How To Grow Too Big To Fail

When AI developers overplay their strategic indispensability, they risk undermining pro-AI policy writ large

In the 1770s, the British East India Company went from bad to worse – growing obligations in London and mismanagement in Bengal marked the end of its profitable heyday. For the British Empire, its collapse would have not only meant financial ruin, but a marked loss in British Imperial capacity for trade and administration on the new frontier. Britain recognised as much, and quelled concerns with massive subsidies and protective acts. Failure of its champion was not an option to the mercantilist government.

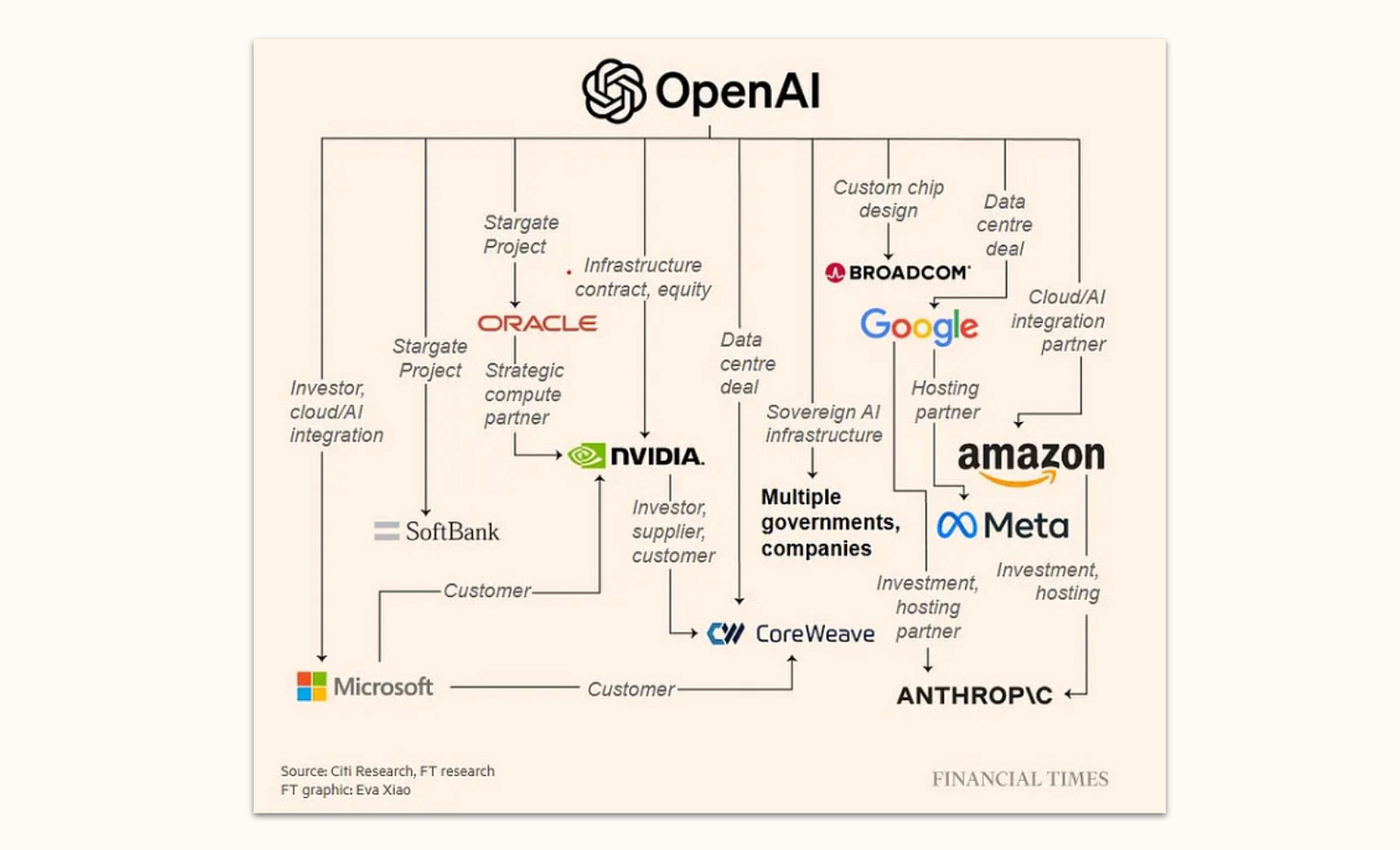

OpenAI, in its own fashion, aims just as high. In an attempt to capture the value of the AI revolution wherever it might accrue, their business is rapidly expanding. Searching for a durable moat, OpenAI is expanding into country-level infrastructure deals, chip design, and partnerships all throughout the American economy – fueling a months-long AI-driven stock market rally. At a valuation of $500 billion, observers were starting to wonder whether OpenAI is on the road to become ‘too big to fail’. Bailout or not, the failure of the leading AI developers was beginning to feel unthinkable.

