Unbundling the AI Safety Pitch

A more institutionally and intellectually heterogeneous AI safety policy environment could take more chances and be less strategically vulnerable.

In last week’s post, I wrote about the shortcomings of the once-successful AI safety policy coalition in the politics of 2025. My main point was that the safety coalition had been very good at informing and influencing receptive policymakers, but is now much less suited to political fights that required real leverage. This post is about what a movement more able to win these fights might look like: more heterogeneous in terms of its policy focus and the structure of its institutions.

This movement-level need is well-illustrated by some of the ongoing and open strategic debates on how to advance safety policy: One compelling strategy might be to position well for upcoming times of increased political salience of AI safety, as it might result from a case of large-scale AI misuse. If you want ‘the safety movement’ to be well-equipped to capitalize on this, you want its broader politics to be above reproach to render it the port of call for policymakers and national security types once that misuse case rolls around. Another attractive strategy might be to create the political salience yourself by marrying the safety case to a broader political platform that’s powerful enough to take over the AI discussion and pass omnibus bills with mutually beneficial elements, e.g. by allying with displaced workers over politically salient job market disruptions.

It’s easy to see how goals like these are in tension. To interface successfully with a discontent labour movement, policy asks and public communications have to fit a certain vibe: believably conservative with respect to the makeup of the labor market, generally skeptical of technology, presumably aligned with broadly left-wing notions of restrictive labor policy. The very same orientation might disqualify safety advocates in the eyes of policymakers trying to prevent the next AI disaster; they’ll be wary about accidentally importing ‘left-wing decelerationist’ viewpoints in trying to increase public safety. How to respond to that bind? You could place a big bet on one play or the other; but that is risky. Or you could have parts of the movement do one thing, other parts the other, so you always come out on top. But for that to work, I believe, you’ll need a slightly different movement: one that is heterogeneous enough so that not nearly every safety advocate gets lumped in with every other safety advocate and exposes them to political risks.

My offer with this post is that safety advocates might get to have their cake and eat it, too. If the movement managed to diversify its policy foci, its external perception and its choices in institutional setup to an extent that would allow some safety advocates to make – for example – a decisive play for the tough-on-crime security pitch, and another entirely to make a play for the labor policy alliances, AI safety might move from being surrounded by constraints to being able to launch political initiatives in all directions.

A Brief Look Back

The origin story of the safety movement’s homogeneity, and the good reasons that motivated it, are better understood as path dependency from initially sound strategy than dunked on with the benefit of hindsight. The safety movement traces its origins back to a small group of people that began taking AI seriously when few others would. The intersection of the EA and rationalist communities came to believe that AI capabilities would grow quickly, could pose serious risks, and these risks ought to be addressed: through technical research, but increasingly also through policy work. This world view was sufficiently ‘out there’ in 2021 to provide for a homogeneous movement that was far more united in its idiosyncratic views on AI policy than divided in any other regard. With the support of very few initial funders – most notably Open Philanthropy and its corollaries, and for a time, FTX – and through very few initial talent pipelines – mostly from major anglosaxon universities, motivated by organisations like 80.000 hours, through a range of AI-safety-affiliated research institutions –, an AI safety policy ecosystem was scaled up.

This story is sometimes told in a sneering tone, as if to suggest doing so was somehow illicit. I do not think that is appropriate; I think this history is in large parts that of an astoundingly successful first chapter. But the centralised character of the early success story explains the homogeneity this piece gets at: The same funders, with the same ideas of what might be the hallmark of a good organisation, decided which organisations ought to be incubated. The same class of closely interconnected leadership of a highly intellectually deferent movement decided which ideas were worth pursuing and doubling down on. And successful blueprints for starting up organisations in one policy space, at one institution or in one jurisdiction were very efficiently copied and proliferated through the movement. As a result, the safety movement consists of a lot of different organisations with similar modi operandi and similar substantive policy views that go beyond the foundational descriptive assessment that ‘AI will be big and risky’.

