI can easily be wielded to achieve marginal profits. With UBI, at least you’re giving people money, which they know they want.

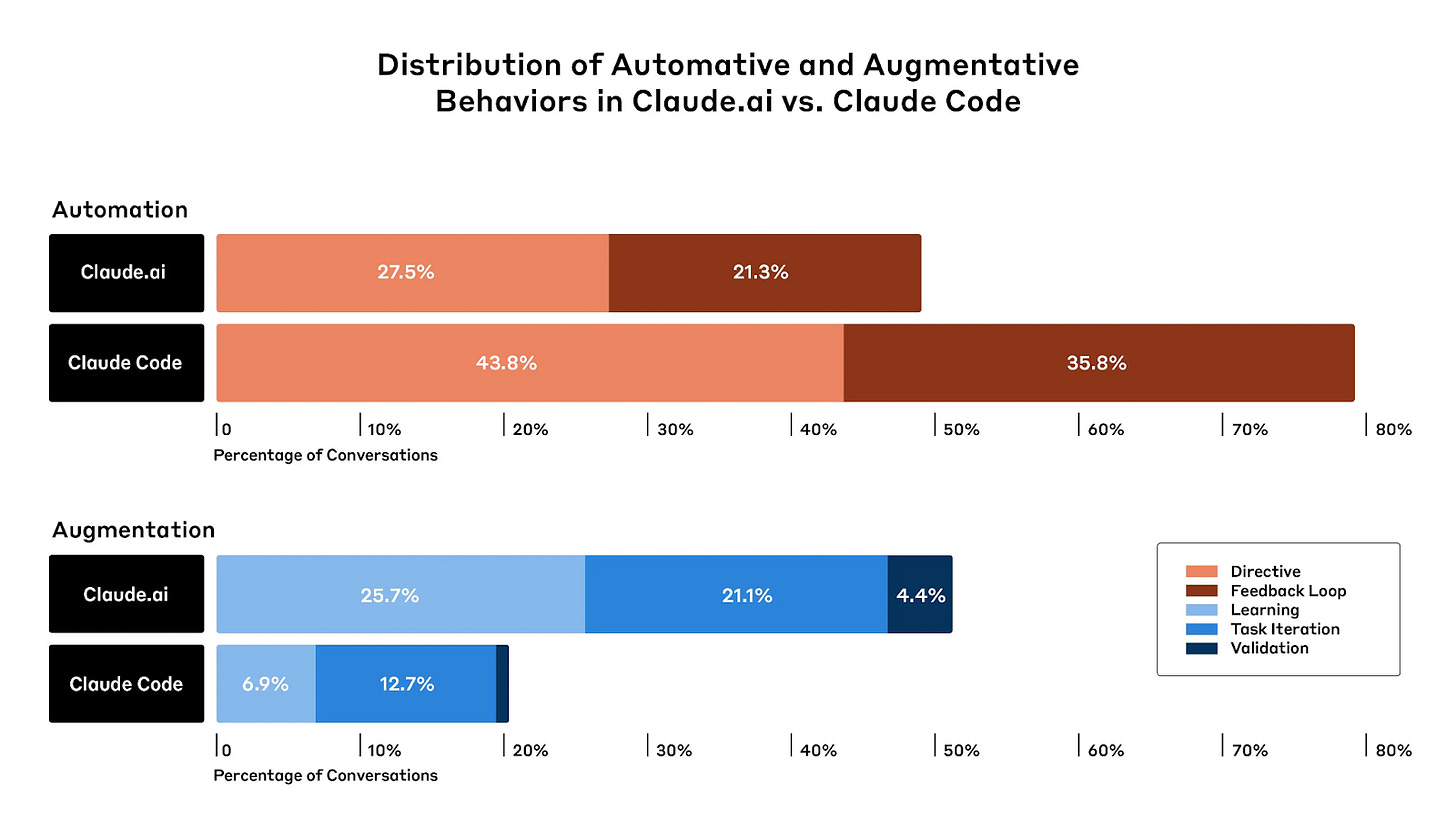

Human Augmentation

Human augmentation is a rising cluster of alternatives aimed at deploying AI systems to augment humans instead of replacing them. Weak versions of these proposals endorse legal stipulations to forcibly keep ‘humans in the loop’ of important decisions — thereby indirectly relegating AI systems to augment these looped-in humans. These framings are politically fraught: Both the intranational economic and international strategic landscape of competition are charged with incentives against the slowing effects this could have. And requiring human sign-off sits rhetorically close to bureaucratic hurdles and unnecessary procedures which currently already face strong political opposition.