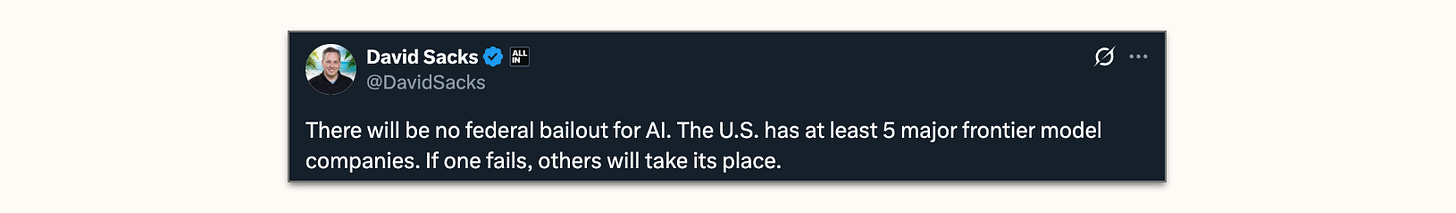

Then, a few weeks ago, OpenAI CFO Sarah Friar said the quiet part out loud: in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, she floated the idea of a ‘federal backstop’ – hinting that the government might step in should OpenAI’s financial momentum falter. The idea was reined back in by CEO Sam Altman, but not before White House AI Czar David Sacks clarified a bailout wasn’t on the table. That particular chapter was open and closed in a few days.

But the story does not end here: AI developers continue to grow, deepening their entrenchment in the broader economy. It’s still in their strategic interest to trade on the prospect of being ‘too big to fail’. The resulting political strategies sit right on the edge: sometimes they’re in pursuit of a genuinely important policy to boost technological progress amidst intense geopolitical competition, sometimes they’re in pursuit of drawing regulatory moats in an emerging market. If developers veer into the latter, they risk spoling the politics of the former.

So there’s a triad of questions worth addressing in the aftermath of recent debacles: what is OpenAI’s path to become too big to fail? Will it work? And what should we make of it?

Why Become Too Big To Fail?

To understand what OpenAI does, it’s useful to start with what it needs. Why would they want to become too big to fail? I don’t think it’s primarily to set up an actual bailout. It’s always nice to have a fallback, of course. OpenAI makes a lot of risky investments, and it would of course be great to get bailed out if they fail. But I don’t think that’s the main point – I’m not sure you ever recapture the spark or regain public and investor trust again, bailout or not.

But short of a bailout, OpenAI greatly benefits from the impression of being too big to fail. The first reason is that it makes for a great policy argument. As I’ve written in some more detail before, AI developers require favourable treatment from the government to stay on track. As written, America’s frameworks are not conducive to a technological revolution: its legal institutions would hamstring data use and bury developers in litigation, its energy infrastructure could not sustain the necessary buildouts, its permitting systems would not get the chips online in time. Both the Biden and the Trump administration have worked to reduce these barriers in their own ways. Without those interventions – and were they to cease – AI progress would slow or exfiltrate to other, often rivaling, countries.

