Mercantilist AI Policy

Reconstructing the doctrine behind US AI foreign policy

Some housekeeping: I’ve joined the Carnegie Endowment as a Visiting Scholar with the Technology & International Affairs team. That allows me to take my writing on this publication full-time: I’ll get to write weekly, and with more thorough research behind it. Your readership is what made this jump possible – thank you so very much.

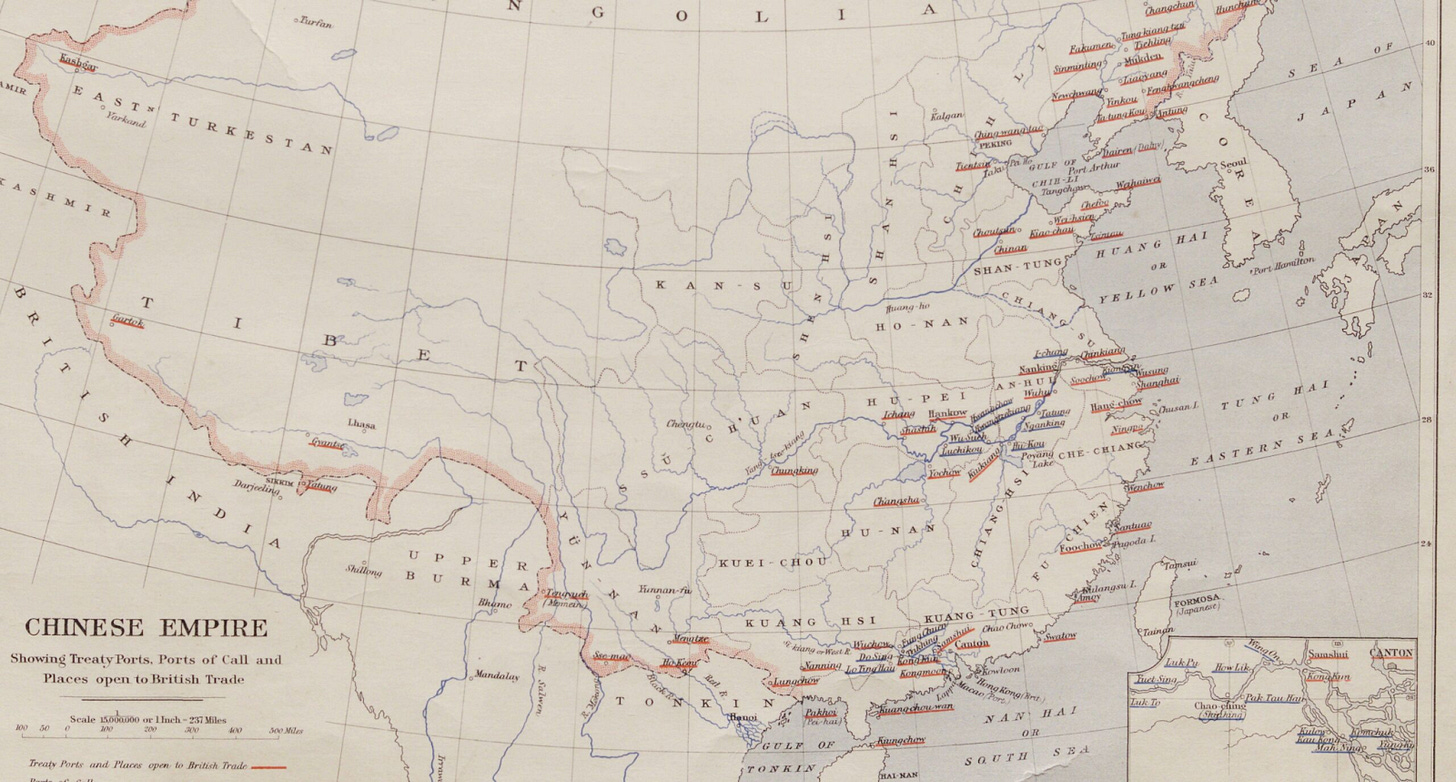

The 17th century was the heyday of mercantilism: Great powers sought to control, sell and export key resources on their own terms to amass wealth and influence. They jealously guarded profitable monopolies at home and abroad, and erected chartered company forts in faraway lands. Today, again, the world’s great power is selling full stacks of coveted technological treasure – on its own terms, through its own chartered datacenters, to any willing buyer.

