The AI Takeoff Political Economy

If AI policy does not get ahead of its treacherous politics, this revolution will eat its children.

Nuclear power is pretty impressive technology — that much was clear in the mid-fifties, when, following Dwight Eisenhower’s ‘Atoms-for-Peace’ speech, civilian reactors in the US and USSR were first connected to the grid. I suspect it would have been quite surprising to the scientists at Oak Ridge or Obninsk, had they been told of the rocky road ahead for nuclear power: of the political idiosyncrasies that would keep it from even broader adoption, the security lapses, the regulatory slowdowns that’d cause the technology to stagnate, and its ultimately small share of 2025’s energy mix. Politics has been astonishingly unkind to nuclear power. This observation is a well-established launching pad for hot take; here’s another one: The most important work in 1955 energy policy would have been getting ahead of the curve on nuclear power politics. Today’s situation in AI policy is similar — on a much greater scale.

From here on out, AGI is quite conceivably a mere engineering problem. If you talk to people at the labs, most tell you the same thing: All the pieces are in place; between ~working agent scaffoldings, multiple scaling avenues through pre-training, inference, and possibly synthetic data production. A slow consensus is forming around that observation: One of the leading US labs might build AGI this decade, and it might not kill us all. The clearer the technical path seems to emerge, the more the certainty around these predictions grows – but while the science is starting to settle, the politics are starting to stir.

I feel that the path ahead is a lot more politically treacherous than most observers give it credit for. There’s good work on what it means for the narrow field of AI policy – but as AI increases in impact and thereby mainstream salience, technocratic nuance will matter less, and factional realities of political economy will matter more and more. We need substantial changes to the political framing, coalition-building, and genuine policy planning around the ‘AGI transition’ – not (only) on narrow normative grounds. Otherwise, the chaos, volatility and conflict that can arise from messing up the political economy of the upcoming takeoff hurt everyone, whether you’re deal in risks, racing, or rapture. I look at three escalating levels ahead: the political economies of building AGI, intranational diffusion, and international proliferation.

The Politics of Building AGI Isn’t Settled Yet

Political support matters a lot for how a takeoff might go; variables range from the extent of public-private partnerships, licensing and permitting support for datacenters and their energy supply, coordination of private investment, extent of securitized state-run projects, and policy approaches to the trade-off between risks and racing. With the ‘tech right’ politically ascendant and the idea of the ‘AI race’ arriving in DC, it seems government is off to the AGI races. As a result, we see a lot of hasty alignment with the right and a lot of confidence in an enduring political mandate. I think that might be misplaced: Political support for the current AGI trajectory can crumble and ultimately backfire. That’s not only a problem for AGI optimists: the muddier the politics get, the worse the chances for sound policy of any flavour.