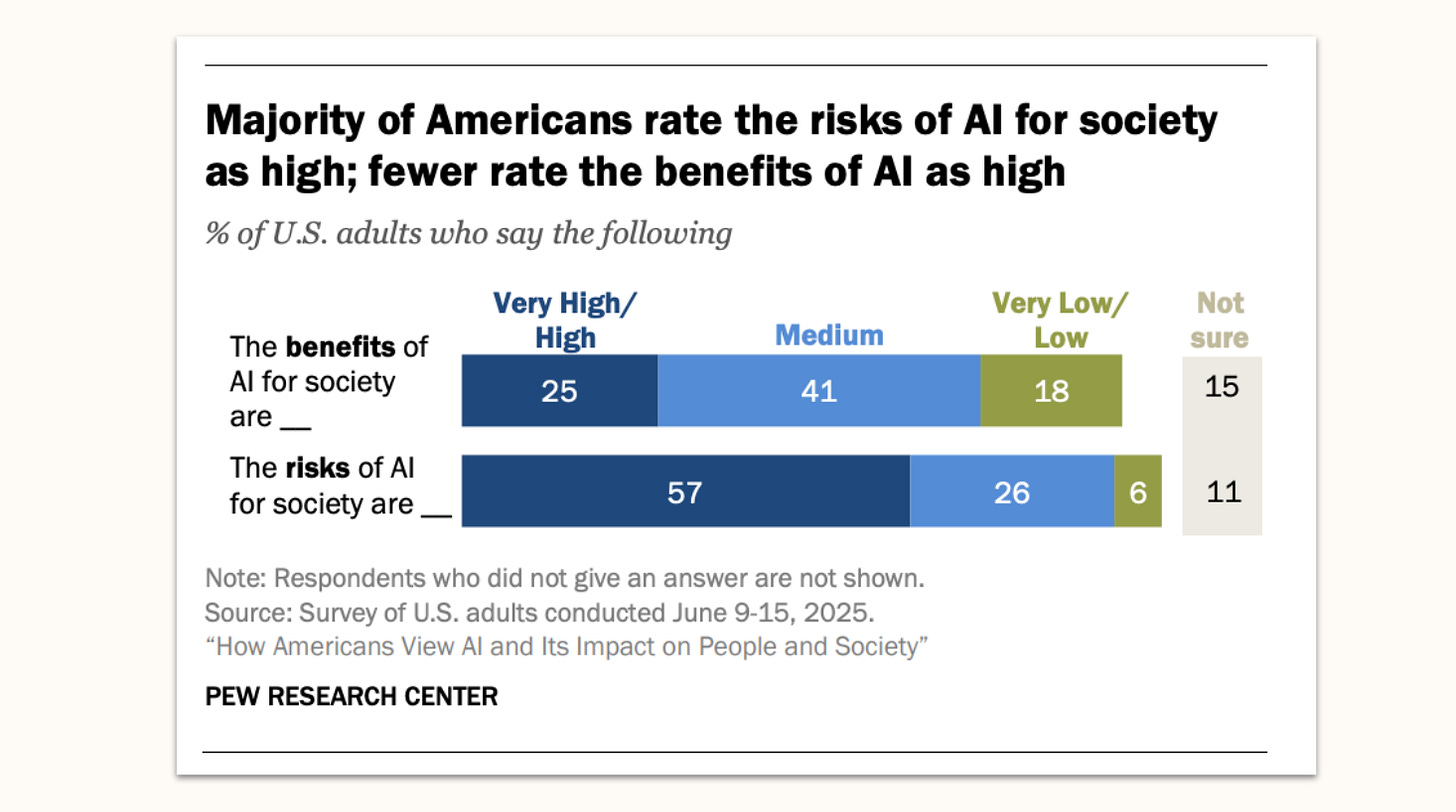

To keep this support going is getting harder by the day, as anti-AI voices backed by abysmal polling are starting to doubt the industry and the government’s support for it. President Trump has frequently been quick to cut loose partners he deems to have grown burdensome. The ‘too big to fail’ story helps to ward off that prospect. ‘Do you really want to preside over a huge stock market crash’, goes the story; ‘do you really want all these companies we have deals with to go under’, it continues; ‘do you really want to be stuck with the bill if we default?’, it ends. OpenAI has a lot to gain from growing big enough to raise the cost of ending government support for AI. In leveraging this, OpenAI sometimes flirts with a line: sometimes, it speaks for the entire industry, calling for copyright extensions or datacenter permitting; but sometimes, it appears to ask for special treatment amidst its competitors, such as in the ill-fated backstop saga. The former is necessary, the latter concerning.

A second advantage of the ‘too big to fail’ impression is that it surely helps with securing all these deals and funding arrangements. Datacenter business is notoriously risky, and country-level partners in particular have been burned a lot by assuming hyperscalers would follow through, only for the risk profile not to work out. Big funding sources, too, like assurances. If you were weighing a big investment of some kind into OpenAI, but felt dismayed at the bubble talk – would you not be reassured to open the Wall Street Journal and read that OpenAI was guaranteed a bailout if things went sideways?

The Making of a Narrative

The impression of being ‘too big to fail’, partly a natural outgrowth of political economy and partly a crafted posture, rests on three pillars.