The Trump administration has lately made a series of controversial decisions in AI foreign policy: Rescinded the diffusion framework, signed an export deal of GPUs to the UAE, permitted H20 sales to China, arguably pressed OpenAI to release an open source model, and laid out an export policy platform AI Action Plan. These decisions have frequently attracted confusion and derision from highly qualified observers. As a result, many AI policy analysts have suggested that there either is no principle behind this foreign policy at all; or that its only guiding principle is myopic cronyism and profit maximisation. I think some criticism of specific policy is well-taken, but on the whole, reductive views of admin strategy risk missing the point. They also gloss over some real - perhaps unintended - benefits for the world.

I think what’s going on here is that most of the administration’s decisions follow mercantilist logic. Mercantilism, of course, is the 17th century economic doctrine that national power comes from maximizing exports, controlling key resources, and maintaining favorable trade balances - often introduced and enforced through monopolising markets, subsidising production, entrenching chartered forts and leveraging trade relationships. Following that blueprint, the US is making a play for full-stack market dominance in intelligence – and is ready to pay a strategic price. Critics of the administration’s AI foreign policy would do well to engage with the mercantilist doctrine, both as a matter of predicting and of swaying the administration’s policies. And the rest of the world should prepare for abundant intelligence, on sale for anyone who can pay.

US AI Policy as Mercantilist Doctrine

Mercantilism 101

Mercantilist undercurrents are not limited to the admin’s AI policy – in general terms, the Trump administration is more sympathetic to mercantilism than most major powers of the last century. It’s much more skeptical of free trade, much more keen on positive trade balances, and much more interested in controlling central manufacturing flows than its predecessors and almost-peers. Also, of course, the administration is decidedly not monolithic - in fact, continued conflicts are raging on a lot of issues in AI foreign policy specifically. But for now, those who subscribe to the mercantilist view seem to be getting their way, and so they’ll be the focus of this analysis. Relatedly, this is not an essay on the merits of mercantilism. If you reject the underlying principles, I’m sure you’ll also reject their applications to AI policy. So, I’m not saying the administration’s policies are good because mercantilism is a good strategy — just that understanding them as mercantilist helps make sense of them.

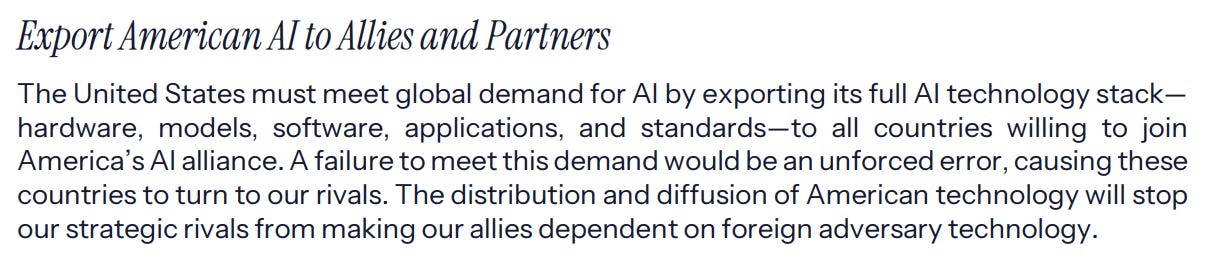

The first and most immediate application of this doctrine to AI was rescinding the Biden administration’s diffusion framework. Rescinding the framework meant abandoning overall upper limits on compute exports as well as highly restrictive thresholds on less trustworthy export nations – closing the door on an understanding of AI exports as something distributed throughout alliance akin to military goods, and opening the door to an overtly mercantilist approach. What comes in its place? It’s not quite clear yet, and the two nexuses of AI trade policy – the Commerce department and AI advisors in the White House – seem to have different reads. I suspect the lack of a comprehensive framework is at least part of the reason why the administration’s policy can seem doctrinally inconsistent from the outside. But between the recent keystone export deal to the UAE and the foreign policy envisioned in the AI Action Plan, we can identify some trends.

