Three Fault Lines in Conservative AI Policy

The Right must find out what 'winning an AI race' means, how much jobs matter, and who to trust.

When the Biden administration introduced its controls on the diffusion of advanced AI chips, many observers on the right found themselves in agreement: The US was ‘winning the AI race’ by leveraging its technological leadership to stay in the lead, secure alliances and force concessions. When AI Czar David Sacks recently walked back the diffusion framework, he too spoke of winning such a race—by doing exactly the opposite. He received much criticism, but there is a more interesting lesson in this contrast. Come game time, abstract terms like ‘winning races’ do not cut it anymore. They mean anything and nothing, and provide little action guidance. Fault lines in AI policy on the right need addressing soon.

In many ways, making AI policy on the left is easy. Political ideology left of center features a baseline pro-regulation impulse and skepticism of big technology corporations. It also emphasizes allegiance to international cooperation, labour unions and civil society special interests, as well as commitments to distribution and social justice, all of which slot very well onto the AI discussion. At the intersection of these commitments, the political left has not yet encountered a major directional question in AI policy that genuinely had it stumped for a policy response.1

The situation on the political right is quite a bit more complex. A nascent field of right-wing AI policy is just coming to terms with the scope of current technological progress and its ramifications. The Right’s baseline impulses on AI – loyalty to small government and skepticism of tech corporations, to retaining US jobs and strategic supremacy – don’t always align well and sometimes clash. To make matters worse, the current coalition is plagued by tensions between factions with radically different views on technology. And so it needs to clarify its substantive positions on AI while torn between urgent practical political consideration – and fast.

Figuring out what positions should imply is very much an ongoing effort, which is usually code for making it up as one goes. Sadly, we don’t have the time for an ‘ongoing effort’: The American Right is presiding over a moment of extraordinarily high technology policy leverage, and so it has a fairly unique chance to shape the trajectory of advanced AI. I think there’s three issues in particular where an emerging right-of-center vision of AI policy still has substantial gaps: defining a ‘victory’ in the AI race; dealing with AI labor disruption; and developing an approach to big AI companies. This is an attempt to clarify these gaps, motivate some discussion, and set up progress on addressing them well.

What Does Winning the AI Race Mean?

It has become GOP consensus to endorse the goal of ‘winning the AI race’. I suspect this general phrase conceals substantial underlying disagreement: at the very least, major GOP players seem to mean different things when they invoke a race victory. I think there are at least four competing understandings of what ‘winning the race’ means: Military, diplomatic, economic and cultural.

Military Victory: In the style of ‘Situational Awareness’, this scenario entails locking down and nationalising frontier development. A USG-led project would ultimately develop highly advanced and strategically decisive AI systems. Victory takes the shape of decisive military supremacy. My sense is that very few people within the administration currently take this view, but it’s closely implied in some influential AI policy work, e.g. by Leopold Aschenbrenner, Eric Schmidt and Dan Hendrycks.