The first is a deep connection of the AI boom to the enormously favourable stock market of recent months. The rally is driven by tech stocks running hot on the prospect of a new industrial revolution and the reality of unprecedented infrastructure buildouts. This President in particular takes political pride in a favourable trajectory – and for good reason: while stock market performance is not a perfect predictor of political sentiment, a stock market crash is political poison for any incumbent. If OpenAI was to falter, faith in the overall AI rally could soon follow, and policymakers will do their best to avoid that.

The second is OpenAI’s deep, deal-based entrenchment with powerful actors. The most-noted part of this landscape are the many private-sector deals involving creative financing schemes to enable datacenter projects, buildouts all along the semiconductor supply chain, and preferential adoption deals with American legacy corporations. But a lot of foreign governments are likewise putting their faith in OpenAI, banking on the OpenAI for countries initiative to deliver them everything from software to large-scale infrastructure. Either way, deals create stakeholders invested in OpenAI’s survival. If needs be, they might make that case to the government as well – and suddenly, policymakers are not only looking at the prospect of a tech company going under, but at a large section of the American economy heading into a downturn. Deals can create linked vulnerabilities, and thereby further advocacy on OpenAI’s behalf.

The third pillar is the increasing value of AI as a fundamental utility, both as an economic input and a strategic resource. This is where some nuance is called for – because the fundamental argument is right: it’s in the unmistakable interest of America and the West that US firms remain at the frontier of AI development, and that there exists a funding and regulatory environment that allows us to see this technological leap through, even if it comes with some financial and potential risk. Even financial derisking – ‘backstops’ – has an important place in that.

I don’t think it’s nefarious lobbying for AI developers to suggest the same, though of course the incentives align nicely. The trickier question is whether needing AI means needing OpenAI. Not directly, to be sure, as David Sacks has pointed out. But indirectly, it does seem difficult to see how OpenAI could fail and the rest of the industry would still survive, both as a consequence of the collapse of the deal landscape and of general economic sentiment. OpenAI’s contribution to this third pillar, if anything, has been its ability to become near-synonymous with the AI industry as a whole. That makes disambiguation that much harder: even if you stick to Sacks’ tenet of ‘we don’t care about OpenAI, just about AI’, it’s hard to see how you could make that practical distinction.

Taken together, these three arguments provide a vibe and an argument to go with it: skeptics will be assuaged by the sense that ‘surely, the USG won’t let OpenAI fail’, and OpenAI can continue to wield the implicit threat of ‘better make sure to keep us afloat, or else…’.

The Quiet Part Out Loud

The Friar incident is a major setback to that trajectory. That’s why I struggle to believe it was some sort of clever test balloon testing how far one could push this. OpenAI was trading on the implicit notion that it was too big to fail. But in the wake of Friar’s comment, even unrelated OpenAI proposals – such as a call for derisking chip manufacturing or expanding AMIC credits to the AI supply chain – were quickly miscast as a bailout plays by uncharitable critics, tainting sound and helpful suggestions. Making the notion this explicit also invited clarifications – in this case, latent opposition from within the GOP led the White House to clarify a bailout wasn’t on the table, and Sam Altman to walk back the very idea.

No harm done? Not quite, because a bailout would be much more difficult to achieve in the future now – and the observers that were supposed to be assuaged by the prospect have taken note of that shift. The bailout has grown more unlikely for multiple reasons: Now that a senior OpenAI executive has publicly mentioned a bailout as an option, it’ll be harder for OpenAI to insist that they’ve always argued in good faith and never planned for a bailout, should it become necessary. Now that critics are alarmed, it’ll be harder to subtly further the impression of ‘too big to fail’. And now that the administration has committed against a bailout, much helpful ambiguity has been lost.

Why It Might Not Work

Let’s nevertheless assume people mostly forget about the Friar mishap and things cool down again. Is OpenAI’s strategy working out? Is the growing impression that it might be ‘too big to fail’ justified? I think there are three factors that still greatly complicate this story.

The first reason is: large firms aren’t given bailouts because of their market capitalisation, but because of their political relevance, either in terms of jobs or of strategic value. In the 2008-2009 case of automakers, the story was jobs: Michigan is a politically important state, the automakers employed many workers, and the bailout was very good politics. Comparatively very few people work for OpenAI, and most of them in electorally peripheral California. The Lockheed bailout in 1971 is of the strategic value kind: Lockheed was critical to military-industrial capacity, and couldn’t be allowed to fail. You might make the same argument for OpenAI or the AI industry at large today. But if a bubble burst, the sentiment on that would likely shift, too. Believing in the strategic upshot of AI requires believing in claims of future progress in capabilities and adoption; but a bubble burst that would require a bailout could be read as evidence to the contrary. ‘If AI was important enough to warrant bailing-out, why did it not even meet its revenue projections?’, the story would go.