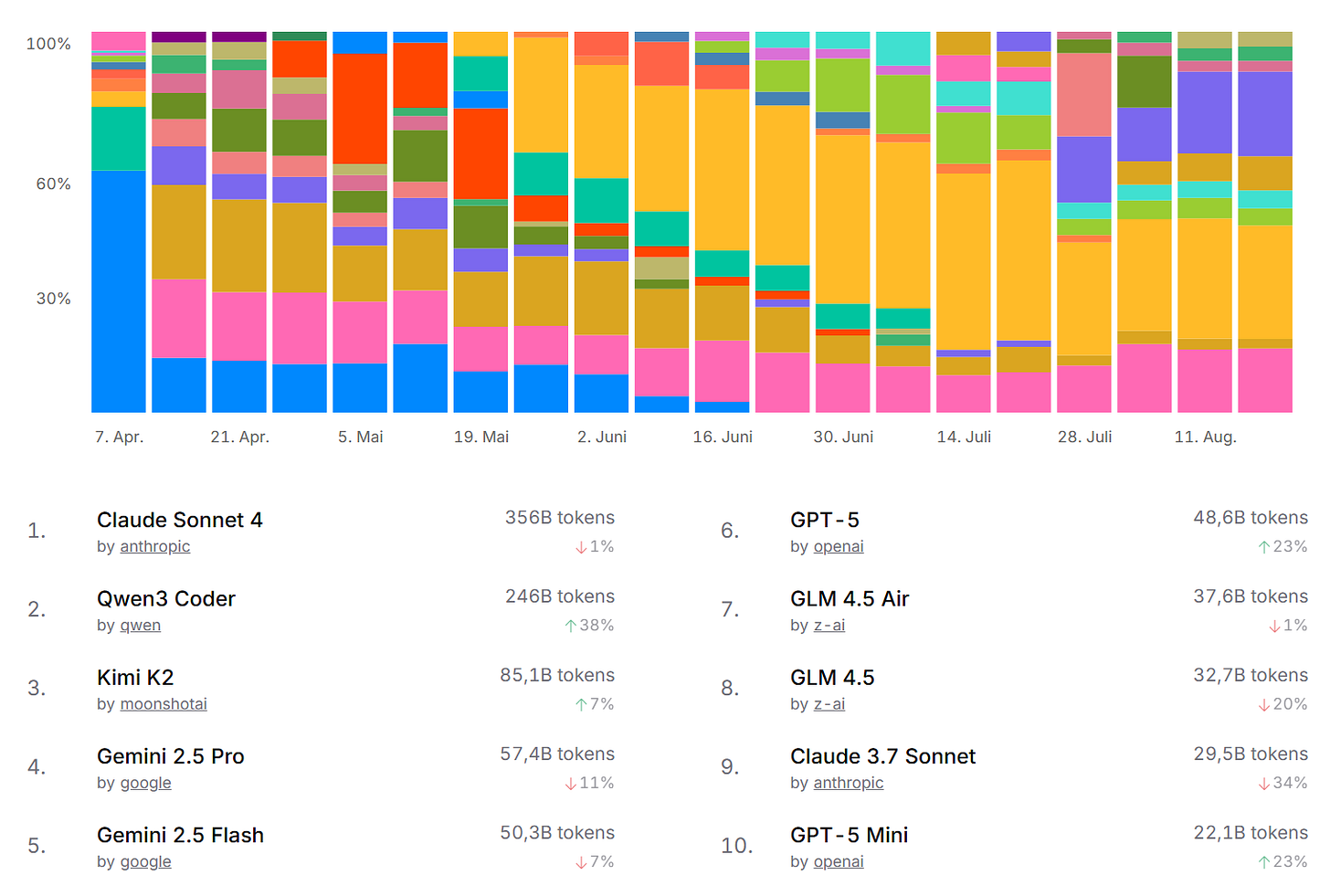

First and fundamentally, the administration aggressively aims at global market share. I think this has a dual purpose beyond the simple mercantilist upshot of selling things at a good price. First it’s culturally motivated: If your AI models populate the world, it is your companies and thereby your domestic oversight that affect a lot of global information flow. If you’re so inclined, you can nudge what the world knows, thinks and believes through domestic regulation – or at least prevent your adversaries from doing the same. But second, it’s about securing market share to capitalise on later: If US AI exports were difficult to attain and expensive, the competing Chinese exports – especially open-source models – would eat into US market share now. That would be an export issue now, and also make it more attractive to buyers to upgrade to more advanced Chinese systems in the future rather than make the swap to the US stack.

Through this approach, the US creates an enduring market for its products by setting buyers up for path dependencies, where they’d want to continue to use similar (US-built) models in the future, and never get roped into the Chinese export ecosystem. In that sense, it also serves as an antidote to any BRI-style inroads that sub-par Chinese exports might make in lower-income countries.

This is, again, a squarely mercantilist perspective: Through leverage over buyers, sellers and prices, mercantilist empires repeatedly ensured near-monopolistic positions for the exports of their own goods. The threat to this position is even greater in low-overhead exporting goods like AI, and so a would-be mercantilist empire needs to support exports even more aggressively.

Chartered Forts, Treaty Ports & Full Stack Exports

Second, the administration favours exporting full stacks – not only models or GPUs or datacenter infrastructure, but an entire package: a datacenter run by US companies, hosting US-built GPUs that run US-trained models. Thereby the US retains control over the avenues of export: As an importer, you can’t just repurpose your imported GPUs to run other models, or run your imported models on clandestine hardware. You can’t even repurpose your nominally flexible chips from training to inference or vice versa without interfering with the property rights of the US provider that runs them