A Strategic Case for H20 Chip Exports

Retracing the argument for exporting inference capacity

These days, most reasonable observers seem to agree: Nvidia’s H20 chip – powerful computing hardware used to run frontier AI models – should not be exported to China. Yet the Trump administration has cleared it for export. Why? The common answer is that the administration is supposedly deeply captured by Nvidia’s business interests. Confusing public interventions by Nvidia and puzzling administration statements have added fuel to that fire. The result is a very unsatisfying policy debate that had led to export proponents simply calling their adversaries doomers, and an increasingly incredulous opposition baffled at the administration’s choices.

But this framing misses important nuance. There is a strategic logic under which a serious U.S. government might choose to export inference chips — not (only) to enrich Nvidia, but to preserve a fragile equilibrium. US policy has so far targeted frontier AI capabilities, but not broader economic growth and development in China. Banning inference chip exports visibly breaks with established doctrine, shifting focus toward limiting deployment in China. That risks provoking China into erratic action. But if you think that America is currently winning the ‘AI race’, you might prefer not to rock the boat.

This piece reconstructs the strongest version of that strategic case, along with its potential shortcomings. It’s not to say I necessarily think the H20 should, on the whole, be exported. But there’s value in retracing what I think is the best argument in favour of the exports: I think it can provide for a better understanding and more helpful engagement with the administration’s choices. And perhaps recover some nuance – if only to prepare for the next debate over inference chip exports.

A Doctrinal Shift

Today’s China-focused export controls, downstream of the initial framework of 2022’s CHIPS act, have a narrow aim: Disrupt Chinese ability to pursue frontier AI capabilities. Banning the export of the H20, which is not primarily read as capability-increasing chip, departs from this underlying doctrine. Therefore, the argument goes, export bans risk upsetting the strategic equilibrium and with it our current, favourable trajectory.

Inference is (Still) not Training

The H20, by itself, does not enable the development of frontier models. It is a (remarkably capable, top-tier) chip for servicing inference, i.e. for deploying and improving already-pretrained models. Of course, the lines blur in today’s technical paradigm, which has model capability scale with available inference compute and allows large RL-driven improvement, but puts less emphasis on pre-training alone. It’s inaccurate to say that the H20 only allows running extant models; it does help improve and customise models to pursue specific tasks, and can be used to boost their overall performance. But still, the fundamental strategic distinction, one that informed the development of the H20 to begin with, remains: If you export only H20s to an adversary, they don’t have the silicon to build a competitive frontier model. In that important sense, it remains a chip for deployment, not development.

And beyond the technical facts, the H20 is still a chip designed, branded and sold as focused on inference — which matters for strategic perception. As a result, banning H20 exports is a visible departure from past US doctrine. The CHIPS act and subsequent communications implied a clear American policy: To prevent China from building its own frontier AI, but not from overall growth and progress. Inference chips bans instead send a different message: Chip export controls will no longer be leveraged to exclusively target frontier development, but also include economically valuable AI deployment. Maybe that is the right message to send, maybe not – but it’s different in an important way.

By all accounts, the CCP has been outraged and hit hard by the original export controls. Still, by now, China’s AI ecosystem has accepted the CHIPS act doctrine and its narrow focus on national-security-relevant frontier development capability: Chinese strategy does not count on importing US-designed training chips, or on importing Western semiconductor manufacturing equipment. China is instead moving toward sovereignty on its own frontier AI stack. One major contribution to this equilibrium has been that there was a credible understanding that China would not be seriously hindered from deploying AI to fuel its own economy. In fact, even ‘hawkish’ top Biden officials have sought to avoid sending that message; it was not the policy of the US to target overall Chinese economic growth. Perhaps partly in consequence, China’s AI strategy as per the recent AI+ plans aims strongly at the deployment of AI systems throughout its economy – a strategy that requires few frontier training chips, but runs on the wide availability of inference capacity. The current equilibrium in international AI policy depends on that mutual understanding underpinned by the original scope of 2022’s export controls.

“What we're focused on is only the most sensitive technology that could pose a threat to our security. We're not focused on cutting off trade, or for that matter containing or holding back China.” — Antony Blinken, then US Secretary of State, in Beijing, 2024.

Two Paths Only

As AI grows increasingly more important, and for the time that the US retains its lead, the doctrinal choices bifurcate more and more clearly: Either you stay narrow and target frontier development; or you go broad, implying a doctrine of targeting Chinese economic growth. That’s because AI deployment becomes increasingly difficult to divorce from general economic considerations: more and more economic sectors will depend on it. This is particularly true given the current Chinese approach to AI, which identifies diffusion and deployment as the central objective. Restricting inference threatens this overall approach to economic policy very directly. Put differently: If the Chinese plan is to use AI in every business, hitting deployment capacity necessarily means hitting the Chinese economy at large.

