The Real Sycophancy Problem

Transparent political opportunism can hurt frontier AI policy on both sides of the aisle.

Toward the end of the last year, a lot of people working on frontier AI policy were faced with a double shock: A drastic change of the AI-political landscape following the reelection of Donald Trump as US President; and a reconfirmation of predicted rapid AI progress following the release of reasoning models and the associated inference scaling paradigm. Reflecting on these shifts, many came to a remarkable conclusion: The deployment of advanced, transformative AI systems might occur during the second Trump administration.

On the policy side of the advanced AI discussion, rapid AI progress had until then been a fairly abstract concept. This radically changed as the meaning of ‘a few years until advanced systems’ began to imply ‘within this administration’. This came as a shock: Many organisations in frontier AI policy — developers and thinktanks, advocates for safety and progress alike — had either tailored their message to the Biden administration, been left-of-center to begin with, or simply prevailed because their message better fit the moment of 2020-2024. Because AI policy had only become a major subject during that time, its players had not yet grown used to the cyclical nature of US politics. As a result, much AI policy seemed ill-suited to prevail under the new administration.

Faced with short timelines, a ‘now or never’ sentiment among non-right-wing AI policy organisations ensued: Either you got your platform to fit the Trump administration well, or you might not get a word in before the rapture. As a result AI policy advocates of all stripes are rushing to marry their policy agendas and political framings to the currently incumbent political coalition. Most AI policy proposals these days include at least a stanza or two on how they might ‘secure American leadership, ‘beat China’ or ‘ensure American supremacy’.

In plenty of cases, this pivot is justified and effective — many frontier AI policy organisations genuinely fit well with the GOP platform, especially at the intersections with issues of national security, government efficiency and economic growth. These organisations can and should drive that political fit home. But in many other cases, these attempts are a transparent narrative stretch with great costs to credibility and policy development down the line. Looking ahead at the coming years of strenuous policy battles, this sort of political sycophancy has little promise in the short term and holds much long-term strategical peril. I believe this is true no matter your stance on US politics and the likely effectiveness of the current administration.

Beware the Convert

Adjusting your political framing as an obvious reaction to an incoming administration is not particularly effective. It’s fairly transparent to begin with, and once an administration is already in power, it’s just about the worst moment to be aiming at its political favour. The field of policy organisations vying for political favour is going to be extraordinarily crowded, and any commitments to its political goals seem obviously motivated by political reality. Some organisations realise these challenges and jump at reframings anyways because they believe the long shot is still their best shot. I believe that’s a mistake.

That’s first because transparent opportunism can damage your credibility. The policymakers and operatives that run the current administration are not stupid, and contrary to frequent derisions, neither is the political leadership of the GOP. When organisations spend years singing the tune of onerous regulation underscored by clearly left-of-center values suddenly start employing basic right-of-center narratives, political operatives read the play. To some extent, this is of course a normal part of policymaking. But where the framings get clumsy or reductive, they can often arouse suspicion: Framings can be so reductive that they betray a lack of familiarity or sometimes a borderline disdainful view of the incumbent coalition. They can also be so clearly inauthentic that they cast their authors as needlessly Machiavellian and manipulative.

I think frontier AI policy organisations are prone to misexecuting this sort of messaging pivot. On the one hand, they are often sufficiently shrewd and scarred by past political misfortune to try. But on the other hand, the frontier AI policy ecosystem is fairly young, and has very few people that have extensive experience with or connection to party politics. It instead mostly consists of people who, in the literal and figurative sense, quite recently moved from SF to D.C. to further their agenda. This has a twofold result for the credibility of partisan pivots: They get genuinely much more difficult to execute because the policy organisations have a worse understanding of how to get the messaging and shibboleths just right; and they get more difficult to communicate well because the organisations have no credible ambassadors that can lend their face to a partisan pivot.