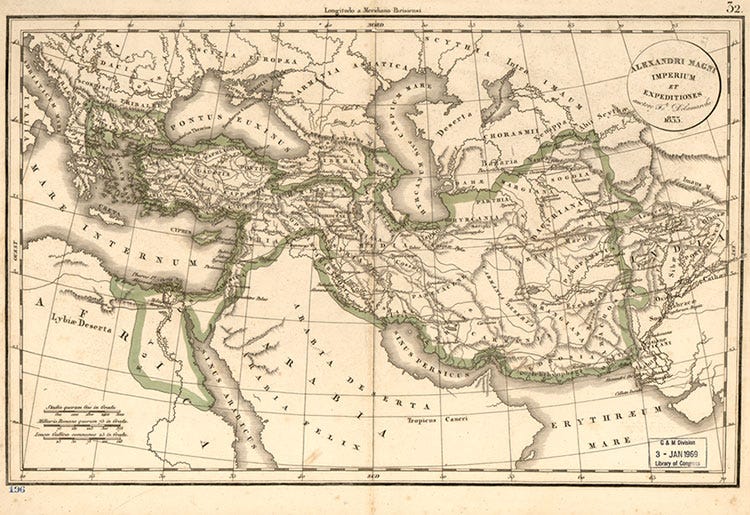

As AI reached increased political salience on the coattails of capability gains and economic interest, the AI policy space began to grow: new organisations, new stakeholders, new voices abound. At the start, it was unclear what this growth would mean for the incumbents that had exclusively occupied the realm of ‘taking AI seriously'. If you drew a map of the AI policy environment in its early days, it would mostly have included safetyist organisations. Once that landscape grew, two new maps were possible. An alternative world would have seen safetyist organisations scattered all over the spectrum; some among the left-wing, some among the right-wing orgs, some for a large role of the state, some for market supremacy, etc. That’s not what happened; instead, today’s map, both as measured by real ties and alliances and by outside perception, still has the safety organisations tightly clustered: Any safety organisation is much more similar to all other safety organisations than to any other set of organisations. Because of that, political and PR risks and benefits are collectivized among the cluster.

I think that should motivate a closer and more critical look at two related, highly contingent features of today’s safety landscape: A look at the substantial vertical integration of different kinds of policy work within single AI safety organisations, and a look at the lack of diversity in terms of policy platform and focus area between these organisations.

One Cause, Too Few Voices

A lot of safety policy organisations work on very similar things. Sure, you might say, they are safety orgs, so they’re bound to be working on similar stuff. But there is plenty of room under what should be the general safety banner of ‘these systems pose serious risks’: AI safety, broadly conceived, could be framed in a number of ways, from a distinctly Christian conservative pitch of conserving creation to a hard-left pitch of pushing against tech corporation supremacy. Sometimes, external communications lean into one of these pitches or another; but very rarely does it seem like a prominent safety organisation or its leadership really does approach AI policy from a notably idiosyncratic angle. AI safety also warrants itself to many distinct policy areas: you could well imagine some safety organisations exclusively concerned with AI agents, some with model development, some with security policy. Safety organisations do somewhat better on that front, but there are still very few highly specialised policy-area specific actors, and even fewer still that are both specific in terms of policy area and political leaning.

As a result, you’ll often see safety organisations acting in lockstep: If a policy or framing is favoured and adopted by part of the safety movement, it’s largely favoured and adopted by all of it. You won’t see much public disagreement, and you won’t see much plausible distancing. So if the idea turns out badly, so too, it falls back on the entire safety movement.