As a result, the logic that justifies banning the H20 signals a departure towards a broader doctrine of export controls. As a Chinese onlooker, you’d be justified to wonder: If inference capacity is targeted now, what other elements of the deployment strategy might be next? For starters, there are other non-frontier-training chips that can turn out important to Chinese AI deployment efforts, such as RTX Pro chips used in advanced manufacturing. And similar criteria seem likely to apply to other resources just as well: API access or electrical infrastructure, for instance, also enable the deployment of AI throughout the Chinese economy. Now, I’m not saying all exporters of the H20 are likely or obligated to suggest these export controls as well. I am saying that a decision to not export the H20 communicates a willingness to diverge from established doctrine, in a step toward more sweeping controls that target the Chinese economy.

Rocking the Boat

Entertain the notion that China might understand inference export restrictions as a doctrinal shift for a moment. China hawks might be tempted to dismiss that, arguing that China is already operating adversarially. But the argument does not require a dovish view. Instead, you might like the way things are going in the US-China race right now, and not want to rock the boat. Sticking to established doctrine would be a path to maintain a favourable strategic dynamic. And there are some reasons to think the AI race is going well right now – both from a US and global perspective:

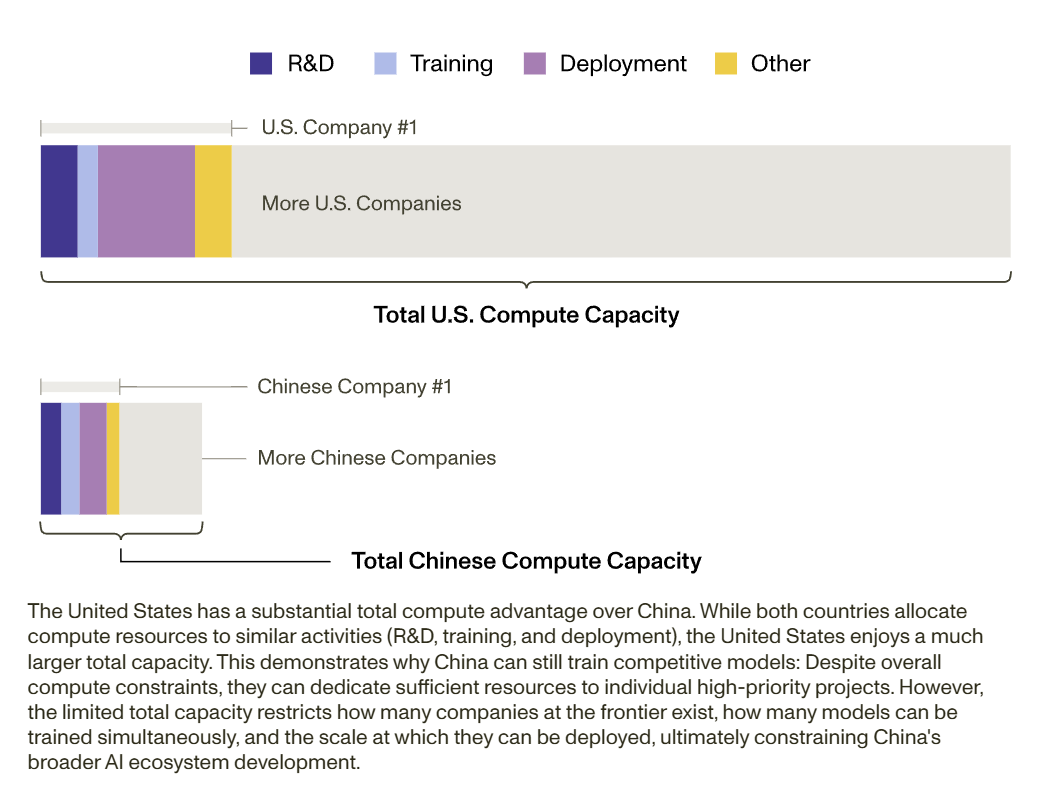

America is Winning

First, you might think the race going well for the US, which still holds a sizeable lead in frontier model development and frontier chip design; as well as a commanding starting position for the race for global diffusion. Even datacenter infrastructure and open source competitiveness, two often-invoked US weaknesses, have gone fairly well lately. Especially if you follow the administration’s logic and believe in the flywheel effect of globally proliferating your superior AI stack, you would think things are generally going very well.