In the end, policy organisations can end up much worse off through that kind of move: Before, the administration might have at least perceived them as somewhat neutral experts with somewhat interesting things to say. After a transparent attempt of reframing, they are revealed as overtly political actors — with none of the usual benefits of naive expertise or earnest communications left, and much suspicion gained.1 Of course, that is a needle to thread: a certain amount of political reorientation and adjustment of one’s communications under a new admin are part of the lobbying game. But by and large, current execution in AI policy lacks subtlety and finesse.

Hence, more often than not, authentic civil society organisations and genuinely innovative businesses are not doing themselves any favours through employing shallow narratives, like arguing any kind of quid-pro-quo would be in the spirit of the current administration because ‘Trump is a dealmaker’ or calling any of their projects ‘America First’ just because they happen to take place in the USA. Those who are interested in perusing a broader selection of such attempts might be interested in the submissions to the AI Action Plan’s recent RFP — there are some gems in there. I suspect that in many cases, simply not employing this kind of very obvious framing would be more effective, because not playing politics at all retains some advantages, too: It helps communicate a branding of expert advocacy, of qualified and non-political input. In many policy situations, this standing is a substantial advantage; it especially provides a good position to leverage a potential external ‘wake-up call’. At the very least, a less politically contentious position would be meaningfully more robust to political happenstance and future changes in power.

Beware the Traitor

Opportunism toward the GOP also hurts you on the other side of the aisle. If right-wing alignment is to be successful, it has to be credible – that is, it has to pay a price and make commitments that signal some extent of true allegiance. It is no accident that this price is usually high enough to substantially cost you with other political factions. That is to say: If you thought it was difficult to manage the shift to a GOP-dominated environment these days, wait until you have to pivot back to Democrats after paying extensive lip service and policy adjustment to Republicans for four years. Any political gains from today’s opportunism incur substantial opportunity costs today and disproportionate reputational costs tomorrow.

This is true for two specific reasons. First, Democrats are scrambling for a new, coherent agenda right now. Factional warfare between centrist and left-wing elements for the party’s agenda and ultimately the 2028 nomination is ramping up, and with the politics fights come the policy fights around what proposals will become the next cornerstones. And as it so often happens in two-party-systems, priority policy areas for one party become central to the other party, too, as one party’s focus invites another party’s response. So given the Trump administration’s focus on technology and innovation policy, its visible allegiance and interaction with tech CEOs, Democrats are genuinely in need of a strong alternative policy platform to pit against the tech policy embodied by Vice President Vance and Elon Musk. In that setting, a policy organisation faces real but underrated opportunity costs: aligning with the GOP might cost them their ability to shape the Democrat platform.

The former might harm good AI policy’s case with the Democrats even today: as the Democrats articulate their response, they will look at what they are responding too – and the more they identify elements of prudent frontier AI policy as inseparable with the GOP rhetoric, the more they’ll be likely to reflexively take the opposite position. Second, this is exacerbated by ever-increasing political polarisation. This invites ‘backlash politics’ to the extreme: there is political appetite and policymaker ambition to roll back opponents’ policies and disadvantage their loyalists. If AI policy advocates were successful in closely allying their platform to the GOP platform, they’d still have made the content of their platforms political, and have invited the Democrats to attempt rollbacks and rescissions – much like what happened to most Biden-era AI executive action. I would not expect somwhat sensible Trump EOs to survive under the next Democratic administration any more than vice versa. But that would at least spell intermediary success. Even worse is what I think is the likeliest case: That AI policy opportunists might fail to affect GOP policy, but in trying, come across so right-wing coded that Democrats reject them, too.

Do Democrats Matter?

You might think this is well and true in the abstract, but doesn’t apply to the specific setting of AI policy; either because you think that the current coalition will remain important enough for long enough to bet on them, or because you think only the next few years matter for AI.

