AI Policy & Labor Politics

AI agents are coming to the labor market. That fact could reshape AI politics, raises a dilemma for AI safety advocates and threatens the tech right coalition.

Labor Market Effects Could Take Center Stage on AI

Throughout human history, the emergence of viable alternatives to human labor has triggered tremendous political volatility. In the early 19th century, the arrival of the power loom sparked the original Luddite revolution against industrial automation, leading not only to violent protests and military crackdowns, but a broader movement of trade unions and socialist politics that ultimately resulted in the foundation of the Labour party that would provide seven UK Prime Ministers. A century later, accelerating industrial automation in the 1910s and 1920s drove massive urban migration, realigning party platforms and setting the stage for the New Deal's transformative labor policies. The resulting shift in party coalitions lasted well into the 1960s. Today, just about another century later, we’re off to the races on AI automation. What does that mean for the political environment in which AGI is built?

The last couple of weeks have seen the first releases of AI agents – systems that might be able to independently execute some economically meaningful tasks. This is a long-expected watershed moment for AI’s labor market effects: Before, the use of language models served as a fuzzy augmentation of human-led tasks: there was a vague feeling that surely, this would have to have some kind of labor market impact. Deep Research feels notably different. I think almost everyone who’s done junior tasks in knowledge work, be that as a congressional staffer, consulting analyst or graduate student concurs: Deep Research passes the vibe check.

Whether or not you agree with Sam Altman’s specific impression that OpenAI’s Deep Research can fulfil a single-digit percentage of economically valuable tasks – it’s at least enough to start asking questions on what comes on the coattails of AI agents’ labor market impacts. Others have argued the point well, and the jury still seems out on how large the ultimate niche for humans will remain – for the purpose of this post, I’ll assume some displacements will be viable and financially attractive as a consequence of very near-term capability growth. I guess that counts as a conservative estimate these days?

Today’s AI politics are susceptible to substantial disruptions from that. Just two weeks ago, I wrote, as part of a broader analysis of the AGI political economy, about ‘AI longshoremen’, economic incumbents with a large stake in not being displaced by AI.1 Since I’ve made that point, Operator and Deep Research have been released, and some fog of war has lifted – so in this post, I’ll take a much closer look at the specific implications of AI becoming a labor policy issue.

Labor Politics Crowds Out Policy

I believe the labor market issue has the potential to dominate AI policy discussions at large. Compared to non-tangible risks of future catastrophe, to still somewhat fuzzy security implications, even to adversarial foreign policy and geopolitical racing, labor market issues are much more central to the overall political economy, and tend to swallow any issue they become a part of. There’s three structural reasons for that:

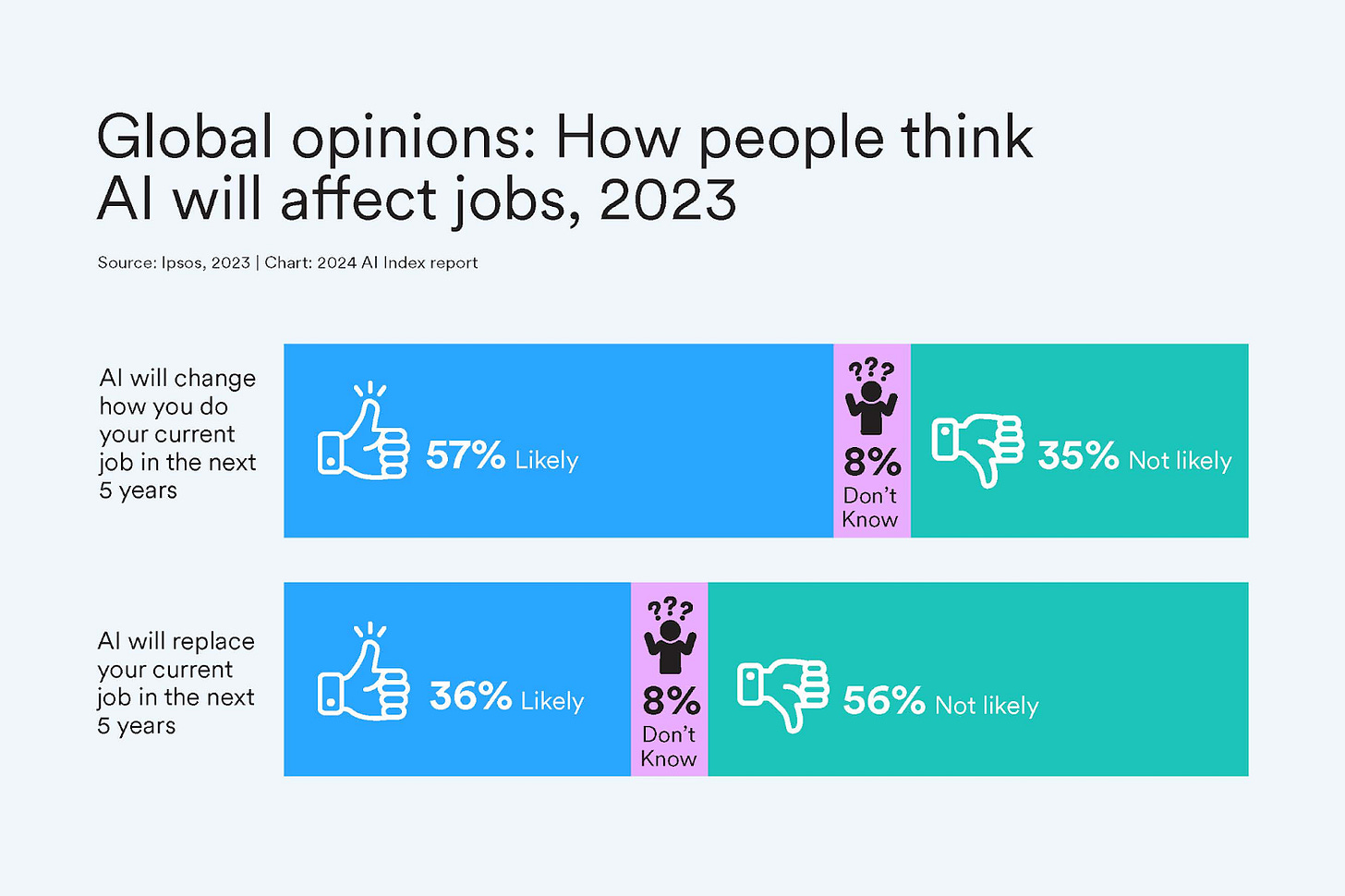

Labor market impacts are incredibly salient to the electorate. Obviously, people can tell when they lose their job, but beyond that: unemployment statistics are heavily featured in news media, and people can tell when others close to them lose their jobs. In that sense, the likely cross-cutting nature of AI disruptions specifically boosts that awareness further: Instead of single isolated regions or sectors suffering from strong labor market impacts that the rest of society can compartmentalize, most people in most places might come to know an example of AI-driven job loss.

Labor market impacts are incredibly important to the electorate. Peoples’ job safety and their perception of that job safety strongly informs their voting behavior; and their economic outlook, which is another highly important political variable, is likewise meaningfully informed by their labor prospects.

Appealing to labor market impacts is convenient and well-practiced. ‘Pro-jobs’ messaging is one of the oldest tricks in the political book for most major political parties, and it has often been a winner. If it seems applicable to AI, an issue that many incumbent governments have linked themselves to, that seems politically attractive.

So, come the first national headline about AI labor market impacts, many established policy blueprints could just be pulled from the drawer and thrown at it. Those could range from negotiating job assurances to hamstringing adoption through oversight requirements to outright banning the use of technology for automatable tasks. In lieu of proactive policy, policymakers could also just pitch cutting back on the political support that helps the current speed of progress: Stop permissive permitting, energy build-out, public-private partnerships, facilitation of investments, etc. These fruits might even hang low enough for political parties to go for this even before labor market impacts manifested at scale.

As a result, I think it’s likely that debate around the pathway to economic adoption and managing labor market effects will be a mainstay of AI policy in the next years. That could mean the first question at every political press conference on AI will be about labor market effects – and not China or safety. This is happening right now: At the Stargate press conference, following drastic predictions around AGI and its overwhelming possible effects, after Larry Ellison of Oracle and Matayoshi Son of Softbank promised paradigm-shifting changes to science and productivity, repeated journalist questions addressed job effects and unemployment risks.

Likewise, the shift could mean that the first headline about new AI releases will be about which sector the displacements hit next. It could mean that foreign policy priorities around AI are largely shaped by steering disruptions instead of strategic interest, that domestic AI economic policy is increasingly bundled with measures of labor and social policy, and that faster speed of AI development is widely perceived as at odds with the short-term interest of working people.

Any policy agenda that is not readily related to these issues could take a backseat. safety arguments, calls for geopolitical competition, diffusion controls and much more might not be the drivers of the AI policy debate anymore; and they might not be the channels to which latent popular will for AI regulation runs. Whatever your pet issue is: The chances that it’ll get a headline, a prominent question or congressional intiative will suffer. I suspect there’s many viable takes on whom this will ultimately favour, but the following seems noteworthy and yet undernoted: whether you work on risks, races or reinforcement learning, you better get ready to answer ‘but what does that mean in terms of jobs?’.

