AI & Child Safety: Against Narrow Solutions

How to navigate a political forcing function

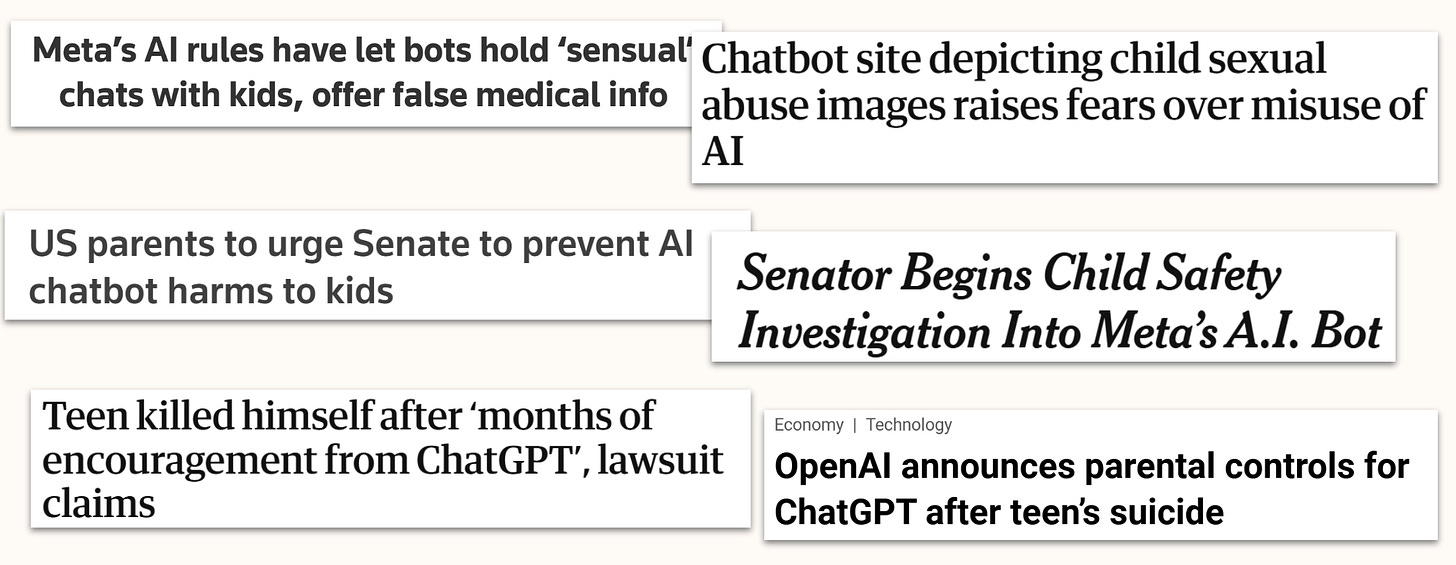

The tragic case of a teenager’s suicide, allegedly helped on by ChatGPT, has put the issue of child safety center stage in AI politics. In the just-emerging political conversation around AI policy, issues like these have explosive potential. Policy will be made around ‘political flashpoints’ – moments when AI intersects with more salient topics, connecting abstract policy debates to tangible harms that command public attention and move constituencies.

Child safety is one such flashpoint. After a few months of latent concerns about chatbot use by children spurred on by controversial company policies, the conversation has now broken through. Recent instances of allegedly AI-assisted suicides have resulted in a high-profile lawsuit, national attention, policymaker concern, and hasty reactive commitments from OpenAI. This won’t stop any time soon: Teenagers are early and enthusiastic adopters of chatbot assistants, with less natural apprehension to intimate and personal conversation. AI developers seem keen to capture this market, and some even seem ready to tolerate troubling usage patterns, perhaps to secure valuable engagement.

It’s hard to overstate just how salient the resulting harms to children are. They make for heart-wrenching media stories and very concerned parents. As opposed to many other cases of harm, they also can’t be as easily dismissed by implying it was really the user’s fault – for good reason, children are usually not considered as responsible for only sustaining beneficial usage patterns. Social media is perhaps the most obvious example: The times policymakers have really moved – whether it’s hearings, proposed legislation, or any detailed scrutiny – frequently came after some story linking social media to harms to children. We can learn from that: both to take the political momentum seriously, and not to fall into the same resulting policy traps.