There Are No Permanent Majorities

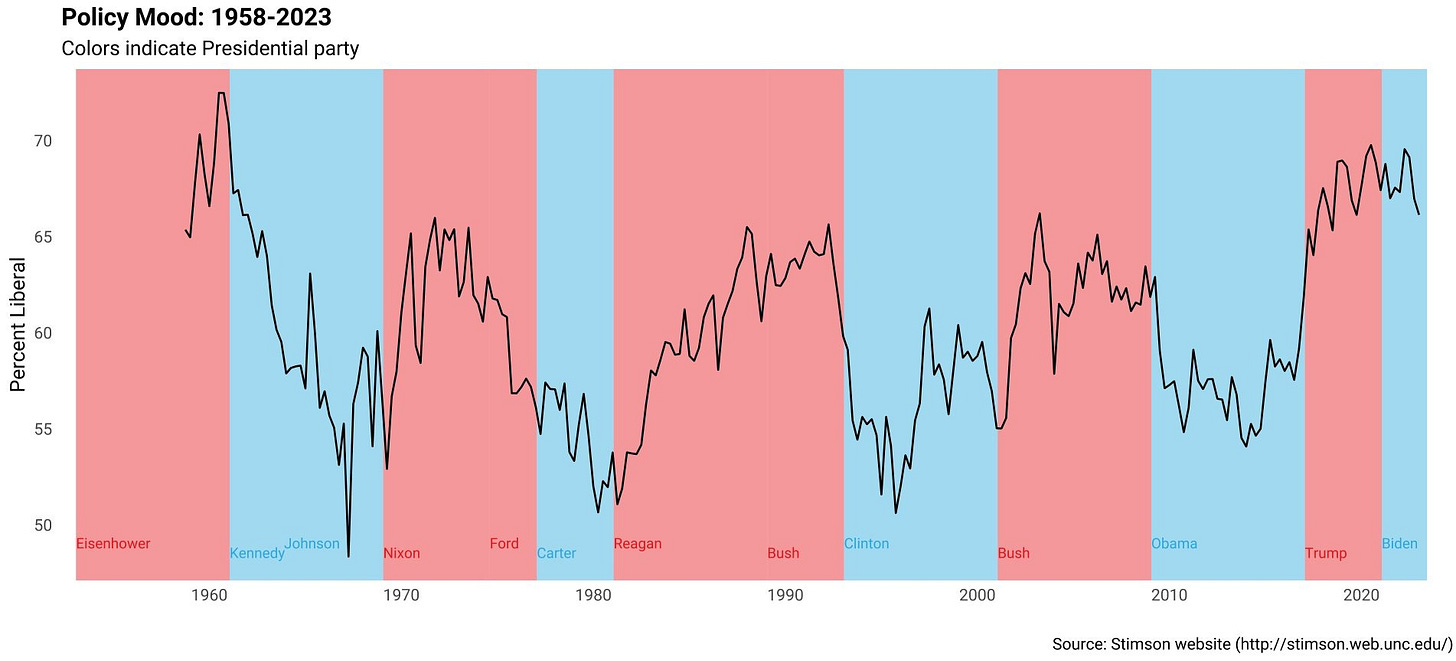

First, political vibes can shift back pretty quickly, and when they do, they do it with a vengeance. AI itself is still a somewhat niche topic, but as the tech elite has quite publicly allied with one political party now, AI policy has grown more and more susceptible to the repercussions of changing political tides: When democrats come back with a perceived mandate of rolling back recent republican action, support for building AI will be on the chopping block. Whether through midterms, resistance-coded state legislation, or a democrat victory in 2028: Vengefully strict regulation on tech, reflexive rolling back of executive orders, post-midterm legislative blockades could be coming sooner than expected. This is especially true in the broader context of a democratic party struggling to (re-)assemble a coalition: As I argue further below, fear of displacement and change from AI could be a powerful rallying point to assemble a counter-vibe-shift around. And then, who’s to say where the politics go from there?

Some of that is unavoidable – somewhere on the road to AI takeoff, the issue was going to reach sufficient public salience for it to be politicized anyways. But it’s still worth noting how and when exactly it might happen. And there are ways for people in policy to accelerate or decelerate politicisation: The downside to the currently popular ‘learning how to speak Republican’ is that you start to sound Republican to Democrats, too (and vice versa, of course). That might not feel like much of a cost as long as you’re riding the political wave, but it can make your agenda slip out of your hands in the inevitable backlash. Reckless politicisation is not conducive to sound policy that corresponds to any part of the rapidly-moving frontier of potential, risk, and capability. Right now, the AGI project seems dramatically overexposed to broader political risk.

Accidents Can Happen

Second, returning to the initial analogy to nuclear power, disasters change public support in a heartbeat. After Three Mile Island, nuclear power growth in the US stalled, and after Chernobyl, the soviets grew wary, too. Just as the US and China today, these were superpowers with a strong interest in the civilian and military applications of an objectively superior technology; but their political systems weren’t resilient to the paralysing effect of catastrophe, either. Plenty of strong research suggests that risks of serious harm are real; but there is a temptation to dismiss them, either from ardent accelerationism or China hawkishness. The political economy lens should motivate a different view: If you want political support for your flavour of AI takeoff, you really ought to be very concerned with preventing disasters.