A stronger notion of human augmentation is provided in the ‘Intelligence Curse’ essays, which convincingly describe the dramatic effects of an AI-agent-driven paradigm for our current ‘social contract’. But while I think the analysis is accurate, I’m less excited about the included political action guidance. True, in the outgoing chatbot paradigm of AI systems, augmentation is an exciting prospect. But technical progress is going down a very different path. Paradigms are very centralised and highly focused on developing more and more agentic systems. Coherency over long time horizons, system design for independent execution of complex tasks etc. are all (a) economically incentivised because they provide the most solid moat to model developers and (b) seem most technically tractable – and so that’s what’s being built.

It’s very difficult to steer the course of technological progress away from these attractors. In trying, any policy platform would risk burdening its own economy with subpar AI systems at best and hamstringing its AI ecosystem at worst. Supporting augmentation technology and a shift toward different paradigms through research and incentives seems prudent (and I’m very excited about the prospect); but the overall vision might not have the technical maturity to make it a sufficient policy platform for this current window.

Adoption Barriers

Adoption barriers to AI seem like an obvious short-term fix, especially if you think that AI isn’t going to be particularly useful. One of the reasons why people think that legal professions might not be impacted by AI immediately is because it would be illegal for AI to carry out certain tasks. One could willfully expand this principle and ban AI from being deployed in plenty of other ways. In due time, firms would find workarounds, but there would surely be a slowing effect, if only through enormous intermediary regulatory uncertainty. Erecting these barriers could play well with some groups – unions and intensely anti-technology crowds in industry come to mind. But these are not the key players in this debate: their jobs are less likely to be affected, and they currently do not hold their respective parties main favour. On the other hand, both parties have good reason to steer away from plain adoption barriers: Republicans to keep the allegiance of their new tech right allies, Democrats to avoid playing into the stereotype as decelerating technophobes. No matter what side this coin lands on, adoption barriers are clearly not a meaningful solution: automation pressures from global and local competition will continue to increase. At sufficient scale, irrationally restricted economies will get outcompeted and left behind.

All this means: The policy solutions with which the broader frontier AI ecosystem has come up so far are not suitable for political consumption. So while AI developers and AI policy organisations might initially be the first ports of call for policymakers that want to get into the AI job disruption debate, they might not stick around: Their ideas might not seem workable or effective enough, and so they won’t be the primary advisors or expert testimonials, and they won’t be sponsoring any bills. This is not only a problem for civil society or ‘AI safety’ organisations. AI developers specifically are strongly incentivised to stay very close to this debate: they want to be the ones who provide the solutions, because the alternative is dire. If all the latent political energy in favour of ‘doing something’ about AI job disruption is not steered by experts through somewhat suitable policy, it might discharge more spontaneously. That’s rarely good news.

Room for Nonsense

Where there’s latent political support in the air, actionism usually follows. In the absence of thoughtful policy proposals, that usually can mean more attention for less well-developed ideas. These ideas are usually simple copies or adjustments of existing policy platforms roughly adapted to the current situation without much further thought.

Just for some cursory examples: Union-aligned pro-labor policymakers on both sides of the aisle could endorse anti-automation stipulations like the ones on US port automation; antitrust advocates could endorse breaking up associations between AI developers and the largest tech companies; reindustrialisation-focused tariff advocates could double down on their platform to create AI-resistant jobs; and so on. All these proposals don’t really get to the heart of the matter, and hold very little promise to fully address the problem. They serve the political purposes listed above – but only if they’re uncontested by thoughtful policy ideas. I have enough faith in democratic electorates to think that cheap opportunistic reframings will be outcompeted by genuine solutions in the public debate. But when there are no genuine solutions in sight, cheap reframings might take over the discussion.