You might not share that optimism, for instance because you think that today’s favourable position is due to greater access to frontier chips, and exports threaten that. Perhaps you’re right — for now, I simply want to say: it’s worth noting that parts of the administration do feel optimistic about the state of affairs, even if you don’t agree. It matters for understanding the logic behind their policies.

More narrowly, you might also think that continued Chinese use of Nvidia inference is actually good news for the US – because it delays a tightly integrated hardware-software stack in China at least for some time. On the administration’s logic and by many technical accounts, tight-knit integration between chip design and software on one hand and model development and deployment on the other hand quickly leads to accelerating capabilities. Setting up a full Chinese-built stack would hence be strategically valuable in the mid-to-long term. But as long as US-built inference chips remain available, Chinese companies’ short-term interests will push to use them over Huawei chips: right now, Nvidia inference chips are still clearly better. This sets back some Chinese efforts of software-hardware integration by as long as they keep using Nvidia inference instead.

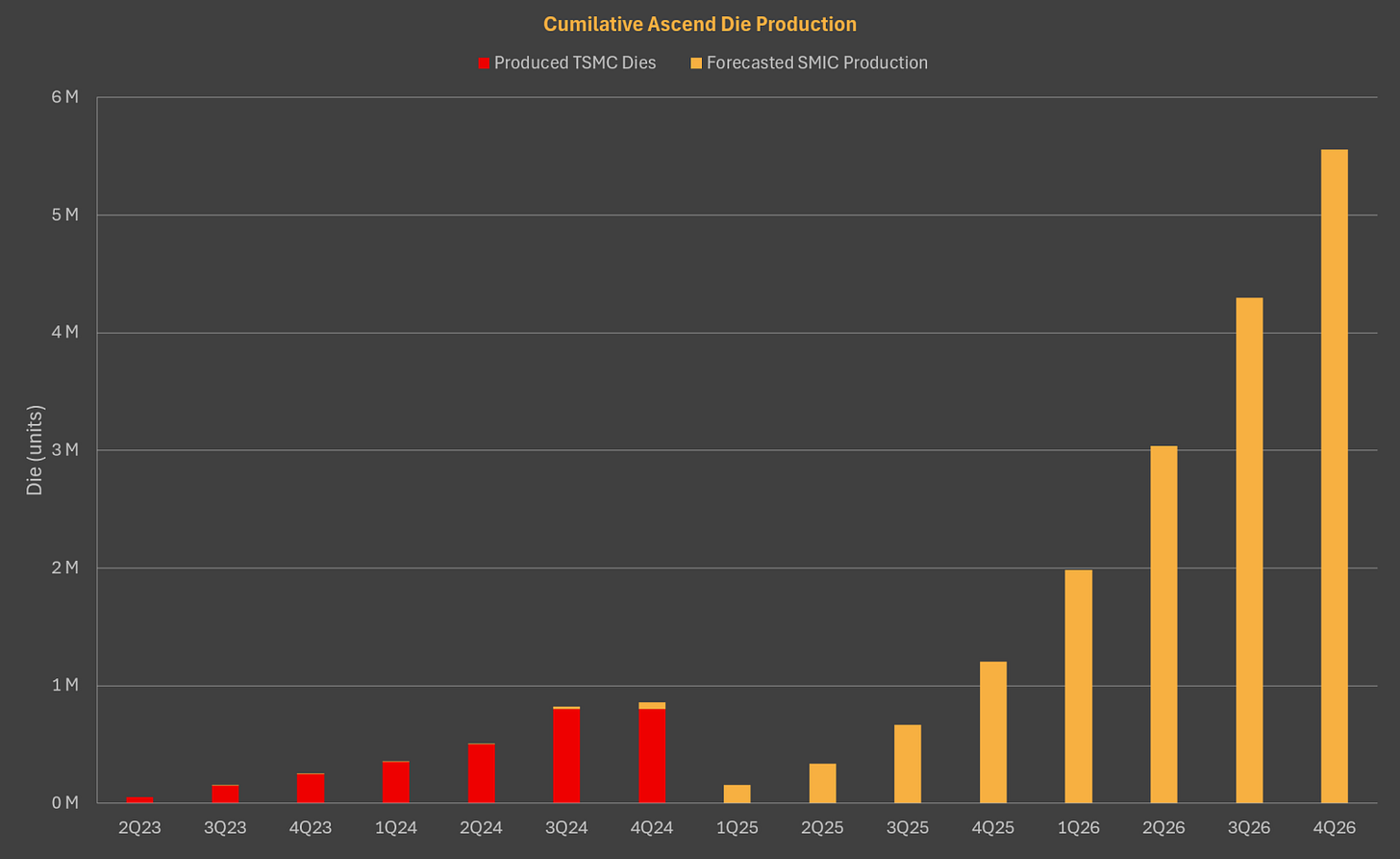

Importantly, none of the above has any substantial bearing on Chinese capacity a couple of years down the road. Experts largely agree that sooner or later, Chinese semiconductor production will ramp up so China won’t be strapped for inference supply anyways. Export decisions largely don't affect SMIC's trajectory toward servicing domestic demand– ramping up semiconductor manufacturing is a core strategic objective, and Chinese buildout will ultimately happen no matter how much you export. So, we’re mostly talking about a few transient years of Nvidia-fueled Chinese inference either way.