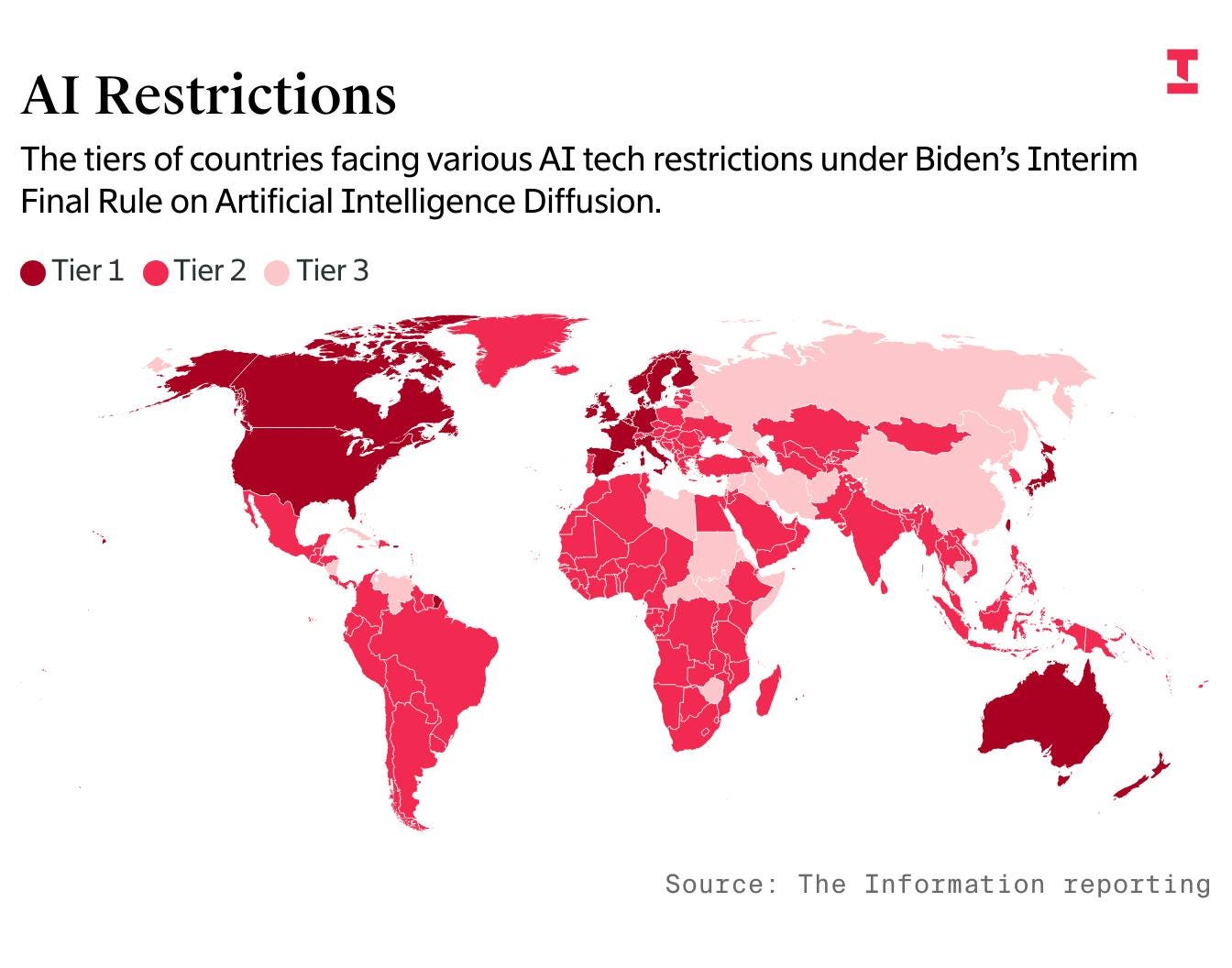

Diplomatic Victory: Domestic policy focuses on support of frontier AI development within a fairly open market without nationalisation; foreign policy focuses on leveraging frontier advances and the overall value chain to maintain a decisive technological advantage, leverage concessions and favourable conditions. Victory takes the shape of de-facto technological hegemony leading to massive economic and political leverage. I take this to be the founding theory of victory behind the Biden-era diffusion framework.

A similar notion might also inform future, analogous diffusion rules for model weights or even API access to US models in the future. This perspective is perhaps most consistent with existing US dogma – it mirrors the approaches that have been taken with regard to most other strategic technology that emanated from the US, from nuclear weapons to advanced military aircraft.

Economic Victory: Similar to the previous scenario, domestic policy focuses on unleashing domestic AI development and deployment. But dissimilarly, no substantial constraints are applied to exports and imports. Victory instead takes the shape of massive economic growth on the backs of exports along the AI value chain. I think this is the notion of ‘AI race victory’ that best explains David Sacks’ recent comments on scrapping the diffusion framework in favour of winning the AI race – a decision that seems actively counterproductive to the above theories of victory.

Cultural Victory: US-built AI models are cheap and good enough that they become the de facto standard on which most of the world operates. Victory takes the shape of global promulgation of American values through the proliferation of US-built AI systems. It’s similar to the economic scenario in that the primary pathway still runs through an unconstrained free market. But it’s dissimilar in that there is less immediate economic benefit to it: To make the US models ubiquitous, they cannot be particularly scarce, or outcompeted on price by e.g. Chinese open-source models. As such, US AI capability might be provided open-source or at least abundantly cheap. I think this is the notion of victory invoked e.g. by Marc Andreessen or Mark Zuckerberg. It’s expressed in plenty of fervently pro-open-source writing on the broader matter, but it also mirrors the history of the internet: while the internet has been a remarkable tool for cementing global US hegemony, it was never steered or leveraged directly by the US government.

Sometimes, these notions of victory can be combined: For instance, you might combine the economic and cultural scenario by selling frontier model access at high prices and proliferating open source capabilities freely just below that frontier. More often, however, these notions conflict. Today, the most salient instance of such conflict is between national security and economic interest and relate to controls on compute diffusion: Do diffusion controls help win the race because they maximise US leverage over who occupies the frontier, or do they hurt because they bar the US from capitalising on great compute demand today? For now, the more laissez-faire factions on exports seem to have prevailed.

But this disagreement is unlikely to be the last such conflict. The ostensible shared goal of ‘winning the AI race’ is currently glossing over a lot of deeper disagreements on the Right, because it gives very different positions a common expression. The required policies will diverge again and again: for instance once AI systems become capable enough to provide substantial strategic value and therefore raise questions around controlling their diffusion. At many technical inflection points to come, debates will break out – because the GOP is not substantively aligned on what needs to be done to win an AI race, or what that even means.