And third, rising tensions and even armed conflict in the near future pose material, but also political risk. AI is slowly being treated as a somewhat strategic technology, but as far as anyone can tell, the kind of general-purpose models at the center of the AI takeoff story do not have a truly military dimension just yet. If an armed conflict – most notably, between the US and China – were to arise in the meantime, priorities could shift very quickly. Lots has been said about the non-political ramifications, from datacenter sabotage to supply chain disruption. But an imminent war matters on politics, too: Future securitised projects might quickly be deprioritized as the Pentagon scrambles for an immediate advantage, the economic policy agenda could be realigned to pivot to a war economy, and scarce energy supply might be reassigned.

Intranational Diffusion Is Treacherous Terrain

Let’s assume AGI systems successfully get built without the politics going awry. We are far from out of the woods then: Proliferating this sort of technology through an advanced economy is politically highly vulnerable. Bargains must be struck, assurances must be made and trust must be built far in advance.

Economic Incumbents Can Dig In

The most obvious flashpoint for turmoil is around incumbent economic interests. For two months last year, it looked like there was a path to port automation in the US – a policy so technocratically sane that it bordered on obvious. That hope quickly died when it clashed with a niche lobby of economic incumbents, the longshoremen union. Neither the global gains from potential automation, nor the fact that systemic rivals to the US have automated ports, nor the fact that you practically speaking don't need the longshoremen anymore once you’ve automated their ports was enough to get the idea across the finish line. And yet the case for AI displacement overcoming institutional barriers to labour market displacement hinges on very similar mechanisms: gains, geopolitical pressures, and rapidly falling influence of the displaced.

I figure there will be quite a lot of powerful AI longshoremen. Depending on the exact shape of the first ‘remote drop-in workers’, they could be anyone; currently, AI does best on coding and formulaic analytic and language tasks, threatening a lot of white-collar economic bedrock, including quite a lot of younger professionals that haven’t built more idiosyncratic skills that might retain demand. That exposes a pretty broad group to displacement and disruption – one that is richer, broader, much less localised and much more publicly visible than the longshoremen. Past automation diffusion was already a rough political fight, this will be a different foxhunt altogether. I believe that should make it pretty clear that AI diffusion is not something you can just do to people. If it is your belief that this ought to happen: for it to happen well, predictably, and efficiently, it ought to have some more substantial solace to offer to the displaced than vague, system-wide gains.

If You Change The World, People Will Get Scared

But entrenched interests do not even necessarily have to be directly economically incentivized to dig in deep. People are just often quite afraid of change. And a transition to an AGI-driven economy will strike many as fundamentally alien, and thereby threatening to their hopes, lives, and dreams. If there is one thing you should take away from the eschatological posting habits of those ‘in the know’, it’s that there’s a lot of ways to react to AI progress in emotionally and spiritually maximalist manners. How do you think people who haven’t spent the last ten years on AI will feel? AGI is an unfathomably impactful technological prospect, and the dread, worry and anguish will be to scale. To make that worse, the institutions that should alleviate that worry are not equipped to do so. Confidence and trust in the government and in tech corporations is very low, and they are doing very little to improve that, or to prepare society for the turmoil ahead. There are no effective ambassadors to reassure scared people at the edge of tomorrow.

Maybe the worries will be salient enough for an anti-AI coalition to emerge organically. If it doesn’t, these worries can easily be instrumentalized, attached to scapegoats and tangentially related demands of all flavours. I don’t know yet who will be in line to leverage that – but it’s worth noting that the democrats are scrambling for a new story, are negatively polarised against the tech ecosystem, and have a strong track record of playing to incumbent labour concerns. This is primarily about the broader point: Rapid AI progress creates latent political energy that can blow up in a number of ways, from slightly disgruntled incumbents to luddite revolution. The diffusion of AGI throughout a society faces a volatile political economy that could backfire against anyone. Even if you purely pursued smooth and fast AGI deployment at any cost, you would be much better served by a more considered approach that gives legitimate incumbent interests a real political outlet.

There Is No Plan For International Diffusion

The current default for international diffusion of AGI systems developed in either China or the US is quite restrictive and hence highly prone to conflict and chaos. Three diffusion barriers come to mind:

Nationally mandated limitations on the proliferation of privileged system features like model weights could be introduced in an attempt to secure frontier capabilities.