for you: the modalities of importing intelligence remain under US control. This is arguably at odds with the first goal: importing a full stack is much less attractive to a middle power than importing components – the US retaining control means you get less sovereignty out of the deal. That makes for a less attractive sales pitch. Why is a mercantilist US insisting on full-stack exports regardless?

One way to make sense of this is to think of US-owned datacenters with US-owned models running on them as a modern-day treaty port. In the mercantilist era, great powers jealously guarded the modalities of exports, limiting export rights to their own domestic traders and banning the involvement of foreign intermediaries. That trend culminated in trade being carried out through chartered company forts, and even later treaty ports: outposts outside of your own empire, in which your own laws and provisions still fully applied. Yes, your wares were shipped and traded somewhere else, but you always retained substantial control over the conditions of this trade. Exporting a full AI stack, completely owned by US companies, serves a similar purpose. AI is being serviced globally, but the US keeps square control over both the cultural and security-relevant aspects of its frontier AI: It retains ultimate oversight over the conditions of its models’ training and deployment, and can interfere with the modalities of its use e.g. in foreign militaries. Of course the host countries could expropriate the datacenters if push came to shove – but that’s a substantial escalation.

Following the chartered fort analogy, the UAE deal starts fitting into the picture. The deal as written does not empower the UAE to do much of anything; it basically places a sophisticated US-owned operation in the Emirati desert and quite literally makes the Emirati pay for it. As I’ve written elsewhere, the UAE of course has some ways to spin the deal into leverage. But if you take it at face value, and assume that there will be another 10 deals like it – as I’m sure the admin does –, it also serves as a keystone precedent for the establishment of US-controlled chartered company forts. If you think the realistic alternative was Chinese GPUs or genuinely foreign-owned datacenters, you can see why a mercantilist US would prefer the gulf deal without needing to resort to cronyism as an explanation.