How Much Job Disruption is Progress Worth?

Advanced AI is likely to have substantial impacts on the labour markets as a necessary corollary of becoming generally useful: AI developers are pouring most of their development efforts into models that are good at independently executing complex task sets in a way that seems highly conducive to automating away many junior white collar jobs. Along the tracks of the current technological paradigm, ‘a lot of AI progress’ is therefore almost necessarily linked to ‘a lot of labor market disruption’. That fact introduces a substantial tension to right-of-center AI policy. Increasing technological progress and minimising job disruption are founding tenets of one element of the GOP coalition; but you can’t have both in the long term.

Dealing with the prospect of these disruptions requires threading a political needle even today. You have to acknowledge the challenge in serious tones, otherwise there’s risk of creating a difficult impression: GOP political leadership is focusing its communications on denying the prospect of broader displacement. I believe the top of the Republican party is acutely aware of this problem. It’s the reason Vice President Vance’s AI message is so strongly focused on jobs and affirming the potential positive impacts. It’s why his interview preparation seems to include arcane tales of job creation through automation, as was obvious in his recent conversation with Ross Douthat. And it’s the reason why President Trump felt obliged to touch on the job creation through the Stargate datacenter initiative he announced on his first day in office. Already today, when a senior administration official talks about AI, they try to get ahead of the wave and talk about job creation.

“But I just think, on the economic side, the main concern that I have with A.I. is not of the obsolescence, it’s not people losing jobs en masse.” — Vice President Vance

But that’s dealing with the prospect of job disruptions and the politics that prospect creates. Dealing with the reality, once it does come around, will be much more difficult still. Assume that in a few years, leading AI developers really do roll out agent systems capable of automating basic service tasks and junior white collar roles. Their diffusion will be a matter of massive political importance. Will policymakers decide to put up barriers to diffusion, smooth the shocks of labor displacement and resulting political upheaval – but risk harms to AI developers’ financial viability and strategic advantage? Or will they keep their hands off, ensuring US AI gets the economic integration needed to stay at the frontier – but risk a political open flank to displaced workers and many others scared to join them?2

The conventional political arithmetic would have a governing coalition favour the former approach and save the jobs: surely, there are more votes in being good on jobs than being good on strategic tech policy. The MAGA base especially is motivated in substantial part by economic populism; a promise to protect and provide old jobs at modern pay. Volatile labor markets and uncertain job futures go directly against that promise. As a result, I think the Luddite reaction is the default outcome; and I worry that it could happen without a lot of nuance. If the political incentive is strong enough, and the opposition is too disorganised, backlash can be violently jarring, and lead to hasty introductions of barriers that ultimately prevent a lot of AI’s promise.

On the other hand, plenty of incentives point the other way. The first is that the ‘tech right’ influence within the modern GOP still runs deep. Recent media reporting oversells rumours of alienation: The sometimes strained relationship between Silicon Valley CEOs and President Trump is taken pars pro toto for a re-alienation between tech right and GOP. I think this is the wrong read: what matters about the tech right is their influence on the intellectual traditions of top officials like JD Vance, their donation money, and the broader electorate of younger voters it provides. None of these seem at great risk today.

As a result, I suspect there will be at least some 2028 hopefuls willing to bite the bullet on job disruptions to appeal to the tech right part of the coalition. Whatever remains of the old-school national security environment probably follows a similar tendency: AI is the one rising strategic technology that the US retains a decisive advantage in. Any threats to this supremacy, even in a free market paradigm, is a threat to the US’ geopolitical competitiveness. This kind of argument doesn’t usually perform well at the polls, but it could sway some party leaders to take the anti-Luddite position; igniting conflict at the very least. Such conflict will not be resolved without a fight around how to trade off jobs and AI progress – and the Right has not yet found a standard by which to adjudicate it.

What To Make Of Big Tech Companies?

There are a lot of important decisions to be made in how to develop and deploy advanced AI systems. These are questions on research directions: between agentic independent systems and more sophisticated tools; between narrower experts and broader generalists; between artificial coders and artificial friends; between military assets and economic engines. There are questions on deployment: at what safety levels to deploy, at what capability thresholds to halt, what use cases to enable and which capabilities to hold back. Some of these questions are questions of public policy; but most of the Right agrees that public policy should not attempt to answer all of them in last detail. Who else, then, makes these decisions? The default answer is: free market participants who build these technologies, in response to market dynamics. But the AI developers at the frontier are all big technology corporations – with whom the Right has a strained and complicated relationship.

On the one hand, political tradition suggests the Right might be skeptical of letting tech corporations take the reins on AI. The ‘tech right’ emergence last election cycle does not extend to all top brass of Silicon Valley – in fact, many GOP decision makers have remained quite skeptical of many tech CEOs’ ostensible pivots. To place the decision-making power over advanced AI in the hands of the same companies – even people – that only years ago had been derided as the bastions of peak wokeness seems like a stretch.