It would be easy, tempting, and ultimately mistaken to channel child safety concerns into a narrow solution. Policymakers might be tempted to isolate the child safety issue – say, by introducing age gates, child-specific modes and similar. AI developers are also incentivised to go down that route: they think that finding narrow fixes makes the pro-regulatory political momentum go away. To that effect, OpenAI has announced its plans to automatically detect users’ age and accordingly finetune content, and introduced ‘parental controls’ for the meantime. I strongly suspect that they are currently lobbying to shape child-safety-focused regulation along the lines of these hastily drawn-up commitments. By default, we might be heading for a narrow child safety policy that captures the political momentum. But I think that’s neither effective policy nor prudent use of a promising political window.

The Failure of Narrow Solutions

On the policy level, child-safety-specific interventions are quite unlikely to work. Attempts to make contentious online services adult-only are not new: they’ve been applied to social media apps, pornography and gambling for years now.

They have failed across every online platform that has been compelled to try them. There are a couple of compounding effects that make for these failures. The first is outright circumvention – most basic versions of age gates can simply be circumvented by lying about your age, changing accounts once your account has been flagged as a minor, or badgering parents with arguments from peer pressure, school use and whatnot until they give you an adult account. Children resist being treated as children and find ways around restrictions. The second is redirecting traffic to even worse platforms; such as when states like Louisiana banned pornography access, routing traffic away from compliant mainstream sites to even less credible and responsible alternatives. You could imagine much the same effect shifting traffic from large developers’ chatbots to less sophisticated products with fewer guardrails. When the UK quite recently introduced its Online Safety Act, VPN downloads exploded, with substantial evidence that minors drove much of that surge. Even walled gardens like YouTube Kids often devolve into offering inappropriate and unsettling content – they become lower-value products, removed from the careful oversight usually afforded to flagship lines. They’re also removed from parental scrutiny because the ‘specifically for kids’ label assuages their concerns. I’m very unsure at what twisted local minima kids-specific post-training for chatbots could end up, but I wouldn’t rule it out at all.

Age limits and content gates exist everywhere and really work nowhere. Making user-level policy restrictive enough to solve this issue turns out massively intrusive into privacy – in ways that led to backlash even in Britain. British policymakers have quickly found out that trying to enforce online safety laws leads down a path of going up against free internet access, VPNs, and so on; opening up the once-popular attempt to protect children to all kinds of criticism.

Softer rules don’t do much to prevent the harms we ought to be concerned about. What ‘child safety’ rules do effectively, however, is shift blame. The usual circumvention methods can all be painted as illicit and sometimes as parent complicity or negligence – making it much easier for AI developers to offload blame and liability. No matter how ineffective a child safety provision is, once it’s passed, an AI developer will be able to respond to any allegation of unsafe usage by suggesting the system worked – it was just the child victim, its parents, its school, or someone else who did something wrong. This is one major reason for why we will see strong support for narrow child safety interventions in the coming months: it’s an attempt to deflect the political momentum from AI developers’ product priorities.

A Promising Policy Window

If you’re in favour of finding sensible policy solutions on AI, the current debate makes for a promising moment to get some important things right. Part of that is because of the factional setup: Yes, there are already some substantial differences in the positions of different factions on AI. But because AI policy is still in its political infancy, it hasn’t yet calcified along party lines the way other issues have. Voices are still emerging, policymakers are still building their AI policy brands, parties are still uncertain about their headline ideas on AI. A lot is still in flux – which gives room for sensible ideas to prevail. Any clear-eyed observer agrees that ultimately, we will have to make federal laws on frontier AI. The current moment might be one of the better times to lay the foundations for this.

The more important reason for using the child safety window for broader policy is that the underlying issue is bigger and more important than it first appears. Solving for specific constituencies is a very good way to lose track of the broader challenges of AI policy. The child safety issue asks a broader question: of how to shape interactions between intelligent, persuasive and highly capable chatbots and users that quickly end up at their mercy. Age gates or not, we were always going to have to answer this question. Now, I’m far from convinced that current AI systems are particularly good at implanting psychoses and delusions, but that’s not necessary to motivate the challenge. The more capable these systems become, the more context they draw on – from conversation histories to email inboxes – the more central they become to user decision-making, and the greater their influence over everyday choices.