Export Volumes, National Security & the H20

Third, the administration seems willing and happy to export quite a lot of previously restricted goods. On mercantilist merits, this makes a lot of sense – if you only really export to your friends (and only 100k H100s each, as the diffusion framework suggested), you’re not going to cover a lot of ground in terms of AI exports. In fact, an ardent mercantilist would only refrain from exporting obviously military goods, and introduce nary an export control on basically anything else. The controversial implications of this stance include the administration’s continued exports to countries suspected of smuggling, the general rescission of export controls to not-quite-trustworthy countries, and most famously the ongoing saga around whether to allow the sale of Nvidia’s H20 inference chip.1 I’ll try not to reiterate the broader debate, but the latter serves as a particularly instructive example.

I don’t think that the decision to keep exporting the H20 is primarily the consequence of insidious Nvidia lobbyists, although that often makes for good headlines. I think it also points at two contentious conclusions made by the administration.

The first is: The admin seems to believe the H20 is not a privileged strategic resource. There is good reason to describe the H20 primarily as an industrial multiplier – it mostly helps you to use more of the model you already have (with the thorny caveat that in the age of inference scaling, that also turns out to imply greater capabilities). H20 indubitably help militaries deploy AI – which is why the PLA wants to order them. But grain helps you feed more soldiers and steel helps you forge more cannons, and the mercantilists were still happy to export them, including to foreign militaries. Perhaps the administration is not unaware that the H20 is akin to forging steel, but simply draws the line further up the scale of immediate strategic relevance.2

The second is: Mercantilist doctrine requires defending market shares even at your strategic detriment. One of the ways to stay in the lead on exporting is to artificially ruin foreign demand for sovereign supply by undercutting the market with more competitive offerings. Past inklings of this strategy might already be part of why Chinese chips keep lagging behind. The CCP knows this and is struggling to meet that strategy. It keeps trying to force Chinese companies to use Huawei chips to increase demand and break free of export dependencies, but they keep falling short. Even the fairly new 910C can’t keep up with Nvidia's H20. That fact is highly favorable for the US, both on strategic and on global terms: Strategically, as long as China remains dependent on the US for inference imports, engaging in open conflict is less attractive for the CCP. Without a steady stream of inference chip imports, the US might quickly overtake China on diffusion and deployment. And it’s favourable globally because as long as the Chinese market does not create enough demand for Chinese domestic production of competitive inference chips, China also doesn’t have the chips to run an undercutting export strategy to compete with US compute exports elsewhere. For both the narrow China aspect and the broader global scope of the mercantilist strategy, stopping H20 exports is very risky – even if you do acknowledge critics’ points about H20’s actual value to the PLA.

There are some good answers to all these points, and even then I’m sure these are not the admin’s only reasons for exporting the H20. But I believe they make for a much better explanation for the administration’s stance than a lot of mediocre public defenses that have become the frequent target of dunks and rebuttals: I suspect the admin also knows that Nvidia’s business interests motivate the telling of wild and inaccurate tales; and so better rebuttals instead address reasons why the admin is exporting H20s anyways.

We’re in for much more of the same export control conversation in the coming years. Nvidia is already gearing up to produce ever more circumvention chips like the H20. Engaging the admin on the virtue of controlling future chips successfully depends on understanding what motivates the White House to keep endorsing the export of strategically valuable, but not directly frontier-pushing hardware.