Even if you think that some more diversity does exist behind the scenes, and that there are some salient counterexamples: Much of the risk from this homogeneity stems from outsiders' perception of the safety movement as monolithic. If you think there’s substantial internal diversity, it nevertheless isn’t very visible from the outside, and certainly not to policymakers. That’s especially true if these policymakers are primed to perceive a monolithic movement as the result of adversarial framing. As far as I can tell, that’s not due to a lack of organisations, or a lack of funding, based on how many generalist AI safety policy organisations there are nowadays (no, I will not insert a chart of logos and acronyms). To be sure, there’s good discussions to be had about the merit of many of the specific framings I discuss, but all in all, it is remarkable how very similar a wide range of AI safety organisations comments on the same broad range of issues. This carcinisation has serious downsides. A more heterogeneous environment with a lot more specific local foci would have serious upsides.

Partisan Compatibility

First, heterogeneity leads to greater partisan compatibility. If some organisations are clearly and overtly Republican, they’ll be on the inside on political platforms, party strategy, congressional planning; stay on the callsheets of administration partisans and power brokers; and their members will be well-positioned for nominations to legislative office or executive appointments in ways that a simply bipartisan organisation could never provide. That ensures that some version of the foundational policy assessment persists through political shifts, and it increases the chances of finding more permanent purchase beyond incidental policy initiatives. Right now, there are very few AI safety policy organisations that any party, or even party wing, considers distinctly ‘on their team’ as opposed to incidentally aligned. Much potential is lost here.

National Compatibility

Second, it also leads to greater national compatibility in times where AI policy shifts to discussions where national loyalties matter. If you are to advise policy around securitised AI, you ought to be able to sell governments on the idea that you’re on their team. See, for one salient example, the instance of GovAI’s policy work leaving them open to attacks by US Senator Cruz painting them as foreign agents.The same thing is, more subtly, happening in Europe, where policymakers are highly skeptical of how well-intentioned US policy organisations, especially around national security, might really be. The soft movement consensus to focus on US policy has somewhat remedied this by motivating believable concentration on the US, but should that ever change, I’d expect this problem to return.

Enabling Moonshots

Third, more generally, diversification enables single organisations to take much greater political risks. For instance, single organisations might do well to enter early alliances with politically highly disagreeable groups or people. In hindsight, starting a MAGA AI safety org in 2023 doesn’t look too bad; in foresight, a lot of people are starting to feel like they should be early to allying with unions and displaceable workers. Organisations might also want to go all-in on a very specific piece of framing or content: start warning about antisocial effects of agent proliferation, or specifically cyberattack risks from advanced systems, or whatever else, now. Then, if that issue becomes big, they can point at their history of having been correct about this and will be the first port of call for policymakers that want to get up to speed. That’s particularly promising in AI policy, where progress is moving fast, and being right about it is a token that appreciates value quickly. But there’s downside risks to moonshot strategies: If Trump loses the election, you’ll suffer the political backlash; if cyberattacks turn out to be much more harmless than you thought, you lose credibility (to some minds, this has already happened with bio risks and 2023-era advocacy!).

Right now, single safety organisations cannot take these risks, because they are collectivized across the movement at large. Failures and political actions of single safety organisations fall back on the entire safety environment, specifically because they primarily appear as safety organisations from the outside. The climate movement is instructive in both directions on this issue. When there are extreme climate protests, like those by Extinction Rebellion and its local subsidiaries, some primarily-climate-focused organisations get hit with political backlash; but some, that have found a well-defined focus that meaningfully diverges from ‘caring about climate’, don’t. Now the actions by Extinction Rebellion seem provably counterproductive, but a lot of ex-ante promising political moves will look almost as bad in hindsight if the shift of winds they bet the house on doesn’t happen after all. I’d even argue that going all out on SB1047 is an example of how this happens: Some orgs followed the moonshot of getting actual frontier regulation past a pro-tech party establishment, and when that backfired, most safety organisations got caught in the blast. To enable making this sort of play in the future without endangering the broader idea of safety policy, the movement could insulate the rest of its organisations through believable diversification.