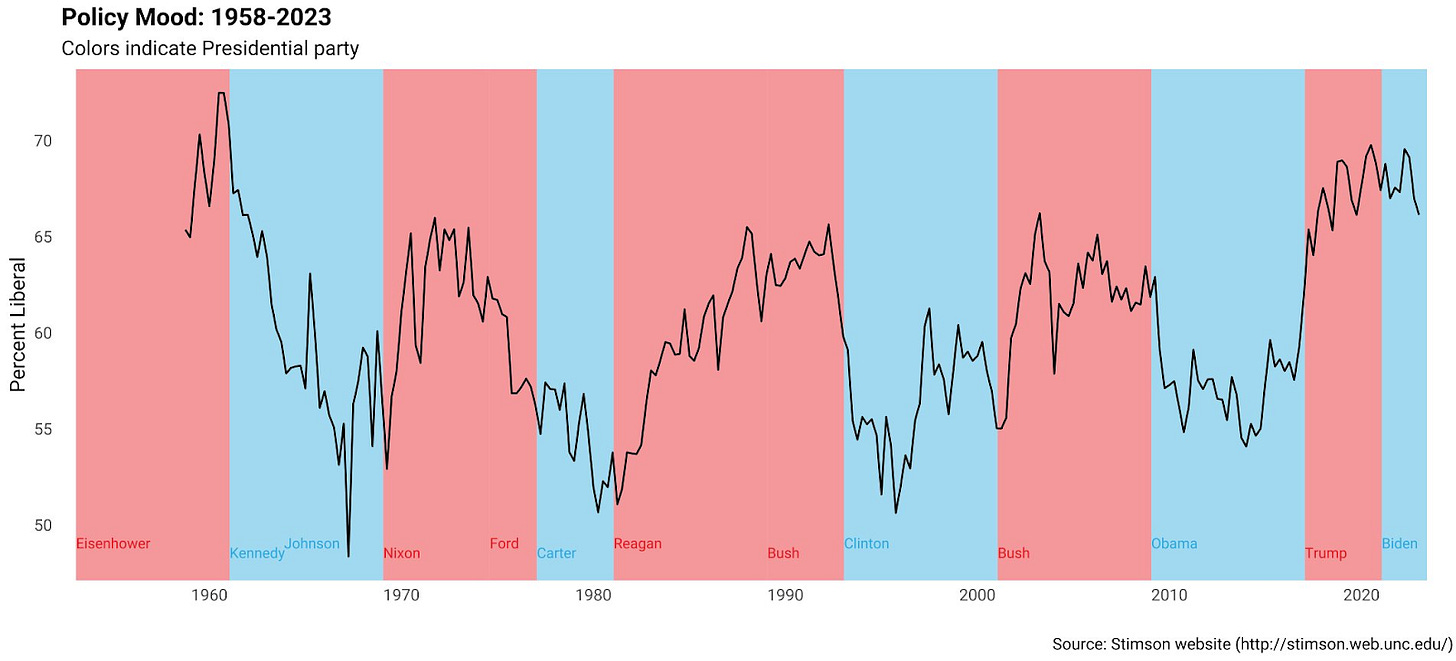

The first is unrealistic: current Republicans aren’t a very safe long term champion for any AI policy platform. For one, they’re a moving target to begin with; it’s very hard to predict what ideas will prevail in the highly heterodox current coalition, so playing to a stable GOP alignment will always be very difficult. Beyond that, the GOP is not unlikely to lose the midterms, and similarly likely to lose the next presidential election, too – as much is a function of the administration’s fairly low approval ratings and the inherently thermostatic currents of US politics. And once they lose, if they lose, there is no saying where the GOP coalition is headed. The current uneasy coalition, from economic populist to ‘tech right’ elements, is drawn together by happenstance and a unique, uncontested leadership figure in President Trump. But happenstance will change as material conditions change and unearth the underlying conflicts in that coalition; and Trump is term-limited and almost 80 years old. No one knows who will prevail in the succession battle for the GOP’s soul, which makes close alignment with the current party a volatile boon.

The second prospect, i.e. that only the next few years of AI policy matter, seems equally mistaken to me. This deserves a separate post, so I won’t go into much more detail, but even if we get highly advanced AI by 2028, there will be a lot of policy conversations to be had afterward; around its deployment, its diffusion, its intersection with job markets, economies, global power balances and human identity. Only on a few narrow and contentious models, such as rapid recursive self-improvement of AI capabilities, does the deployment of advanced systems spell the end of policy. I don’t think a dramatic ‘intelligence explosion’ is likely enough to opportunistically aim for GOP allegiance with reckless abandon. If you disagree with that, you might be justified to dismiss most of my argument—but even still, you might reflect on how far ‘learning to speak Republican’ really gets you in three years.