On the other hand, it’s hard to find an alternative steward of the AI revolution. What to do if you’re wary about an AI paradigm driven by technology corporations? Any more fundamentally decentralised paradigm seems unlikely: the requirements in terms of capital and talent agglomeration make distributed ownership of AI very difficult and strongly favour development and deployment through a select few major players. This is especially true if you’re opposed to enforcing diversified distribution through hard top-down regulation. There is no real option to be loyal to a free market of small and scrappy American businesses – letting competition run its course means agreeing to the tech corporate paradigm.

Endorsing the government stepping in and growing big enough to encompass key decisions on AI development is ostensibly a left wing answer, but in today’s time, it might horseshoe around all the way to the Right as well. This is a sentiment that is prominently at display in the curious phenomenon of right-wing supporters of ex-FTC-commissioner Lina Khan. They, like their left-wing counterparts, take a highly skeptical view of agglomerated corporations. This caution is not only due to market-distorting effects of oligopolies; it reflects a deeper distrust over the powers these corporations wield over public discourse and is a relic from the last years’ contentious ‘fact-checking’ programs and censorious social media algorithms.

But a big government response to the challenges of AI is, of course, politically and normatively fraught as well. Defending against government bloat and overreach is a core political tenet on the Right. Giving the government sufficient capacity and interface to actually steer frontier AI development means giving up on that tenet at least in the context of AI. There’s some precedent for that; the government does steer some central strategic technologies like military industry or nuclear power. But AI is, in many ways, much more personal. It extends into personal relationships and private businesses, into many citizen’s information diet and social interaction. Reneging on the libertarian impulse in the context of ubiquitous AI systems cuts much closer to the ideological bone.

What will the Right make of this tension? Perhaps letting tech corporations take the lead still comes most natural – especially to an administration that takes pride in its good relationships with CEOs, tech and otherwise. Corporations' good graces with the administration often rise and fall with the relationship between their CEO and President Trump. If that relationship is good, it’s easy to imagine the President endorsing sweeping corporate power over AI through reference to the good character and trustworthiness of a figure like Elon Musk or Sundar Pichai.

Lately, this relationship has been rockier than before – but in an hour of mutual need, it still seems plausible that Silicon Valley leaders would redouble their efforts to win the President’s favour and thereby the mandate to lead a corporate-first AI order. Still, plenty of voices on the Right perceive these corporations as shadowy and unreliable actors, and their leaderships as shifty and not-quite-trustworthy. Once the transformative potential of advanced AI hits home, perspectives on who should steer it will clash.

In that moment, this third question would need an answer: Does the government dare to expand beyond the classical liberal’s impulse and interfere with the development and deployment of advanced AI? Or does it shrink back and leave the field to tech corporations’ leaders despite their strenuous relationship with the political right?

How Not To Proceed

Faced with questions like these, ostensibly well-meaning policy advice attempting to address politics right of the center usually makes one of two mistakes. They’re worth naming and avoiding.

First, a lot of contributions to right-of-center AI policy amount to ‘concern trolling’: They take a left-wing position for granted, and then express their concern that the Right does not share that position. ‘I worry that the Right has no plan to incentivise AI developers to prioritise my political pet issue’ is not a helpful contribution at all. Useful contributions have to take the underlying values and commitments seriously and not take the end-state for granted. Too often, AI policy on the Right gets conceptualised as ‘reluctantly making left-wing policy while obsequiously waving American flags’. That can’t be it.

Second, on the other side of the spectrum, a different kind of unhelpful contribution just alleges that important gaps are actually coherently covered already. This often takes the shape of statements like: ‘The President is very clear about this-and-that’. This is somewhat reminiscent of recent trade policy discussions, where different factions on the Right rushed to clarify that actually, the President was planning to alternatively keep the tariffs or roll back the tariffs, or either planning to weaken the Dollar or strengthen the Dollar. That’s a very good way to advocate for your particular view, but it glosses over the underlying disagreements in an ultimately unproductive way.

I try to avoid both failure modes above. I hope further discussion - mine and others’ - of these issues can do the same: We are in urgent need of strong contributions to the unsolved questions around how right-of-center values and commitments relate to governing advanced artificial intelligence.

Outlook

It falls on the political right to meet the political moment of steering the development of advanced AI. It must rise to the occasion so that we don’t squander the promise of getting AI right. To get ready for that, we need to make progress on these three questions now.

Although here, too, the story gets more complicated as soon as you factor in more moderate center-left voices that place more value on reaping the benefits of technological progress soon

Maybe this is not entirely a dichotomy. But at the very least, I believe it politically presents as one.