Existential Risk Insurance

Fourth and relatedly, greater diversification of content and messaging insures the safety movement against political risks. This is not limited backfiring concerns; even a measured and conservative strategy can sometimes take serious damage, through a personal scandal, an idiosyncratic disagreement with some political leadership, a really bad piece of policy, etc. The less the ‘safety movement’ appears monolithic from the outside, the less it can fall victim to this kind of systemic risk. The more a local risk can be contained by pointing at its victim and arguing ‘no, they have nothing to do with this - these are the left-wing safetyists, and here’s 19 counts of us disagreeing with them’, the less it threatens to prove existential to the overall movement. Right now, safety organisations are too interlinked to do that.

The Failures of the Full-Stack Approach

AI safety organisations do not only hold similar positions; they also go about advocating for them in very similar ways. Currently, a lot of organisations that do policy work on safety follow the same blueprint. They do semi-scientific research, public comms around that, and then talk to policymakers on that basis. This integrates four distinct modes of working to affect policy: Communicating external, neutral expert opinion, developing and researching policy, and advocating for specific policies through both policymaker outreach and public communications. For each of these four modes of policy work, integration with the other three carries some risks, many of which have manifested in the last years of safety policy work. Three salient examples come to mind:

Insulating Expert Consensus

First, one commonly integrated aspect of safety policy is communicating a purported scientific minimal consensus. This usually means consolidating claims of leading scientists, such as from the progenitors of deep learning, and minimal suggestions that near-necessarily follow from them – this is comparable, for instance, to the work the IPCC is supposed to do. But this function is endangered when top-level expertise is closely integrated with more contentious forms of policy advocacy, because the air of neutrality is threatened. The hope behind that integration is that, by association with the impeccable credentials of its figureheads, a policy movement can present itself as the voice of the experts.

In effect, what happens just as often is that the more contentious ideas of advocacy organisations are associated with the top-level experts, and that is used to call their expertise into question. In AI policy, these experts are often closely affiliated with policy organisations: through close collaboration, proliferation of the relevant statements, funding, etc. As a result, it has become easy and well-practiced for political adversaries of the AI safety movement to cast the leading safetyist experts as biased doomers pushing one policy pitch as opposed to neutral authorities defining the policy window. Maybe that’s unavoidable to some extent, but I think it’s unwise to characterise bad-faith attacks as an immovable given: There are ways to minimise surface areas, and there are ways to expose yourself to attacks instead. Keeping the boundary between neutral experts and opinionated advocates unclear is the latter.

Unshackling Public-facing Work

Second, public outreach and communications should be able to make outrageous claims and throw rocks at the overton window – especially where it aims to mobilize a broad movement, create political salience through outrage and emotionalisation, Doing that often has real costs to more serious political credibility: a policymaker that just got done scraping off the orange paint off their fur coat will not be particularly enthusiastic to meet with Stop Fur Coats Now, or to invite them to their next advisory group. Similarly, for some flavours of an effective safety movement, you might want to enable serious, determined organisations to throw orange paint or write op-eds proclaiming that policymakers are playing Russian Roulette with the world, but simultaneously keep a strong in to provide expert advice and capitalize on the political landscape that is shaped by movement building. This is much easier if there is greater intra-movement organisational diversity. The current set-up means that this kind of public advocacy is mostly done ineffectively by small, peripheral fringe organisations, while funding, competency and strategical considerations flows to the full stack organisations that fail to shape a broader public environment.

Research Neutrality and Advocacy Polemics

Third, there's potential anti-synergy between policy research and political advocacy in general. For a similar reason to the expert advocacy argument, policy research often benefits from an air of neutrality. The policy outputs researchers create are supposed to be compatible with many platforms, their findings are supposed to be taken seriously on both sides of the aisle. And the leadership of research organisations is often most influential where it can be cast in influential technocratic roles – but these roles are often much harder to attain if the selectors have to fear backlash from fear of making a partisan or otherwise contentious choice.

But political advocacy sometimes might want to be partisan and contentious. It’s often effective for policy advocates to be able to be polarising, partisan, highly opinionated in a way that is entirely inappropriate for neutral research organisations, in hopes to resonate better with policymakers, offer them political cover for heeding their advice and exacting their suggestions, and to positon and entrench themselves better within political alliances. This current tension keeps many AI safety policy advocates from more aggressive messaging, and raises real credibility costs for many AI safety policy researchers.