Politics Cloud Policy

Over time, political sycophancy hurts policy development. This mostly has to do with filtering ideas: Where policy organisations start placing higher and higher priority on the political feasibility of the ideas they play around with, political thinking enters discussion of new ideas earlier and earlier. In some sense, that’s a desirable trend: You want policy organisations to operate somewhere close to overall political feasibility. The problem arises when policy organisations over-index on one specific political setting and evaluate political feasibility accordingly. Simply put: You want a policy organisation to throw out all ideas that are political non-starters altogether, but you don’t want it to throw out all ideas that are political non-starters in the 119th Congress. A strong tendency to go with the political tides strongly incentivises to do the latter.

On a related note, the frontier AI policy ecosystem should also be cautious not to provide cloud cover to suboptimal policy. By endorsing political thrusts that seem promising for a specific AI policy idea – such as overly aggressive jingoism to incentivise taking AI seriously –, advocates can inadvertently contribute to the broader political thrust. It’s important not to oversell this: rarely has a war seemed unlikely until frontier AI policy experts have endorsed it. But still, as AI grows more important, so do the statements of perceived AI experts. Their voices of support can still be employed to justify broader policy currents. For a recent example, just look at the Trump administration’s recent decision to scrap the Biden-era diffusion framework to enable the large-scale export of computational resources to unreliable allies in the Middle East – a move for which they extensively employed the very same ‘we have to win the AI race’ rhetorics that AI policy people have fed into for months. The move in itself goes squarely against most suggestions from frontier AI policy; but the political rhetoric used in its justification is common parlance partly because AI policy organisations were so quick and happy to endorse it.

Implications

Policy organisations in frontier AI would benefit from more realistic self-awareness regarding their likely appeal to the GOP – and regarding the risks of shooting for this appeal but failing. The bitter lesson of AI safety’s recent failure in particular should not go to inspire reckless attempts at pulling apparent levers of political power – playing politics poses backfire risks abound.

To reiterate, there are policy areas where the existing frontier AI policy platform neatly intersects with the administration’s political priorities. On these issues, leaning into this political fit is prudent and productive. In particular, there are parts of frontier AI policy that have long taken a strong stance on Chinese competition, US-driven paradigms or progress and the dangers of overregulation that are great fits with the current administration. There are also policy areas where building out the political alignment to right-of-center factions is worth it; such as when it comes to labour market impacts given the MAGA commitment to the American worker, or when it comes to the intersection with trusted manufacturing. Going down that path can be valuable for some organisations – though as I’ve argued elsewhere, doing so runs more through genuine changes to the policy platform as it does through political framing.

But there are also policy areas that have no strong natural fit with what the administration is trying to achieve. That includes work on less adversarial US-China treaties, diffusion control that is set against narrow commercial interests of US exporters, close NATO integration for model oversight and security purposes, close interaction with EU regulation, extensive oversight over frontier labs and their corporate activities, work at the intersections with copyright and liability, and most work that intersects with what used to be called the ‘AI ethics’ camp. Organisations that prioritise these areas should be mindful of leaning too far into GOP alignment; it’s unlikely to get them very far, and much more likely to hurt them down the road.

Instead, they can continue playing to their strengths and retain the plausible reputation of independent expertise – it’s worse than being on the political inside, but still much better than squarely on the political outside. Or they can join the battle for the Democrats’ future stance and platform, where they might find much warmer reception and greater need for their policy advice. There are plenty of paths worth taking – just as long as you steer clear of the temptation of hasty political opportunism.

The same effect hits pivoting organisations that genuinely do feel closer to the Republican platform, but have simply pretended their Democrat alignment under the Biden era. These organisations’ past opportunism now prevents earnesty today.