The second part of this post takes a look at two examples of political coalitions that might be affected by that change: At the strategic crossroads ahead for AI safety advocates, and at a pain point for the accelerant ‘tech right’ coalition.

On Safety: Dig in or Disrupt?

AI safety advocates – the broad coalition pushing for safety-focused policy interventions ranging from stopping or slowing down AI development to liabilities for catastrophes to more stringent and enforceable evals for misuse and misalignment - are in a tough spot once a political shift like this one happens. For the safety coalition, there are some prima facie reasons to pursue any of three conflicting strategies: Allying with economic incumbents, allying with disruptors, or staying out of it. Of course, this movement is not monolithic, and I expect some organisations to take each of the paths laid out. But the movement is fairly interconnected and coordinated, and strategic consensus has a habit of forming relatively quickly, so I would expect a directional focus to emerge at some point.

Allying with incumbents

First, safety advocates could choose to ally with incumbents because it serves one somewhat popular safety-focused policy; the idea that a development slowdown might be advisable to catch up on important alignment research. There is some precedent for this – in the context of California’s SB-1047 bill, safety advocates sought the support of AI-affected incumbents like the powerful SAG-AFTRA union. That might sound like good politics: If you expect the incumbent faction to enjoy substantial support and ride a wave of backlash against the current tech-affiliated government, you might aim to introduce your policy issues to their platform through early coalition-building. On the very same token of politicisation, that move also exposes the safety platform to some risk – it makes pitching safety policy as an element of a disruptive and fundamentally pro-technology to any of the tech right officials like AI Czar David Sacks much harder.

Allying with disruptors

Second, safety advocates could instead ally with disruptors if they see the fundamental conflict lines between those that believe in AI’s transformative potential (and might disagree on how to make it go well) on the one hand, and those that seek to stop it on the other hand. A lot of the AI safety movement is convinced that an AGI-powered utopia is quite possible; they just disagree with the accelerators about how easy it is to fall down the chasm off the wayside. There’s also strategic incentive to ally with disruptors, i.e. in catering to the currently ascendant faction. If safety policy can brand itself as ultimately consistent with the ‘tech right’ policy platform, it might not need bigger political victories. This might be the thinking behind high hopes in the influence of the reportedly safety-focused Elon Musk, in the close reading of old tweets by David Sacks, and the broader notion of some safety advocates to learn to ‘speak Republican’. Of course, this risks exposure to the very backlash that Plan A (‘ally with incumbents’) wants to ride: If anti-AI sentiment driven by galvanisation of incumbent worries sweeps the political tables, new governments’ backlash could quickly extend to the safety agenda as well.

Staying out of it

Safety advocates might be tempted to ‘stay out of it’: Pitch their ideas on their own merit to decision makers on both sides of the debate, frame vaguely compatible, but largely technocratic policy to whomever wants to listen, but enter no closer alliances around party politics or omnibus legislation. That of course reduces the backlash risks above and might have the merit of ‘playing both sides’, but it can backfire for different reasons:

First, it risks reduced political salience. If a measure cannot be pitched to either side of the debate as closely connected to their respective policy goals and political mandate, then no one might be willing to put up the price or bear the political (opportunity) cost: If you think AI safety is a big policy priority, you might not want it to be a political afterthought. This is especially true because a lot of safety-focused regulatory proposals are quite politically costly: Moves like slowdowns to development, large international organisations, costly research projects or big-ticket foreign policy concessions are not likely to be passed in backrooms on technocratic consensus. If any of this is to happen, it needs political support; and to gather that support, safety policy might have no choice but to interface with the AI politics of the day.

And second, this strategy is vulnerable to defections: Single safety organisations might see political potential in defecting from a consensus of ‘staying out of it’ for short-term gain in a way that makes the broader advocacy platform vulnerable to mischaracterization: Once political adversaries can point to some examples of partisan alignment either way, the opposing political party might no longer believe the ‘technocratic’ pitch, and – presumably mostly unavoidable – small defections will have hurt the broader platform.

Deeper considerations around which directional focus should emerge are best discussed elsewhere; here, I simply aim to say: Labor market impacts pose a tricky political alignment question to safety advocates, and none of the available answers are without exposure risks. But coalition disruptions from labour market impacts don’t stop at safety advocates, either:

On the Right: Economic Populism or Technological Progress

On the right, and particularly within the current US government, happenstance has given rise to a coalition favouring racing toward more and more advanced AI capabilities. That coalition includes Donald Trump’s MAGA coalition, assembled i.a. around some economic populist banners, as well as the ‘tech right’ – technology executives like Elon Musk or White House AI Czar David Sacks driven by disillusionment of and antagonisation by the left as well as the pursuit of Republican political support and deregulation. With that coalition in power, many observers see a clear path to political support of AI development: ‘AI-pilled’ senior officials, a hawkish attitude toward China and low sensitivity to the protestations of civil society organisations seem like strong tails winds.