On that last point, readers might note that this setup is not unprecendetd; a rich tradition, particularly of US thinktanks, does well on the research and advocacy (‘think-and-do-tank’) model. I believe that this integrated model is valuable on three occasions, neither of which we find ourselves in:

First, when there’s the need to raise awareness in an unpoliticized field; I believe that’s part of why safety organisations had such a strong part when no one knew about AI.

Second, a clear need for policy solutions against the backdrop of a political consensus – like in the RAND glory years, where it filled in the technical gap for a bipartisan agenda of strategic and technical supremacy.

Or third, when there’s an ecosystem-internal need for policy ideas, debate & ammunition, for instance within political parties or movements. This is what many well-established partisan thinktanks, from Cato on the US right to the Fabian Society on the UK left, do well: They form the intellectual backbone and industrial idea capacity for their broader political hosts.

The first two occasions don’t describe the current political environment well. The third occasion could apply, but as I argued above, AI safety organisations’ lack of (perceived) political distinctiveness hurts their pitch. For the time being, it’s a tough time for vertically integrated policy organisations in AI safety policy.

What Could Be Done?

So what’s next? Some ideas I already interspersed throughout. I’ll summarize them as a quickfire overview:

Diversify organisational focus – ensure a greater share of mono-strategy organisations, e.g. those that chiefly focus on policy research and refrain from advocacy, focus on expert consensus and refrain from more contentious suggestions, pursue public advocacy and leave the policymaker engagement to others.

Have organisations seek niches and moonshots, such as in terms of political framings and coalition building. As a corollary, don’t mind the gap: It’s fine if most AI safety organisations don’t have something to say on most AI-related issues.

Disambiguate the safety movement through sometimes costly, visible signals. It’s good if safety organisations sometimes disagree with legislation and framing advanced by ‘fellow’ safety advocates. A public-facing, controversial, political intra-movement debate is not something to be avoided for fear of providing ammunition that will be manufactured anyways, but one of the few ways to buy credibility.

Don’t approach all this as a matter of Machiavellian cleverness and pretense. I’m not saying the safety movement should act as if they did the above. This is rarely effective, and even more rarely believable. Doing this requires the genuine empowerment of new ideas and strategic directions.

Would the movement that followed these recommendations be a bit less of a unified front, a little bit less homogeneous? Certainly. But at this point, I am not 100% sure whether the depth of integration and strategic coordination has done particularly well. It’s a gloomy time for AI safety policy, and maybe minds will shift back on this – but for now, I would not be eager to describe this as a running system that oughtn’t be changed.

What to Do About Funding?

The elephant in the room behind these suggestions is funding diversification. A lot of commentary laments the outsized influence of the few active funding sources. And I think it’s entirely possible that this influence contributes to a lot of the homogenisation trends I described. But you can’t just choose to diversify funding ex cathedra - it just happens that for many organisations, it’s getting funding from these few sources or not getting any. Diversification has, in fact, been a long-standing goal, but it hasn’t been too successful.

I believe what I suggest could help with it: The funding system for an organisation that presents and networks as a safety organisation is narrow, and so reliance on the few available sources remains. The funding system for partisan organisations, or organisations that plausibly present as being specifically about a more narrow policy area – security, labor, you name it – is much larger and more diverse. If safety organisations intersperse across the political spectrum, they also intersperse across funding sources, in a way that could counteract homogenizing forces and solidify its diversification. They just need a little push to start.

Outlook

There’s plenty of good AI policy, and plenty of valid strategies to achieve it, that could well be worth considering. But the homogeneous structure of the AI safety policy ecosystem collectivizes risks both within organisations and across the movement. A more heterogeneous movement that seeks niches and spreads out across the political spectrum would be much more able to seize future political opportunities.