Global Fallout

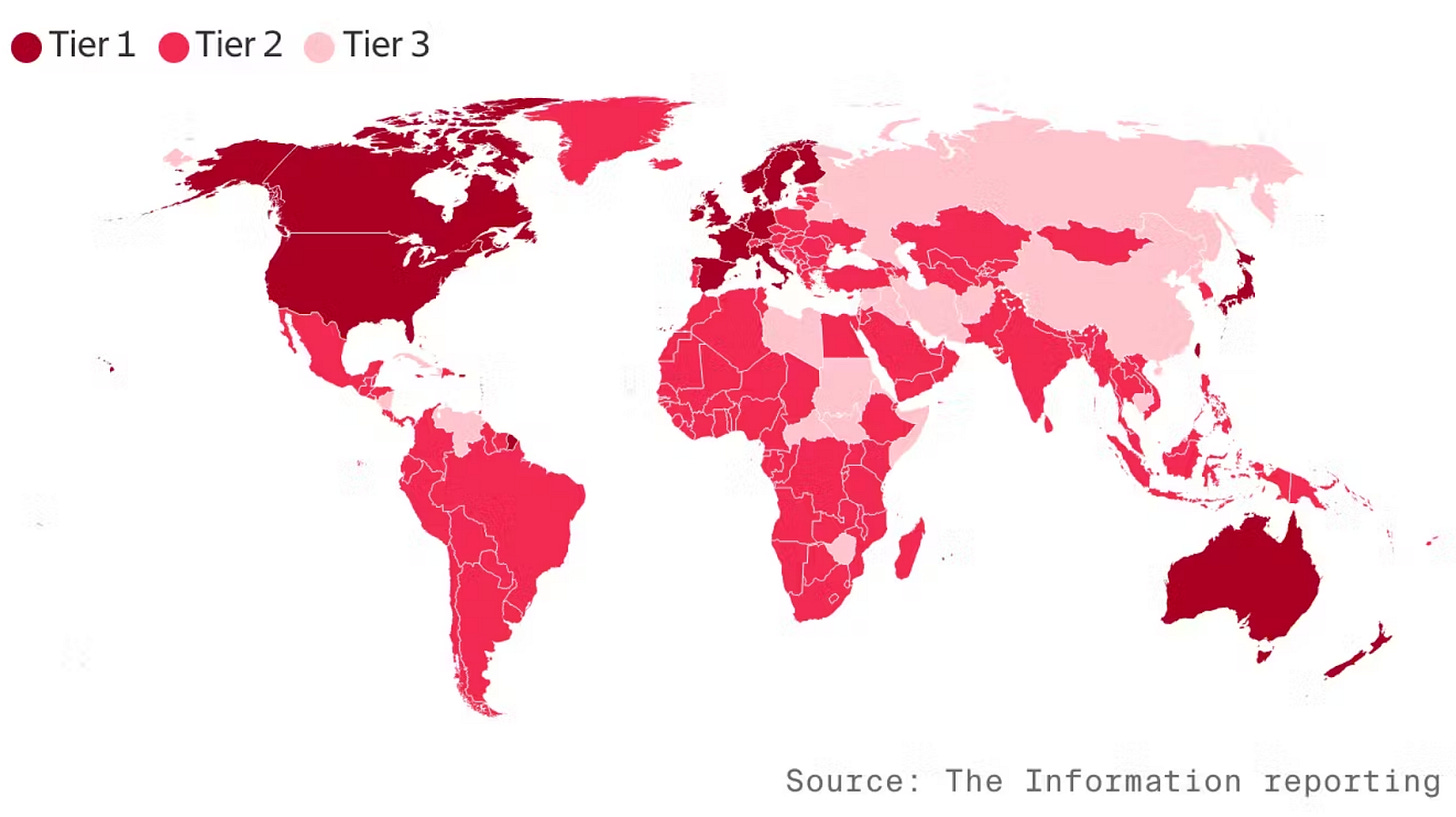

So much for the retracing. What to make of it? For now, I’ll refrain from evaluating the mercantilist stance from the perspective of US grand strategy – others are better placed to do so anyways. But to wrap up, I’ll look at some repercussions in one of my focus areas: the AI strategies of ‘AI middle powers’, advanced economies without their own sovereign AI stack. The effect on middle powers is double-edged, but I believe ultimately positive: With a mercantilist US, you can partake in frontier US capabilities – but you have to buy them.

The fact that middle powers have to buy their way into frontier capability reinforces a critical question: what do they have to offer in the age of artificial intelligence? What bottleneck do they occupy, what comparatively advantageous contribution do they make? In the mercantilist world, these questions need an answer rather sooner – you will not be provided frontier capability cheaply or out of charity, and so you better find a sustainable way to acquire it soon. But in any other world, too, a middle power would have had to find a niche at some point to keep up; and so I don’t think mercantilism is particularly harmful there. To be sure, it takes away some comfortable privilege from the former tier-1 countries, which under the Biden-era framework had some advantage solely through privileged access to US compute. But I think these countries are rich enough to make do.