Already-existing barriers to the diffusion of compute might become both more stringent and more relevant as demand for inference compute increases.

On the military side, the incentives are even tougher: Great powers are likely to jealously guard their securitised frontier capabilities, sharing them only where necessary.

I’ve written before on what some middle powers might be able to do to prevent being left behind, and economic incentives could provide a partial fix, but there’s plenty of reason to doubt that the same old economic principles will carry through to a more AI-centric paradigm. By and large, global discrepancies seem like the default outcome. That makes things very volatile.

Trivially, many of the positive effects of AI scale with how many people will actually have access to that AI. If you look at the achingly slow global diffusion of many types of technological progress, simple trickle-down of technological progress should not be sufficient solace. This is a decidedly political problem: currently, the incentives pull toward a jagged edge of international diffusion. Smoothing it out through forward-looking work on equitable policy and politics before the fact might yield more marginal AGI person-years than further accelerating take-off.

Death Ground for the Rest of the World

Through this post’s lens of political economy, the even bigger issue is that the default version of AGI takeoff can look like a global zero-sum game. If there is no believable and believably communicated plan for the further development and deployment of advanced AI, a lot of people in a lot of countries will get very worried. They might perceive themselves as systematically threatened in the viability of their economic model, the stability of their strategic position, and the sustainability of their way of life. That usually makes for volatile geopolitics, and could drive radical action:

First, by governments, who might try to get on the disruption’s good side by selling out to great AI powers, in a rapid rollback of the multipolar international order. If that does not work, or they feel the threat is getting existential, they might decide to strike first in any number of ways, from sabotage and tariffs to all-out war. Especially if nations feel that an historical strategic adversary is about to gain a decisive advantage – e.g. because they will be given AGI by a great power –, a dozen uneasily pacified conflicts could reignite. This is what happened in 1914, when the German Empire, fearing the industrialization of the Russian military apparatus, willfully escalated tensions into an all-out ‘preventative war’, or 1967, when a ramp-up in Egyptian military capabilities motivated an Israeli first strike; and the incentives are set to be stronger still when talking about paradigm-shifting technology like truly advanced AI.

Second, by citizens: With low trust in institutions and few good policy options for many of the natural losers of an AI-powered paradigm, they might take matters into their own hands. Somewhat stable governments could fall at the hands of erratic movements of AI backlash: as fear and uncertainty mount, they can easily become flashpoints for destabilizing political movements and whatever pseudo-solution they might pitch. Alliances, supply chains and safe borders can quickly crumble. And if citizens give up on their governments’ ability to manage the transition altogether, mass migration to AGI nations might be a real option. If the transition shock is not carefully managed, it could readily ignite global chaos at a scale that will be felt even in the great AI powers.

No Solace from Superintelligence

Getting to ASI relatively fast does not insulate against the damage this transition phase could cause. Terrorist attacks and desperate supply chain disruptions can shake up things at any stage of AI takeoff. And if global institutions are disrupted and eroded through a period of fear and uncertainty, distribution channels for AGI benefits could be damaged for years to come, hindering post-AGI recovery substantially. Only on a very specific form of maximalist AI capabilities could simply building a system solve these issues. In a lot of grittier scenarios, it's the politics that matter.

Sometime soon, a large share of the world’s citizens and a major part of the global economy might think themselves on death ground. I think we’d rather not find out what this will make them do. Avoiding that requires making a good, believable plan for global diffusion and communicating it very well very fast. Most current policy on this still works in the opposite direction, restricting diffusion in the service of strategic interest. We’ll need to do much better than that.

Conclusion

No matter what aspect of frontier AI policy you work on, one of the most urgent questions should be how to navigate the impending broader political disruptions around the AI takeoff. That requires a much more serious look at a lot of questions that have seemed very abstract for very long – specifically around how the national and international diffusion of this technology will happen. On an issue this politically volatile, serious thinkers with serious ideas ought to get ahead of the conversation. Otherwise, the volatile political economy of the AI take-off will blow up in all our faces, and the revolution will eat its children.