At first, that’s only a policy problem: The political window to address AI job disruption is not used well, and so AI job disruption hits unnecessarily hard once it rolls around, and we could have done better. But it quickly becomes a problem for the broader political dynamic. If policy organisations with the greatest expertise – like today’s frontier AI policy orgs or AI developers – can’t provide politically effective solutions, they risk being shut out of the policy process. They might still get considered insofar as they can exert political leverage, but they lose access on their ticket as trusted advisors. Then, the important policy discussions shift more and more toward the political and away from policy expertise, all the way until an expertise-driven policy environment has shifted into an incentive-driven political environment. The way to stop this is to shape the terrain early: once political windows open for policy on AI-related issues, those ‘in the know’ have to provide politically acceptable ideas to policymakers. The time for that is now.

Outlook

At this point, I find myself in a familiar situation: I have grievances with the current landscape of policy proposals, but can’t offer a silver bullet alternative. In lieu of a magical solution, I at least want to point at some incremental-but-promising spins on current proposals that I think might perform well at the current time.

The first are bundled solutions: On their own, most of today’s proposed measures don’t cut it politically. But in combinations, they might become a little bit more appealing. For instance, you could suggest legislation that combines adoption barriers with incentives to human augmentation; framing the barriers as ‘buying time’ for optimising the technical paradigm toward human flourishing. Or you could link universal compute and income provisions, e.g. by making them complementary or at least as alternatives to individually choose between.

The second is proactive identification of sectors that can absorb displaced workers: Eventually, advanced AI might eat most human employment. But surely, the displacement frontier is as jagged as any other; and some jobs will hold out much longer than others. Identifying and supporting industries with likely low displacement early serves a double purpose: It bolsters industries that can absorb short-term displacements, and it creates strategically important capacity at bottlenecks for advanced AI. This has the benefit of a pleasant political economy for two reasons: First because of historical precedent, where successful automation waves have been absorbed by economic growth elsewhere, as VP Vance likes to mention; and second because it fits the general thrust toward rebuilding capacity and jobs in manufacturing that shapes the current administration’s economic agenda.

The third is developing minimum viable policy for augmentation-focused AI deployments fast. This is admittedly a bit more of a moonshot, but I think there’s merit to exploring it today. The most urgent threat to the stabilising effects of Jevons’ paradox, comparative advantage and absorption by other sectors comes from cheap autonomous, long-horizon agents. And if the economic deployment of advanced AI systems further locks in on the path of autonomous agents, augmentation-focused proposals will have even less leverage. The more central agent-based systems become to economic and perhaps strategic use cases, the harder it will be to steer away. So perhaps the current window is the last instance where fundamental course corrections along that dimension are really in the cards. There are potential efficiency losses from keeping human bottlenecks around, and there are good prima facie reasons to believe that long-horizon agents have economically meaningful efficiency and coordination benefits over augmentation-focused paradigms. But I think the political economy of proliferating AI benefits and of safeguarding against risks is so much better under an alternative paradigm that action now might still be prudent.

I think combinations of the above can make for good policy pitches. A more restrictive, barrier-driven version that still prominently includes grappling with a high-automation endgame might be pitched to organised labor and its representatives; a more hands-off version that presents concessions as backlash prevention can be pitched to more pro-disruption players. These inevitably vary from party to party and faction to faction — and so there is work to be done both in developing more sophisticated policy and in tailoring it to the political requirements of the upcoming fight. The important part is: A promising policy platform has to tell a story that seems satisfying to today’s voters, while still providing some adequate perspective on tomorrow’s likely level of disruption. I think the above might check some of these boxes.

A real window of political support for action on advanced AI and its labor impacts is opening up. It’s mainstream enough to have real influence; but it’s also mainstream enough to be legible outside of the frontier AI policy environment. That raises a challenge: To align the nascent window with the space of reasonable ideas, frontier AI policy advocates need to move fast to capitalise. But ‘the space of reasonable ideas’ on AI job disruption is as-of-yet ill defined. There are few viable proposals, and even fewer still with a good fit with any party’s political DNA. In principle, the players at the current frontier of AI policy - labs as well as policy organisations - are well positioned to make a major contribution here. But if they don’t, they’ll get crowded out by better partisan fits, and risk being relegated to the sidelines of the biggest AI policy debate to date. This is crunch time for AI labor policy.

Though there are of course optimistic readings suggesting people will spend more time on arts, crafts and start-ups. I think this is true of the people who provide such readings, but it’s empirically unlikely to generalise to the broader population