The chip ecosystem tradeoff is therefore this: Do you provide more inference capacity to China now, setting back meaningful hardware-software-integration by some time and thereby reducing the potency of Chinese-built chips once their production comes fully online? I think depending on how valuable you think current diffusion is, you can come to different conclusions on that question. I tend to think that current deployment is really not all that valuable, and delaying Chinese software flywheel effects by supporting Nvidia-run inference could be a win in isolation.

Why is China doing this, then? My best guess is that they’re making a mistake, driven by their AI champions’ short-term interests. It’s a mistake the CCP is trying to fix by encouraging use of domestic semiconductors, but for now, they’re still making it. The export proponent’s credo is simple: let them.

The Best Version of the Race

Second, you might also think the AI race is going well for everyone. I’m partial to this view: the race seems mostly economic and diffusion-focused, with a limited extent of securitisation and state ownership, and no likely military culmination in the near future. We seem to be set for a great power competition that produces AI systems available for market rates, not security clearances; and it seems likely that we’ll be able to somewhat effectively diffuse the benefits through long-established mechanisms of technological progress. That was not inevitable.

In the current setting, we’re spared many of the worst versions of the AI race that had analysts worried. We see relatively little securitised secluded development, lab-internal-only deployment, hasty integration into military structure, rampant sabotage and supply chain disruption. We’re in a strange situation where both participating great powers seem to believe that the economic version of the race is best for them. Perhaps one of them is mistaken, perhaps it’s actually positive-sum. No matter, I get why you’d think this is an equilibrium worth maintaining.

China Can Flip the Gameboard

All of this can quickly change once you change doctrine visibly enough to prompt China. Current Chinese strategy, formulated post CHIPS act controls, would suffer from a broad US export control regimen. Deployment-focused plans would not survive contact with an aggressive US effort to restrict AI-diffusion-driven economic growth, beginning with the H20 and plausibly threatening to include further important goods. A lasting shift of US doctrine to that effect would ring alarm bells.

As soon as the CCP is faced with the realistic prospect of an aggressive, deployment-focused export control scheme, it’ll be prompted to react. How? Arguably, the CCP has no magic way to redouble its efforts in the economic AI competition: It is already aiming its strategic capacities at increasing AI capacity and fostering deployment as much as it can. So if they had to react to a threat to the deployment strategy, China might feel inclined to shake things up.

I don’t know how that would look exactly. I definitely think it would make all the disruptive ways for an AI race to play out more likely again. Plenty of frequently-discussed drastic policy actions from China could suddenly be acutely on the table. On AI specifically, perhaps coordinated sabotage of US efforts, leading to a more securitised setting; or a state-run AI development effort prompting a similar state-run American competitor. On broader policy terms, perhaps a hastening of plans on Taiwan prompted by fear of asymmetrically increased military AI adoption in the US; or an extension of controls on rare materials or legacy semiconductors. The predictive details are unclear, at least to me. I’ll just say that it seems unlikely that China would do nothing, and that there are plenty of escalatory levers it has not pulled yet. Any way in which China could attempt to flip the gameboard threatens the ways in which the AI race is going well right now.

If you think that the current state of the race amounts to slowly, effectively choking off the Chinese AI ecosystem and its global influence, you’d do quite a lot to reduce any source of volatility. If exporting inference capacity is what it takes to reduce the risk of radical action, then you might think that’s a price worth paying.

It’s a tricky balance even today: Recent back-and-forths around export controls have already endangered the strategy, leading to Chinese government warnings against use of the H20 and an outright ban of the RTX Pro 6000D. A strong reiteration of the American commitment to inference exports might still remedy the fallout — perhaps.

A Better Doctrine?

Is there a way to frame the H20 decisions in a way that doesn’t give the impression of departing from the frontier-focused doctrine? Some suggestions have been made to that effect.