I believe that coalition’s incidental alignment is at risk once AI automation starts incurring costs to the electorate. Some observers already picked up on that tension at the occasion of the White House press conference announcing Stargate, $500b of private compute investment by OpenAI, Softbank and Oracle: When asked about labor market impacts, US president Trump expressed his optimism in Stargate creating US jobs – because he is a politician that has thrice ran on a platform and promise of high employment and growth. But while Sam Altman of course did not disagree ‘on stage’, it’s well known that he sees a different future: one that is sufficiently disruptive to human employment as to motivate new social contracts and a transition to universal basic income. That disagreement has the potential to split the tech right and MAGA coalition: They incidentally align on AI right now because its effects are still hidden in fog of war; but once AI labor market effects manifest, disagreement might break out.

On the one hand, the MAGA faction’s electoral incentives pull very clearly against enabling AI-driven displacement. In general terms, no politician wants to preside over job losses. But even specifically, the 2016 and 2024 Trump victories were predicated not only on a vague vibe shift, but on very clear perceptions of economic policy: The electorate thought economic issues were important, cared about keeping their jobs and being able to afford products, thought Trump was more competent on these issues, and hence voted Trump. If the current government now presided over substantial job losses and resulting economic worries, the incumbent coalition would be stripped of the most concrete building block of its recent victories. On the other hand, large parts of the pro-AI faction are very committed to not slowing down AI, to the extent that they consider slow-downs not only somewhat counterproductive, but actively unconscionable. On a sufficiently strong view of the likely benefits of hastening AI development and deployment, and a related strong view on how threatening a Chinese ‘AI race victory’ might be, economic incumbents would not be a valuable electoral faction to be accommodated as much as they would be a threatening obstacle to be overcome at full speed.

There has been a surprisingly informative ‘test run’ of that upcoming debate: Last December, debate along the described fronts broke out over the H1-B visa program, with the MAGA faction and auxiliary organisations like ‘US Tech Workers’ arguing for labor market protectionism against highly skilled immigrants, and the tech right arguing for the competitiveness and productivity boosts from hiring the world’s best and brightest. I don’t mean to stretch any analogy any further – what’s interesting here is the approach to trade-offs: Large parts of the MAGA right were quite happy to incur costs to growth and competitiveness in favour of catering to electoral concerns around employability and anti-migration sentiment, while the tech right was happy to compromise on conservative electoral incentives in favour of what they perceived as a substantive component of their business model. In that brief round, the tech right’s view somewhat prevailed, but I don’t think the matter is truly settled – see for instance the deposition of Vivek Ramaswamy or repeated lingering disagreements around how to treat the touchy subject of non-citizen workers – there is no stable consensus. Things might be much worse still in the significantly more impactful case of AI labor market effects. The current political coalition driving the ramp-up in US AI capabilities might not be built to last – counting on it could be costly.

What’s Next?

The upcoming labor market impacts from widespread deployment of AI agents create a volatile political climate. Two incidental coalitions relating to frontier AI policy face strategic crossroads: Safety advocates might decide to join one camp or another, and the tech right coalition is coming up on a wedge. No matter how the resulting realignments will shake out, frontier AI policy people of all stripes should be well aware of the impending terrain shifts in the arena of AI politics.

Since I’ve made that point, Zvi Mowshowitz has voiced some criticism, arguing that we currently don’t see much opposition to ongoing automation in software development. I think we just disagree on the level of required capabilities here: Cursor + top-tier models are impressive technology, but there is very little real labor market data to support the idea that they already have displacing effects. I think it’s only going to be systems like the next generations of Deep Research and Operator that will be sufficiently superior to many humans that adoption goes quickly. Zvi has also argued that all this doesn’t matter much because the scale of AGI and ASI is much larger than everything I discuss in that last post, and presumably, in this post. I think that view is dangerously mistaken: By talking about politics, I don’t mean to imply that the primary challenge associated with AGI is political effects; I mean to argue that the politics will play a large role in determining which policy interventions are feasible, what development speed and shape is likely, and thereby ultimately what kind of post-AGI future we’re heading towards. Even on a maximalist view of an impending singularity, I think this political contingency matters a great deal. So back to labor market politics.