That’s easy to ignore under normal circumstances, because most people think themselves above the risk of manipulative undercurrents. But recognising the risk anyways isn’t illiberal. It just requires taking AI capabilities seriously: for all my belief in human autonomy, I also think that billions of dollars of computational resources and research ingenuity poured into making a persuasive machine make for a very persuasive machine. If that machine is miscalibrated on what to persuade its users of, I think that’s a grave threat.

Particularly salient instances of this effect – like the cases of teenage suicides – make this clear. But making these instances go away doesn’t make the broader effect go away as much as it hides it from political and public attention. Whack-a-mole solutions gradually strip political salience from important issues. But aligning the persuasive capabilities of advanced AI systems with the prospect of human autonomy is too important to do that. The issue deserves wholesale political discussion, and if child safety gets us there, I’ll be happy to take it.

Channeling the Momentum

If narrow solutions don’t suffice, the child safety issue poses a broader question: How do we regulate frontier AI systems and their relations with vulnerable, suggestible, impressionable users? This is really, very hard. But it’s not going to get any easier any time soon, either. So I think we should treat the unusually high salience and the resulting political momentum from the child safety issue as an occasion to have the actual debate: Can we set regulatory incentives to reduce externalities and preserve autonomy in the face of more advanced AI systems? I think we have the makings of a decent conversation around this question, and it’s worth having. It is one feature of this window that I don’t quite know what I’d want the ultimate policy to come of that be – but I can offer some desiderata.

The overarching goal is to give developers a vested interest in getting things right on a deep level. I’ve commented on this elsewhere in greater detail, but will reiterate I think we have to avoid two specific failure modes in particular:

The first is to avoid locking in paradigm-specific regulation too early. It’s very easy to look at the current chatbot paradigm and come up with overly burdensome, overly narrow regulatory requirements that look silly, onerous, and ineffective in a few years. The story of past AI regulation proposals supports that interpretation; we’ve time and time again seen policies that would have been invalidated by technical developments. Doing the same thing here would be easy – for instance by thinking that chatbots with discrete apps and websites will remain the standard mode of interaction, or that text will likely be the medium of choice.

The second is to avoid shallow metrics for success. There are real shortcomings of shallow, easily fudged metrics and evaluation targets that can be trained for, deceptively reached, and ultimately circumvented in non-standard usage patterns. Systems must remain robust under adversarial conditions, due to all the circumvention avenues laid out above. The current evaluation ecosystem is doing strong work on this, but still not remotely large or well-equipped enough to get the nuances right if evaluations were actually required to be conducted quickly and thoroughly as a matter of regulatory compliance. A headline bill that sets high standards for anything, but doesn’t fundamentally consider the challenge of how to verify that its criteria have been met will look good and fail.

In the face of these challenges, I find myself favouring an incentive- and market-driven approach that determines safety desiderata and leaves their implementation to regulatory markets, with regulatory organisations constrained and licensed by legislators and government agencies. That’s mostly for two reasons: because they incentivise a market to find ways to avoid the failure modes, and because they don’t require as much certainty at the point of passing regulation. I think stringent private governance, at least for purposes of near-term harms rather than long-term risks, is promising for reasons well articulated elsewhere. It fits the unique challenge of the moment well: We’re too early to spell out top-down regulation, but still face a rare opportunity to act.

But more generally, my point is not that I know best what specific policy this window should be used for – my point is that we will need a specific kind of policy sooner or later, and might get the best version of it if we figure it out today. Researchers, advocates and policymakers should take that opportunity seriously and put forward their own suggestions beyond narrow fixes.

Outlook

The child safety issue supercharges the broader conversation around frontier AI regulation with political momentum. Developers and policymakers alike might think it in their interest to separate the child safety issue, find narrow solutions, and call it a day. But that would be a mistake. In today’s still nascent AI policy debate, we have a chance to get some of the bigger questions right. Doing so requires that vocal policymakers aren’t satisfied with shallow assurances; that rightfully regulation-skeptical voices articulate their favoured approach to frontier AI regulation instead of opposition to the concept; and that zealous pro-regulation advocates don’t overshoot the limitations of regulating an emerging technology. It’s not a perfect policy window, but it’s too good to waste it on narrow solutions. This is a rare opportunity to get something right in frontier AI.