The Total Compute View

First, perhaps pursuing frontier capabilities should be understood in a broader sense: Exporting the H20 frees up existing capacity in China to be used on other things; for example by freeing up smuggled training chips that currently have to be used to service inference to be used on training instead. The broadest version of this view has given rise to a ‘total compute’ model, in which the key objective of export controls is to keep China under a certain threshold of compute. Could that be a way to retain a narrow compute-focused doctrine without giving the impression of targeting overall growth? It might be, if AI was a fairly niche phenomenon. But, as established by many policy documents and executive orders (all of them read in China, no doubt), the US government believes AI is a core economic driver of the future, and compute is the substrate on which it runs.

At the same time, China has repeatedly, publicly laid out that it seeks to use a large amount of compute for general integration. That makes it hard to sell a total compute view as a narrow technical stance. To develop policy that limits the substrate of economic growth is likely to be read as limiting China’s overall economic productivity. Again – perhaps that is the right call, especially in light of China’s diffusion-focused strategy; perhaps you otherwise lose the race on deployment, no matter how good your models are. But arguments in favour of switching strategies seem to undersell the magnitude of the shift. A total compute strategy aimed at diffusion and deployment is not remotely the same thing as the past frontier-focused strategy. It would be a big step with meaningful strategic implications.

Renting Out Inference

Second, you might argue that not exporting the H20 does not mean strapping Chinese inference capacity – because you’ll just rent out H20 capacity instead. I really like this suggestion, and think it makes for an elegant response to much of the current policy noise. But I still think, from the Chinese perspective, it makes for unsatisfying consolation. If you do believe in this outsized importance of compute for running your economy, you don’t want your inference to be serviced from datacenters abroad, to be switched off at a moment’s notice.

In some sense, the ‘renting H20’-proposal is a good mark of why it’s valuable to retrace the strongest version of the pro export argument: Renting is a very good solution if the issue is ‘how do we ban exports while allowing Nvidia to still make a lot of money’, following the cronyism view. It’s somewhat less effective at solving the problem if it’s ‘how do we not rock the boat that’s taking us across the AI race finish line’, because it does pose a challenge to current Chinese AI strategy.

The Chinese Exports Problem

That said, I do think there is a weighty argument against H20 exports on the administration’s own logic: They enable a Chinese export product. One of the greatest threats to the market-share-focused, ‘flywheel’-inducing AI foreign policy strategy is a competing export product. If China develops an exportable stack itself, it can compete with the US, undercut prices, threaten global software lockin and more – thereby threatening the US negotiation position for export promotion as well as the value of getting these exports right.

But China’s export stack will have to be Chinese-built compute; otherwise it’s no viable competitor, is not under full Chinese control, and doesn’t cash in on the same flywheel merits as the US product. But it seems unlikely that China would prioritise using its home-built compute for exports if it was still struggling to meet inference demand at home.

This domestic demand will be serviced by a mix of domestic and Nvidia chips. So for any H20 exported today, you free up one comparable Huawei chip for export in the future. On the mercantilist, export-focused US perspective, exporting the H20 still hurts: not because it’s particularly useful to China or harmful to US interest, but because H20s free up Chinese chip production to build an export product. One of the big reasons why the US would be favoured in the current version of the AI race is that it’s first to the global export party: the US stack can proliferate while China struggles to meet domestic demand. Relaxing this constraint on China by exporting H20s threatens to undercut US advantage in the export race. If that happened, you might suddenly be less optimistic about whether the US leads the race – and might have to reconsider your H20 strategy as well.

Outlook

All this is a very specific chain of arguments that requires accepting a host of contentious premises: around the current shape and trajectory of the race, about America’s odds in that race, and about the likely development of Chinese AI ambitions and strategies. But by many public accounts, the current administration does accept these premises. If you agree, I think it’s not too difficult to follow them to the conclusion of exporting inference chips — especially if you factor in the revenue gains that surely play a role as well.

That said, I’m still not quite sure if any of that means exporting the H20 is a good idea. For one, I do think enabling Chinese exports is seriously opposed to the administration’s agenda. And beyond that, trading off the above arguments against the many good points made in favour of restricting exports is very difficult, and certainly beyond the scope of this post.

But I don’t mean to persuade you one way or the other - but to invite you to consider an alternative explanation of the administration’s current decisionmaking. For detractors, that might mean focusing their spirited objections elsewhere: on the export argument, on the tradeoffs between giving China more inference now or a more integrated stack later, or on explaining why China’s reaction to a strategic change would not induce volatility.

A more doctrine-forward conversation around this question might ultimately also be in the interest of export supporters. At least, I’m not sure how tenable it is for the administration to continue offering very few substantive comments on the export strategy, and let the void be filled by Nvidia’s PR antics instead. I remain convinced that somewhere within this discussion on the H20, there’s a real debate to be had.