The second reason is: many assets tied up in the ‘AI bubble’ are relatively easy to reabsorb. If things went sideways, the value currently tied up in AI would not evaporate. Much of the capex is prospective to begin with: it’s in forward commitments for datacenters that haven’t been built, purchasing contracts for GPUs that haven’t shipped, and talent acquisition that hasn’t been paid out. Even the assets that have already taken physical shape – the current generation of datacenters – are fungible and absorbable. I’m sure we’d find a second-best use case for all the talent and especially all the compute even without OpenAI.1 Granted, once the valuation for all these assets was cooled down a bit by a market correction, the reabsorption into the overall economy wouldn’t be perfect by a long shot – a lot of valuation of the infrastructural and talent assets in particular would be lost.

But a bubble bursting would primarily be bad news for the committed institutional investors; it does not spell a widespread loss of real assets in the way that past sectoral failures would have. If the automakers collapse, the still-depreciating manufacturing plants’ value actually plummets, and they could only be repurposed at great cost. An AI bailout isn’t as necessary to ward off a similar loss in non-fungible assets.

And the third reason is: AI and its developers are still very unpopular. A bailout, of course, would likewise be unpopular. So unpopular, in fact, that it could become a liability to a White House that delivered it. Already today, Presidential hopefuls and dissident voices within the GOP are positioning as anti-AI; Josh Hawley and Ron DeSantis are perhaps the most visible examples. An economic populist platform on the left is likewise just one sharp pivot removed from a very promising anti-AI strategy; and I suspect the midterms will give us plenty of data to reinforce these strategic directions. The Trump administration, and presumptive candidate Vance in particular, is already visibly tied to AI through its policies and relationships to tech executives – but an all-out bailout is more visible still. If AI continues to be as unpopular as it is, no shrewd politician would want to be on the record for sustaining it even where the market would not.

For all these reasons, I’m skeptical that a bailout in the current market and political climate was ever really in the cards. But that’s the easy part – recall that OpenAI’s primary hope was always to trade on the prospect of the bailout more so than to secure the bailout itself. This is perhaps where the Friar incident hurts the most: implicitness was a boon in this debate. Now that people are making the bailout conversation explicit, the gaps in the pitch for the bailout are starting to show, the political economy starts showing its teeth, and the implicit prospect becomes so much harder to keep alive.

Where This Leaves Us

I’m not excited to collectivise the risk of OpenAI’s specific business strategy. But I’m also wary of the political fallout hindering important avenues of government support. As so often, we’re left with a potentially unsatisfying middle road, on which it’ll be important to keep two things in mind at once:

There’s a real incentive for OpenAI to become too big to fail, and we should work to calibrate the market so that governments do not bear the risks of OpenAI’s individual business. Given the chance, major players will always be tempted to kick away the ladder once they’ve gotten to the top, and doubly so in a business as politically entrenched as AI. That’s normal, but being watchful of this natural trend is both good and the measure of a healthy policy ecosystem.

But we can’t cross the line into overscrutinising the idea of supporting and derisking AI progress and buildouts as a whole. We need smart policy mechanisms to do this – otherwise we won’t be able to sidestep the often-atrophied mechanisms of Western democracies to stay in control of this technological revolution, and we won’t be able to proliferate this technology throughout the world in time to ensure an equitable and stable order. The government simply has a role to play here, and it should be enabled to play it well.

All sides can contribute to this – as always, our worst political instincts are to dunk on our pick of power-hungry AI companies, Luddite politicians, crony capitalists or captured regulators. It bears repeating again that this is seldom helpful, and takes us further away from the nuance we need to make difficult disambiguations like the above.

But an immediate burden to do better falls on OpenAI and fellow developers. They already greatly benefit from a USG that has the leeway to derisk AI buildouts as a whole. Support for AI is already effectively support for OpenAI, especially if OpenAI is optimistic about its relative position in the AI race. Anything OpenAI does to suggest that government support is a tool to secure its relative competitive position, rather than to advance national progress, actively undermines that broader project. That’s ultimately not to OpenAI’s advantage. As AI grows, so will the temptations for AI developers to exploit their proximity to power for short-term gain. To keep AI policy on track, they need to resist.

I do wish someone would do some research on what exactly the best and most likely use of current compute buildouts would be in case there was a market correction