On the other hand is the massive reassurance that you can buy your way in. Middle powers’ access to US frontier capabilities is much less contingent on sometimes opaque strategic considerations. Access doesn’t depend on Five Eyes membership, it’s not as jealously guarded as nuclear proliferation. That makes the situation unequivocally better for all the countries that have something to offer economically, but don’t have as much established rapport with the US. Poland or India, famously tier-2 in the diffusion framework, come to mind.

A mercantilist US also makes AI geopolitics as a whole a less volatile. I have repeatedly written about the volatility-inducing effects of asymmetric AI diffusion, where one country is about to get advanced AI and the other doesn’t, and that creates incentives for rushing into conflicts, mass migration and even preventative strikes. A more level playing field constructed by a US that maximises export share lowers that risk by opening more avenues to participating in the frontier.

I’ve mentioned that China in particular does not remember mercantilism fondly, calling the age of chartered forts and later treaty ports the Century of Humiliation as it was stripped of its economic and strategic integrity.3 Does the new mercantilism run the same risk for today’s middle powers? Yes, to some extent. A mercantilist US will mercilessly play its hand, and leverage its dramatic technological leadership to its own advantage. Adjusting to that fact will come as a bit of a shock to many middle powers – and it seems clear that they won’t run the show in the AI age. But middle powers aren’t quite as much at the US’ mercy as the colonised powers had been at the original mercantilists’ mercy. Today’s middle powers themselves are highly industrialised and competitive economies – if they play their cards right, they can still play for an ambitious equilibrium in a US-led world. More on that soon.

Outlook

If you follow my reconstruction of the administration’s policy, I think you should consider two takeaways – one domestic, one foreign.

First, I think the many well-informed critics of the administration’s AI foreign policy should refrain from primarily characterising it as erratic and myopic. To some extent it is – to some extent, every translation from doctrine into policy is –, but engaging on its merits and doctrinal fundamentals is, I think, much more promising. In discussing the H20 and whatever comes after it, it might be worth it to engage more clearly on the underlying disagreement about the strategic implications of exporting general force multipliers. If you have a strong opinion on gulf exports, there might be value in taking seriously the prospect of not exporting sovereign stacks, but retaining company-fort-like control. A bit more generally, I believe an interlocutor in a policy debate is best addressed by taking their motivation seriously: Generally, the admin is a little more in the know than some observers credit. And even if it was not, it would be smart to treat it as if. Export control hawks’ communications might resonate better with the administration if it engaged more clearly with its doctrinal underpinnings.

Second, I think the international discussion should take the administration’s export stance more seriously, and capitalise on its upsides. Yes, it makes true sovereignty – whatever that might mean – even less attainable for middle powers. But it makes genuine frontier access a lot more reliable. In a mercantilist world, you don’t get to build truly sovereign datacenters under your own jurisdictions. But that costs a lot of money and might be strategically unsound anyways. The administration’s mercantilist stance invites and compels middle powers to find their niches elsewhere – to find something to contribute to a world run on abundant American AI. Taking this prospect seriously, and realising how much of a departure it is from 2024’s paradigm in technology strategy, should be central to middle powers’ planning.

For better or for worse, I think the Trump administration’s ambitions in AI foreign policy are best understood as following the mercantilist playbook. If critics miss the point, their objections won’t find much purchase. And if middle powers miss the plot, they might find out why China still remembers the Century of Humiliation.

To wrap up the H20 discussion specifically, I will note that there seems to be a way for the mercantilists to have their cake and eat it, too – an excellent piece by Lennart Heim and Janet Egan suggests renting out H20 capacity might be most promising, and I agree.

The fact that it’s now also fleecing Nvidia for a strategically irrelevant part of the export cost then counts as a nice little upside.

Many former colonies of course also don’t remember that era fondly – but I think that’s more about colonialism than about mercantilism.